As I wrote a few weeks ago, I don’t really have much of a work portfolio in Spanish, even if it was literally my mother’s language and the one in which I had my basic and university education.

I have worked more in Portuguese (which I learnt from living on the border with Brazil) than in Spanish itself. And as they say, no one is a prophet in their own culture. I have never worked again in Argentina since I left my last position at the National Institute of Fisheries and Development (INIDEP) in the early 90s

Yet in recent years, despite my strong views that the mess at the fishery in mile 201 stems from Argentina’s absolute (and shortsighted, in my opinion) refusal to even consider establishing an RFMO based on this, I have seen this as an implicit recognition of the Malvinas/Falklands Islands Government as a coastal state, thereby relinquishing sovereignty claims.

As someone who was involved in that war, I can see the basis of that reticence, yet I think it is totally misguided… You can manage the migratory resources without relinquishing sovereignty… There are a few examples in other RFMOs that prove that case.

In any case, I have been collaborating on the basis of two people with simmilar interest nd a comon past basis with Captain Sergio Almada, the Coordinator of Argentina’s Interdisciplinary Working Group for the Control of Maritime Areas and their Resources that depends on the country’s “Prefectura – PNA” (Coast Guard), from which he retired as a senior officer of patrol and surveillance vessels.

I have never met him personally, but as most former fishermen and skippers, you tend to develop a good sense for assessing people’s character, and Sergio seems to be a very good and solid seaman and professional… and I have no problems working with people like him.

We mostly discuss the technical analysis of vessel manoeuvring and the ground truthing of perceived vessel activities.

He also confronts a similar problem that many of us working on remote assessments via Maritime Domain Awareness (MDA) systems… the “desk experts”… which generally are very well-intended individuals that get hold of a Global Fishing Watch (or equivalent) account and start analysing fishing vessels’ tracks (generally without any fishing experience themselves) and propose their findings/theories in social media and something in the non-specialised press that is always up for “a one-line punch” to the work of specialists and institutions, casting doubt on their capacity and integrity…

And as “doom sells but does not help”, then the real specialists have to spend a second time debunking those opinions, instead of doing the work they are supposed to do.

Yet Sergio wrote a great article in Spanish, explaining some of the issues with “Desk Experts” and their work, and he was really kind to quote me and refer to my work a few times, for which I’m very grateful…. And I hope one day get to meet him personally

The original is here, in Argentina’s Revista Puerto and a semiautomatic translation follows below

When AIS deceives: the limits of remote monitoring against illegal fishing

Technology based on Automatic Identification System (AIS) data is a vital tool for monitoring and managing fishing activity at sea. When used correctly, it enhances surveillance, but not everything displayed or interpreted by these platforms or "desk experts" is accurate. Recognising its limitations and inaccuracies is crucial.

Starting with a false premise or inaccurate causes when addressing a problem reduces the chances of finding an effective solution. This principle is especially relevant to criminal activities at sea and is vital for researchers working at a desk behind a computer, analysing information from monitoring platforms.

Understanding how to interpret what these platforms show us, analysing and evaluating the quality and relevance of the information, and seeking to compare it with real-world evidence requires skill and the ability to validate and contextualise. This is often lacking, undervalued, or considered of little importance, especially when what is presented responds more to interests than to the pursuit of truth with the necessary scientific rigour in an investigation.

To paraphrase Francisco Blaha, a specialist in fisheries issues and an expert in validating hypotheses and providing operational filters for these remote desktop analyses, ‘focusing the solution to problems surrounding fishing activity at sea on a single tool, such as AIS, carries the risk of raising expectations about what this technology can offer excessively.’

Blaha states that if the hypotheses and indicators used by these platforms are adjusted and the methodology employed is better verified in the field, the results will be more reliable and the tool will be more effective to use, providing more realistic figures on the problems.

It is worth exploring Francisco Blaha's blog, which has been around for over a decade, where you can find his contributions to the conservation and sustainable management of fisheries, monitoring and control, decent work on board fishing vessels, and a practical, operational view of the activity. This makes his perspective unique, and for me in particular, more appealing and engaging.

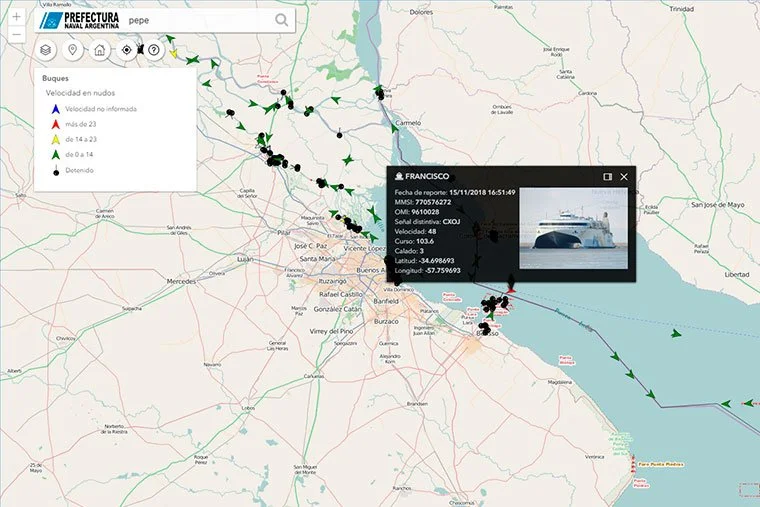

Fishing activity monitoring platforms not only display current and historical information about vessel identification and dynamics, but also report on their presumed activities (events), such as fishing, transhipments, encounters, navigation, anchoring, entry or exit from ports, AIS shutdown, and fishing effort, among others.

To achieve this, they employ a methodology, indicators, training data, and algorithms that enable them to define these activities, often with the assistance of artificial intelligence. In other words, their role in control and investigation is very significant, but it is not decisive for fully understanding what truly occurs around the activities, nor for addressing forms of maritime crime such as illegal fishing without room for error.

It is not conclusive because the information they present must not only be verified in the field but also contextualised at the local level, which requires genuine knowledge of the activity and consultation with its main actors. It is in this context that the figure of what some call ‘desk experts’ emerges and, together with them, the platform-expert binomial, which can be very effective but also potentially disastrous.

The outcome of the platform-expert collaboration will largely depend on the latter's ability to interpret and contextualise the information gathered from the platform, their knowledge of the sources and algorithms employed by the platform, their familiarity and experience with the activity under investigation, and the opportunity to engage with key actors who can validate the interpretation based on primary sources.

Common errors identified in these ‘desktop’ analyses

Few researchers verify their assumptions with the hydrometeorological data relevant to the event they are examining. Blaha highlights that anyone who has spent time on a ship knows that ‘weather is king at sea’ and that a ship's capabilities depend on sea conditions.

Not every time a ship maintains almost the same position for a couple of days is it engaging in illegal activity, as it is quite possible that when the AIS data is superimposed on the hydrometeorological data, it will be verified that it is actually weathering 50-knot winds and huge waves, where rather than illegal activity, it is simply trying to survive or ensure the safety of the ship and its crew.

Associating the entry into port of a fishing vessel or a refrigerated fishing support vessel directly with the arrival to unload catches, without considering that it may also be for other services and without consulting the port authorities to confirm or discard this assumption. For example, fleets such as the Chinese fleet operating in Mile 201 tranship their products on the high seas and rarely unload in port.

Considering the encounter of a fishing vessel with another fishing vessel or with a cargo vessel as a transhipment of catches, when there are many other operational reasons for encounters at sea, such as the provision of supplies, bait, fuel, spare parts, fishing gear, crew changes, and anything else we can think of. Analysing the duration of the encounter can be very helpful in identifying the reason.

It is a serious mistake to take for granted the boundaries that monitoring platforms present for the maritime spaces of coastal states without verifying that they correspond to the official ones.

Comparative experience across several Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZs) in South America indicates that the boundaries used by some of these platforms differ from the official ones, which often makes activities outside jurisdictional waters appear to be illegal fishing.

This issue has persisted for years regarding the Marine Regions boundaries used by Global Fishing Watch (GFW) for Argentina's EEZ, extending into the “Agujero Azul” / Blue Hole area to 4.4 nautical miles on the high seas. A similar discrepancy remains in the boundary between Uruguay's EEZ and Brazil's, with no corrections made so far.

Unequivocally linking illegal fishing to a vessel entering an area where it is not authorised to operate, without considering whether its movement patterns and dynamics are compatible with fishing activities for that type of vessel, thus failing to acknowledge the international right of free navigation that supports them.

Another issue identified in studies that track port arrivals using AIS is that poorly trained algorithms may mistake movements between anchorage areas, from these to port and vice versa, as new arrivals, significantly overestimating their numbers. This issue has been observed in studies on the arrival of fish cargo ships at the port of Montevideo.

It also leads to errors to analyse apparent fishing manoeuvres based on AIS positions without considering the type of vessel. This is because, depending on the fishing gear used by a vessel, the speed, fishing pattern, depth, and characteristics of the area of operation, and in some cases, even the time of day when the activity occurs, will vary, making it possible to associate it with an activity compatible with fishing for that type of vessel.

Associating the switching off of AIS directly with illegal activity without recognising that not all fishing vessels are required to carry this device or keep it switched on by their flag states, to whom international regulations delegate this responsibility, or that there are commercial competition reasons for doing so.

Added to this is the failure to consider that many coastal States, such as Argentina through its Coast Guard System, and various platforms for controlling fishing activity have the capacity to detect them using satellite imagery, regardless of their AIS transmission.

Finally, some machine learning algorithms on these platforms mistakenly classify activities as fishing that, to an expert, do not correspond to that type of manoeuvre for a given fishing gear. Such errors help to exaggerate fishing effort.

In conclusion, analysing the information from fishing activity monitoring platforms should not be done without taking the context into account.

Some trends identified by analysts, such as changes in service ports for distant-water fishing fleets due to stricter or, conversely, more relaxed controls, may simply reflect annual variations in fishery resources or commercial and logistical reasons when considered in context. For example, the collapse of the Tsakos Dock in Montevideo in December 2022 forced fishing vessels operating in Mile 201 to initially seek alternative ports in southern Brazil for repairs.

With proper use, interpretation, and contextualisation of the information, combining data from these platforms with the work of experts and researchers to monitor and control fishing activities is highly beneficial. However, if this combination fails, it can distort the reality of what is actually happening, potentially hindering efforts to find solutions, especially when such information is utilised by decision-makers.

This article is not intended to criticise monitoring platforms or the work of experts or researchers; on the contrary, the contribution of information and effort is highly valued. It simply aims to highlight the risks of using this technology out of context and without the necessary expertise.