The two times I wrote about work by John DeBeer (here and here), I mentioned that I grew up in a culture where you always listened to and respected your elders. This was later emphasised by my time in the Navy and then in fishing, as well as by the Pacific cultures that have hosted me in my new home since 1991.

You may not always need to agree with them, but you listen, because they have two things that only time can give context and perspective.

I completely devoured the latest book by John (and a bunch of other well-known tuna experts), A Personalised History of the U.S. West Coast Tuna Industry, as soon as the copy he kindly sent me arrived home.

He and some of the other authors are the elders in the tuna world I’m part of, and he has always been very kind with his time to my questions and views. So if you want to understand the tuna industry from the perspective of where it started and in 1rst person experience, I recommend you get a hard copy or the Kindle one

The tuna industry is shaped by people on deck and in the engine room, by salt, steam, diesel, deck machinery, net materials, refrigeration technology, and political negotiations, and carries the smell of used brine and geopolitics equally.

A Personalised History of the U.S. West Coast Tuna Industry is not merely a chronology of boats and brands. It is a study in access. Access to fish. Access to markets. Access to ports. Access to regulation. And, increasingly, access to survival in a world where fisheries biology, economics, and policy collide with ruthless indifference to each other.

The authors start where all fisheries must: with the raw material. No access, no fish. No fish, no cannery. No cannery, no brand. No brand, no industry. It is an elegantly simple equation — until the world intervenes.

Here are my lessons learned… but please read the original.

From Ice to Brine: Extending the Horizon

In the early 20th century, the tuna fishery off California was modest, almost intimate. Albacore were taken by small pole-and-line vessels operating within reach of shore. Ice was the limiting factor — both literally and economically. Fish could only be kept so long before decomposition turned profit into loss.

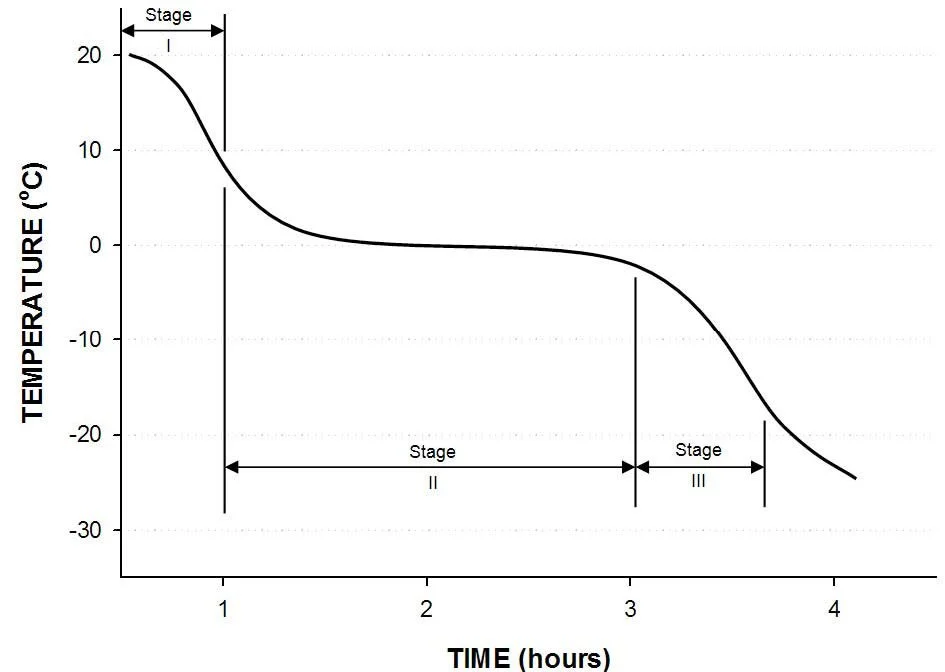

Then came brine freezing in the 1930s. Ammonia-cooled wells replaced ice. Trip length lengthened. Fishing grounds expanded southward. What appears to be a technical adjustment was, in fact, a structural transformation: technology dissolved geography.

This is the recurring theme of the book — every technological innovation changes not only efficiency but also power.

The fishery became less coastal and more industrial. And once the range extended, the next question was inevitable: how far can we go?

The Purse Seine Revolution

The Puretic power block and nylon nets in the 1950s transformed tuna fishing from artisanal harvest to industrial extraction. Cotton nets gave way to mechanised retrieval. Capacity exploded.

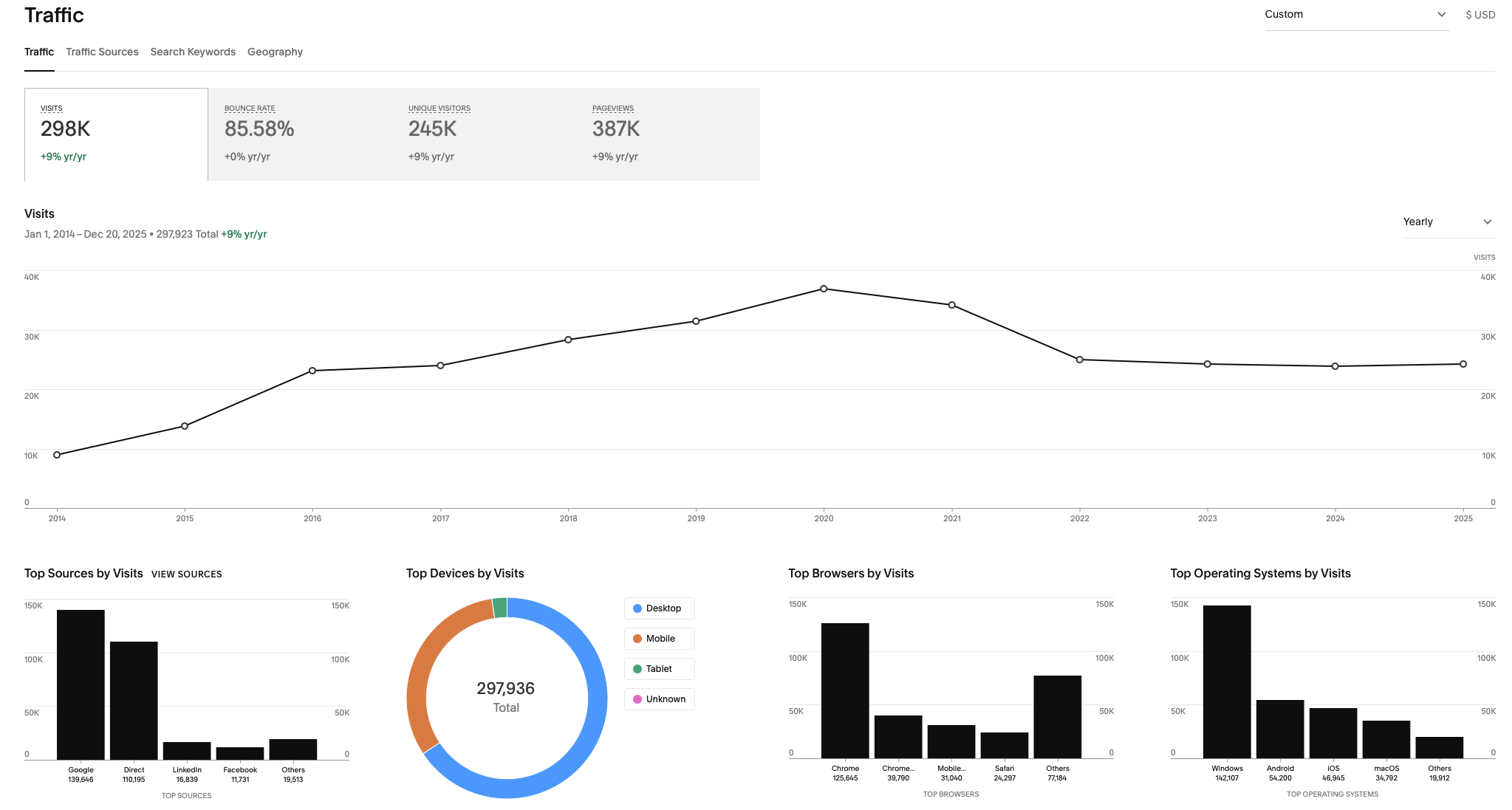

The IATTC data reproduced in the book show a surge in carrying capacity from the 1960s through the 1980s. Steel hulls replaced wooden ones. Shipyards in San Diego and Tacoma produced purse seiners like factories manufacture machinery.

And machinery was exactly that. Catch rates increased. Efficiency rose sharply. The fleet turned into a harvesting machine — until the shore-based infrastructure could no longer keep pace.

Cannery processing capacity is not infinitely elastic.

The Cannery: The Other Constraint

One of the most insightful parts of the book is not about fishing, but about processing. Canneries operate for 48–50 weeks each year. They are built for consistent throughput. Retorts, seamers, precookers, and thawing capacity — all fixed.

When purse seiners flooded the docks with frozen tuna in the 1980s, inventory management — not fish availability — became the bottleneck. Boats were ordered to tie up for 60 days after unloading.

That is a crucial insight. Overcapacity in fisheries is often discussed in biological terms, but here it is industrial logistics that regulates the fleet. Canned inventory value surpassed capital assets. Too much fish became a liability.

It was the market, not the ocean, that set the limit.

Law Shapes Geography: Jones and Nicholson

If technology broadens the range, then law redraws it.

The Jones Act (1920) limited coastwise shipping to vessels built and registered in the U.S. The Nicholson Act (1950) restricted foreign-built fishing vessels from docking directly at U.S. canneries — except in certain territories.

These laws subtly reshaped the geography of tuna processing.

Puerto Rico prospered under tax incentives (Section 936), but only U.S.-flag vessels were permitted to unload directly. American Samoa received a special exemption that allowed foreign vessels to land fish there and to ship canned products duty-free to the mainland.

Thus, the policy created an industrial shift. Canneries relocated overseas. By 2025, Puerto Rico’s tuna factories had all closed. Only one major cannery remained in American Samoa. Mainland operations transitioned to frozen loins imported from global precooking plants.

What started as a West Coast round-fish industry developed into a global loin-processing system.

Transhipment: The Invisible Artery

Few outside the industry appreciate the logistical ballet described in the chapter on Marine Chartering Company’s reefer fleet.

In the 1950s, tuna caught off Peru had to travel 4,000 miles to California. Grace Lines' cargo vessels were inefficient for frozen fish. MCC introduced small dedicated reefers. Ultimately, a global neutral freight network transported millions of tons of frozen tuna across oceans — from Peru to Puerto Rico, West Africa to Spain, Western Pacific to Pago Pago.

Transhipment is not glamorous, but it is crucial. It allowed fleets to stay on the grounds. It separated catching from processing. It facilitated the global reorganisation of tuna flows.

And when the neutral freight model was replaced by trader-controlled vessels, control of logistics shifted to control of sourcing and pricing.

Again: power shifts with infrastructure.

The 200-Mile Revolution

If the 1950s were a technological revolution, the 1970s/80s were a jurisdictional revolution.

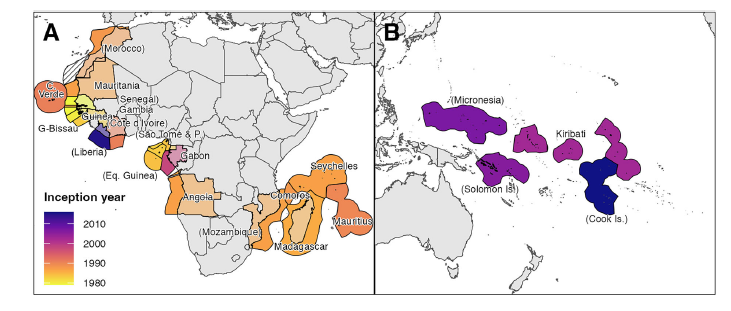

The spread of 200-mile Exclusive Economic Zones fragmented the high seas into national jurisdictions.

Highly migratory tuna do not respect borders. But vessels must.

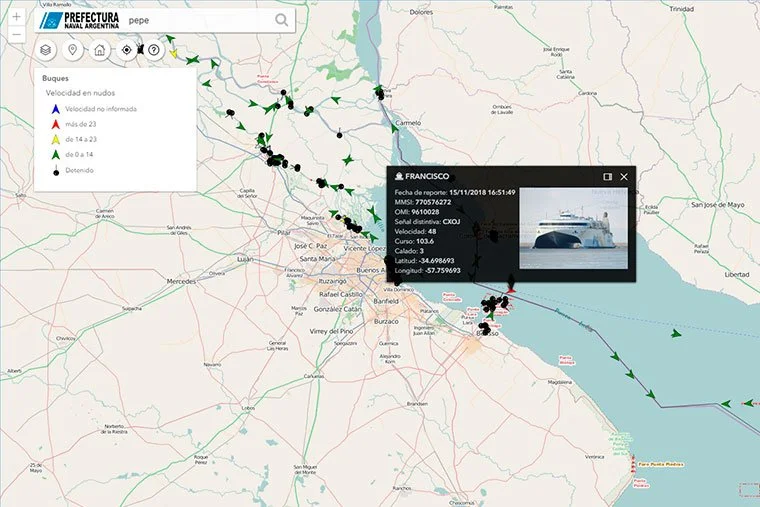

Suddenly, access required diplomacy. The American Tunaboat Association negotiated with foreign governments. Seizures occurred. Access agreements became essential. (Read here if keen to know more about this.)

And so RFMOs emerged — notably the IATTC in the Eastern Pacific.

But closures — such as the Yellowfin Regulatory Area — prompted fishermen to innovate spatially. The renowned “Outside the Line” grounds west of the Commission area became viable alternatives.

The fleet was adaptable. If fish were not available within regulated areas, they searched outside them.

This is another enduring lesson: regulation rarely ends fishing; it redistributes it.

Moving West

Veterans of WWII had observed skipjack schooling in the Western Pacific. In 1970, U.S. ships advanced into the Western Tropical Pacific near Palau.

The move was initially unsuccessful. Nets designed for dolphin-associated yellowfin in the Eastern Pacific were too shallow for deeper thermocline conditions. Japanese vessels, with deeper nets and advanced electronics, outperformed them.

The Pacific Fisheries Development Foundation (PFDF) was established to investigate hidden fisheries. Survey trips were conducted, and lessons were learned.

By the 1980s, Western Pacific fishing and American Samoa processing had become key components of the U.S. tuna industry.

Again: technology meets fisheries biology meets policy.

Food Safety: Invisible Discipline

Parallel to the evolution of fishing, there was also regulatory evolution on land.

From the California Cannery Inspection Act (1925) to the 12D botulism standard, from HACCP to histamine controls, the processing chapters of the book remind us that tuna is not merely a commodity — it is a food safety risk if mishandled.

Salt penetration, honeycomb formation, mercury levels, sodium reduction, and low-acid canned food regulations—each issue demanded a technical solution.

Fishing and processing are inherently linked. If fish heat during transhipment, histamine levels increase. If brine seeps unevenly into the muscle, the texture deteriorates. If concerns about mercury rise, consumer confidence declines.

The fishery persisted because the industry invested in resolving these issues.

Human Machinery

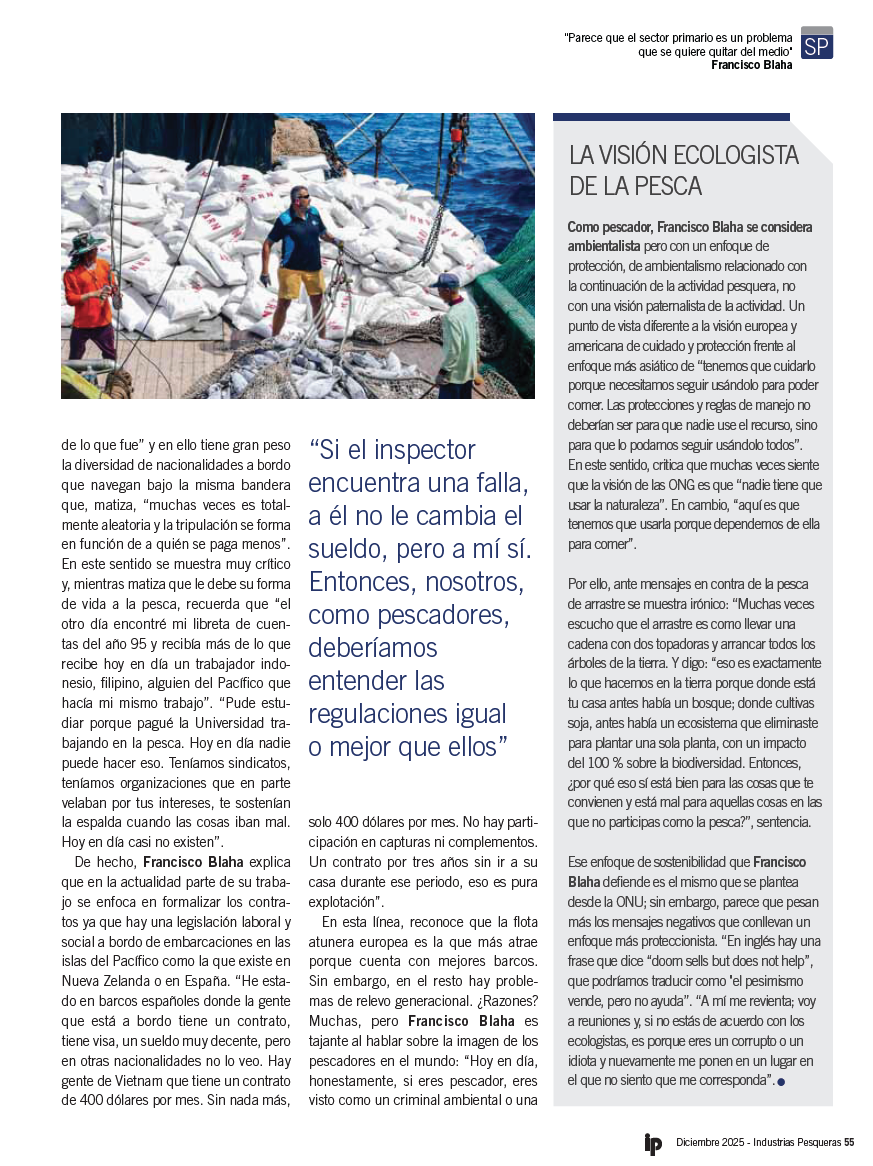

Perhaps the most compelling elements of the book are the vignettes — stories of boiler explosions in Samoa, of surly retort leadmen, of captains taking risks to fish in Peru, and of engineers tracing the foot of a 300-pound retort operator.

These stories are not merely decorative. They serve as reminders that fisheries are human systems. Decisions are made by people — sometimes impulsively. Machines explode. Nets tear. Governments change policy mid-season.

Behind every ton of tuna lies a web of human improvisation.

Rise and Decline of West Coast Canning

At its peak, dozens of canneries operated along the U.S. West Coast. By 2005, the last whole-fish cannery in San Pedro had closed. Production shifted to loins that were precooked overseas and imported for final packing.

The causes were well known: labour costs, foreign competition, transportation expenses, and trade regimes.

But beneath the economics lies a deeper structural shift: vertical disintegration. The old model — vessel to dock to cannery to brand — fractured. Catching, processing, and branding became geographically separated.

The U.S. tuna industry didn’t vanish. It reshaped itself.

Lessons in Systems

What does this century-long story teach me?

Access is political. Fishing grounds are negotiated spaces.

Technology outpaces governance. Every efficiency gain produces a regulatory response.

Processing capacity disciplines fleets. Biology is not the only constraint.

Logistics determines power. Who controls the transhipment controls value?

Industries globalise when cost structures demand it.

Human resilience underpins adaptation.

The tuna industry survived wars, EEZ revolutions, dolphin controversies, mercury scares, overcapacity crises, and globalisation. It did so not because it was static, but because it was adaptable.

And Now?

By 2025, the U.S. tuna processing footprint will be a shadow of its mid-century scale. But the system persists — reoriented around global loin supply chains, remaining territorial canneries, and distant-water fleets operating under RFMO regimes.

The book does not romanticise the past. It documents it — candidly, technically, occasionally humorously.

And it leaves us with a subtle but powerful realisation: fisheries are not just about fish. They are about alignment — between fisheries biology, engineering, regulation, logistics, labour, and markets.

When they align, the system hums. When they diverge, vessels tie up and factories close.

Tuna, the most migratory of fish, has borne witness to a century of industrial and political change. The story of the U.S. West Coast tuna industry is therefore not confined to local matters — it reflects a broader picture of global fisheries development.

Steel hulls. Nylon nets. Steam retorts. 200-mile lines. Reefer vessels. Tax codes. Scout planes. Observer programmes.

All in pursuit of a straightforward goal stated early in the book: to provide a wholesome, nutritious protein to people.

The journey from ocean to supermarket shelf is anything but simple. And that is precisely why this history matters.