Most of my current work is on the MCS. PSM and labour side – it wasn’t always like that… For over a decade, the central focus of my job was EU market access from both the sanitary and IUU perspectives. I was heavily involved in helping many countries access or maintain sanitary authorisation and remove yellow cards.

On the sanitary side, my area of specialisation was vessels and landing sites. In that domain, I carried out extensive work for the EU through its Better Training for Safer Food (BTSF) programme. Subsequently, I focused on drafting EU market access guides that explain the complex double authorisation system countries must navigate to export to the EU. The latest version I wrote for FFA is here.

While it is a long story, one of the tenets that the EU had was that when tuna was frozen in brine (as in purse seine), it could be ONLY used for canned tuna, and such could be maintained along the cold chain at -9°C while in brine, which had to be kept at -18°C if held in “dry” (as opposed to “wet” while in brine) stores.

This is because 30 years ago, if you had brine (seawater and salt in a highly concentrated solution often maintained at around 21% to 23.3% salt by weight), the density increased the cooler you made it… to a point that beyond -15°C it became challenging to circulate with the standard pumps and pressures we had at the time; furthermore, the fuel consumption increased significantly the cooler the brine became.

If you are interested in the process and physics of freezing, you can download and read this chapter of a book I co-wrote years ago about cold chains in fishing.

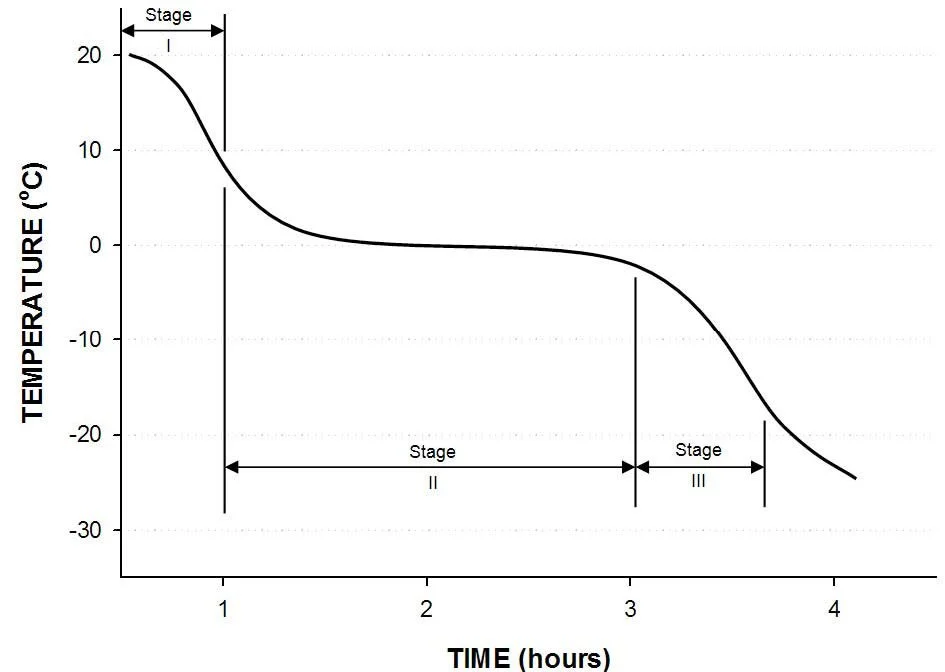

In summary, fish are mainly water, typically 60–90 per cent depending on the species, and freezing converts most of this water into ice. Freezing involves removing heat, and fish from which heat is extracted decrease in temperature, as illustrated below. During the initial cooling phase, the temperature rapidly drops just below 0°C, the water's freezing point. As more heat needs to be removed in the second phase to turn most of the water into ice, the temperature changes only minimally; this is known as the period of "thermal arrest". When approximately 55% of the water has frozen, the temperature begins to fall sharply again, and during this third phase, most of the remaining water freezes. This final stage requires removing only a small amount of heat.

Temperature-time graph for fish during freezing

Fish quality mainly depends on the speed of freezing, especially the time it takes to reach -5°c. At this point, ice formation begins through nucleation, where supercooled water molecules organise into a stable, ordered ice crystal structure. This initial "nucleus" then expands rapidly, releasing latent heat and causing the surrounding liquid to freeze; the faster this process happens, the smaller the ice crystals within the cells, resulting in less cellular damage and better quality when the fish is thawed.

Purse seine brine freezing is intended to quickly freeze large quantities of fish, which works well but compromises quality and salt penetration in the surface tissues beneath the skin. For many decades, this was not an issue because all PS fish was destined for canning, where tuna is peeled and overcooked twice (once before canning and then again in the can).

In the old days, no one sensible would take a skipjack or a yellowfin that had been three weeks in messy brine and cut it up for steaks... That is what you do with longline fish, which are killed individually and quickly frozen in blast freezers.

However, all of this changed in the last decade… in two ways;

FAD fishing: Before the nearly exclusive FAD fishery we have today, most tuna was caught in free schools… and these were very consistent in species composition… Usually, almost all skipjack and sometimes yellowfin. You might have encountered yellowtail Seriola lalandi (also known as yellowtail kingfish, hiramasa, or great amberjack), but not much beyond that. With the advent of FAD fishing, catches became very mixed, including yellowfin and bigeye (though mostly juveniles), which, of course, fetch a much higher price than skipjack in the direct-to-consumer market. This creates an incentive for fishermen to sell these as such, even if they were frozen in brine and intended only for canning. If not for canning, they could only be stored at temperatures below -18°C.

Certainly, this caused many issues for the CA of the flag states regarding control, as well as for consumers experiencing histamine problems. When tracing back through the chain, the catching vessel is a PS, so that fish should not have entered the direct human consumption value chain.

Better and newer vessels; a lot of newer vessels started setting some of dry lockers at the stern as blast freezers, so the fish is brailed on board, and the crew take the bigger yellowfin and freezes them there and creates a 2nd stream of freezing on board, which then is aimed at the ready-for-human-consumption value chain of frozen tuna. Yet on newer vessels, more efficient refrigeration systems allow freezing in brine at -19 to -20°C by tweaking and fine-tuning brine density between 19.8° and 22° in the Baumé scale. It is also essential to work with the lowest possible suction temperatures in the cooling system available

So, with all these changes, the EU has faced the need to update its regulations to reflect reality. One of my friends in DG SANTE approached me about this in 2021, so it has been in progress for some time.

Audits and official controls have shown that some tuna suppliers have falsely sold canned-grade tuna frozen in brine at -9°C as suitable for direct ‘fresh’ human consumption within the EU market. This practice endangers consumers by exposing them to scombroid food poisoning caused by potentially high histamine levels. The issue has been confirmed by an increasing number of notifications issued via the EU’s Rapid Alert System for Food and Feed (RASFF) concerning histamine levels exceeding permissible limits in vacuum-packed, thawed tuna loins treated with additives to imitate freshness, leading to confirmed cases of food poisoning.

Finally, on 29 October 2025, the European Commission (EC) officially adopted Delegated Regulation (EU) 2025/1449, amending Annexe III of Regulation (EC) 853/2004 to establish new standards for frozen tuna in brine. Under the new rules, only vessels proven capable of maintaining a continuous freezing process that reduces core tuna temperatures to –18°C may use brine freezing for tuna destined for direct human consumption.

The regulation requires that temperature reduction be continuous. For direct brine freezing, whole round tuna must reach –18°C within 96 hours of first entering the brine and must drop below 0°C within 24 hours. If first cooled in clean seawater, the water must be cooled to 3°C within 6 hours and to 0°C within 16 hours. Once in brine, the tuna must reach –18°C at its centre within 72 hours.

Interestingly, adding to the EM world, to ensure process integrity, freezer vessels must be equipped with real-time electronic brine-temperature monitoring systems that transmit data onshore, allowing food business operators and authorities to access them.

Furthermore, operators must develop a validation plan that demonstrates their vessel’s freezing capacity, including kinetic studies linking brine temperature with core tuna temperature, and certification confirming that temperature sensors meet international measurement standards.

Authorised third-country Competent Authorities (CA) are responsible for reviewing this plan during their vessel’s approval or listing process. The amended regulation is set to come into force from 27 January 2026.

This would introduce significant complexity to the systems of the four countries (PNG, Fiji, Solomon Islands, and Kiribati) in the WCPO (hopefully five soon, now that RMI is being evaluated).

The issue is that most of the PS are only flagged to the country, but their home ports are in TW, CN, and KR, where they used to be flagged. While EU rules are meant to be applied equally across all EU-authorised countries, most of these vessels appear to breach these regulatory requirements only when they fly a Pacific Island country’s flag. They complain that the regulations are too demanding and that KR or TW CA never asked for anything like an HACCP plan.

I have boarded hundreds of DWFN-flagged PS ships over the past 20 years. Most of them should not have been approved, as they do not meet even the basic requirements... and since they haven't been in the home port for over two years, they haven't been inspected at all... so the EU DG SANTE expects a lot from countries like RMI to prove they have CAs that are equivalent to those in Germany or France. Yet, the CAs of KR, TW, and CN seem to have no control over their vessels outside their waters.

While I endorse the changes that DG SANTE has implemented, and if I were in a position where my opinion mattered, I would advise that DG SANTE, either directly, through MoUs with national CAs, or with support from the EU delegations (where they already have DG MARE staff), station officers in the main Pacific ports. These officers should conduct independent boarding operations to ensure a level playing field for the Pacific Islands and the DWFN.

In my professional opinion (I used to train EU seafood inspectors), such DWFN vessels/fish should not be approved for EU exports, and their CAs should have their authorisations suspended.