In my view, in fisheries, there are way more “opinionholders” than “stakeholders”, which, interestingly, at least from what I can see, is the opposite of land-based primary production like agriculture, dairy, and forestry, for example. You read tons of news analysing fisheries issues, and very few on land-based, which, as I discussed before, is substantially more impactful.

In a similar vein, I see way more analysis in the news and academic papers on the EU Fisheries Access Agreements with other countries than on those from all the other Distant Water Fishing Nations (DWFN), even though all of them have access agreements.

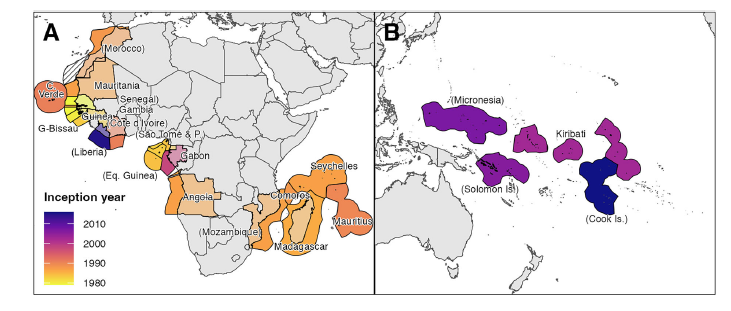

Map of the network of fishing access agreements developed by the EU around Africa (A) and in the Pacific Ocean (B). Chances are you could not find the text and details of all these agreements for any other DWFN.

I think this “more attention” to the EU ones comes from the fact that the EU upholds higher standards than the rest of the DWFN, but also from its transparency….For a copy with all the details for each EU agreement, you just need to go to a webpage and download them. Yet for the ones for. CN, TW, and KR, for example, chances are you need to know people in really high places, and even so… you may not see all the details.

And as much as I have criticised many of the technical issues around EU Market Access, I have always been very upfront in recognising that it's all above board, you have open access to all documents… and, fundamentally, they have always funded capacity building activities not only for the countries they have agreements with but also for many others that they don’t… and that sepatates from other resource users + donors combo as the DWFN are.

Chances are that a paper like this one could not be written about the fisheries agreements of any of the other DWFN, simply because the information would not be available… simply as that. So whatever your opinion is about the EU fisheries agreements, you have to recognise that they are there for you to read and analyse… and that alone separates them from the rest of the DWFN.

With that said, I read with interest this paper, not just because of the agreements they have with two of the Pacific Islands I work with (Cooks and Kiribati), but also because of the work I have done inside the frameworks of agreements in African countries in the past (Guinea-Bissau, Mozambique, Senegal and Angola), and adding to that I know personally and have a lot of respect two of the authors.

Below is a summary, but as always, read the original!

Since the late 1970s, the European Union (EU) has negotiated fishing access agreements with developing coastal states, formalising the presence of its distant-water fishing (DWF) fleets in foreign waters. These agreements, which started with Senegal in 1979, have developed significantly over the past 45 years, reflecting shifts in geopolitical dynamics, economic interests, and sustainability concerns. This blog post offers a comprehensive overview of the findings from a recent study that examined the scope, scale, and impact of these agreements.

The Origins of EU Fishing Access Agreements

The foundation for modern fishing access agreements was established in 1982 with the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). This treaty introduced the concept of Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZs), granting coastal states sovereign rights over marine resources within 200 nautical miles of their shores. Article 62 of UNCLOS requires coastal states to promote the optimal use of living resources and to permit other states access to surplus resources through agreements.

For the EU, these agreements offered an opportunity to address overfishing in its domestic waters by reallocating surplus fishing capacity to resource-rich waters of developing countries. This expansion was also motivated by the need to satisfy the EU population's increasing demand for seafood. Over time, the EU established a wide network of fishing access agreements, mainly with African and Oceanian countries, many of which were former colonies.

Evolution of EU Fishing Access Agreements

The study highlights three distinct phases in the development of EU fishing access agreements:

1980s Expansion, during which the EU began with a single agreement with Senegal in 1979 and expanded to 12 agreements by the end of the decade. These agreements targeted a broad range of species, including coastal and demersal fish.

Peak Period (1990s–2000s) saw the highest number of agreements, averaging 14 at any given time, with geographical expansion into new EEZs in Africa and Oceania. The agreement with Angola was condemned in 2004, indicating the beginning of a decline. Recent

Decline (2010–2025) reflects a reduction to nine active agreements as of January 2025, driven by shifting geopolitical and economic interests and by increasing concerns about sustainability and fairness.

Key Trends in EU Fishing Access Agreements

The study highlights several significant trends in the composition, distribution, and economic scale of EU fishing access agreements:

Shift in Target Species: Early agreements targeted a diverse range of species, including coastal and demersal fish. Over time, the focus shifted primarily to large pelagic species, such as tuna, which now dominate the EU’s fishing efforts.

Reduction in Fleet Size: The number of EU vessels engaged in DWF operations has declined markedly, from a peak of 1,812 in 1999 to a median of 676 since 2020. This decline is primarily attributable to the reduction in bottom trawlers and dredgers, particularly from Spain.

Subsidy Allocation: Public subsidies have played a vital role in supporting EU fishing access agreements. Interestingly, small pelagic fisheries, which account for only 4% of vessels and 7.6% of tonnage, received 63.9% of the total €4.8 billion in subsidies allocated over 45 years. In contrast, large pelagic fisheries, which account for most of the fishing effort, received just 10.2% of the subsidies.

Geopolitical and Geoeconomic Dynamics: The study highlights how power imbalances shape access relationships. Coastal states often lack the industrial and financial capacity to develop competitive domestic fishing fleets, making them dependent on income from access agreements. However, these agreements can deepen inequalities, limit local access to seafood, and underestimate the value of resources extracted from their waters. (Yet in my opinion, this can be said about ALL fisheries agreements, at least the EU ones have funds earmarked for development and capacity building, something that others don’t.)

Case Studies: Morocco and Senegal

The study provides detailed case studies of Morocco and Senegal to illustrate the complexities of access relations:

Morocco: The EU’s agreement with Morocco has undergone significant changes over time. At its peak in the mid-1990s, the agreement offered considerable fishing opportunities for small pelagics, demersal species, and large pelagics. However, by 2023, the scope of the agreement had been greatly reduced, with limited opportunities for demersal species and large pelagics. The future of this agreement remains uncertain, as the Court of Justice of the EU recently ruled that including disputed waters in Western Sahara is illegal.

Senegal: The EU’s agreement with Senegal, the oldest in its network, has faced multiple challenges. It was terminated in 2006 under President Abdoulaye Wade, who prioritised local artisanal fishers and sought to protect overexploited fish stocks. Although the agreement was reinstated in 2014 under President Macky Sall, it faced strong opposition from local fishers and environmental groups. In late 2024, the EU and Senegal failed to renew their agreement, leaving its future uncertain.

Challenges and Implications

The study identifies several challenges associated with EU fishing access agreements:

Sustainability Concerns: Overfishing by industrial fleets, both legal and illegal, has depleted fish stocks in many coastal states. This has serious consequences for local fishers, forcing them into economic hardship and increasing irregular migration.

Transparency Issues: Although the EU’s agreements are regarded as the most transparent among DWF nations, there remains a lack of comprehensive data on the scope and characteristics of EU fleets operating in foreign waters.

Geopolitical Tensions: Agreements are influenced by complex geopolitical and geoeconomic factors, including colonial histories, trade treaties, and spheres of military influence. These elements often cause tensions between the EU and coastal states.

Equity and Fair Benefit-Sharing: The study emphasises the disproportionate distribution of subsidies to a small portion of the EU fleet, raising concerns about fairness within the EU and between the EU and coastal states.

The Future of EU Fishing Access Agreements

The future of EU fishing access agreements remains uncertain. The network of agreements has continued to evolve, and this trend is likely to persist. The EU faces a dilemma: it can either continue supporting its industrial fleets in foreign waters, which may cause local and regional resentment, or pursue more cooperative arrangements that emphasise fair benefit-sharing, local development, and sustainability.

Coastal states, on the other hand, will continue to examine different arrangements to optimise the use of their fishing grounds. This may involve partnerships with non-EU fleets or alternative approaches such as joint ventures. The study highlights the need for future research to compare the relative advantages of various access arrangements and to better understand the implications for sustainability governance.

Conclusion

EU fishing access agreements with coastal states of the Global South exemplify broader struggles over sovereignty, equity, and sustainability. While these agreements have secured the EU’s DWF fleets relatively stable access conditions, they have also revealed multiple tensions between economic interests, resource sustainability, and other factors.