I have reported in the past on excellent paper co-authored by my colleague Alex Tidd, obviously, he is on a roll. Last week, a new paper by him as the lead author was published and again is very good.

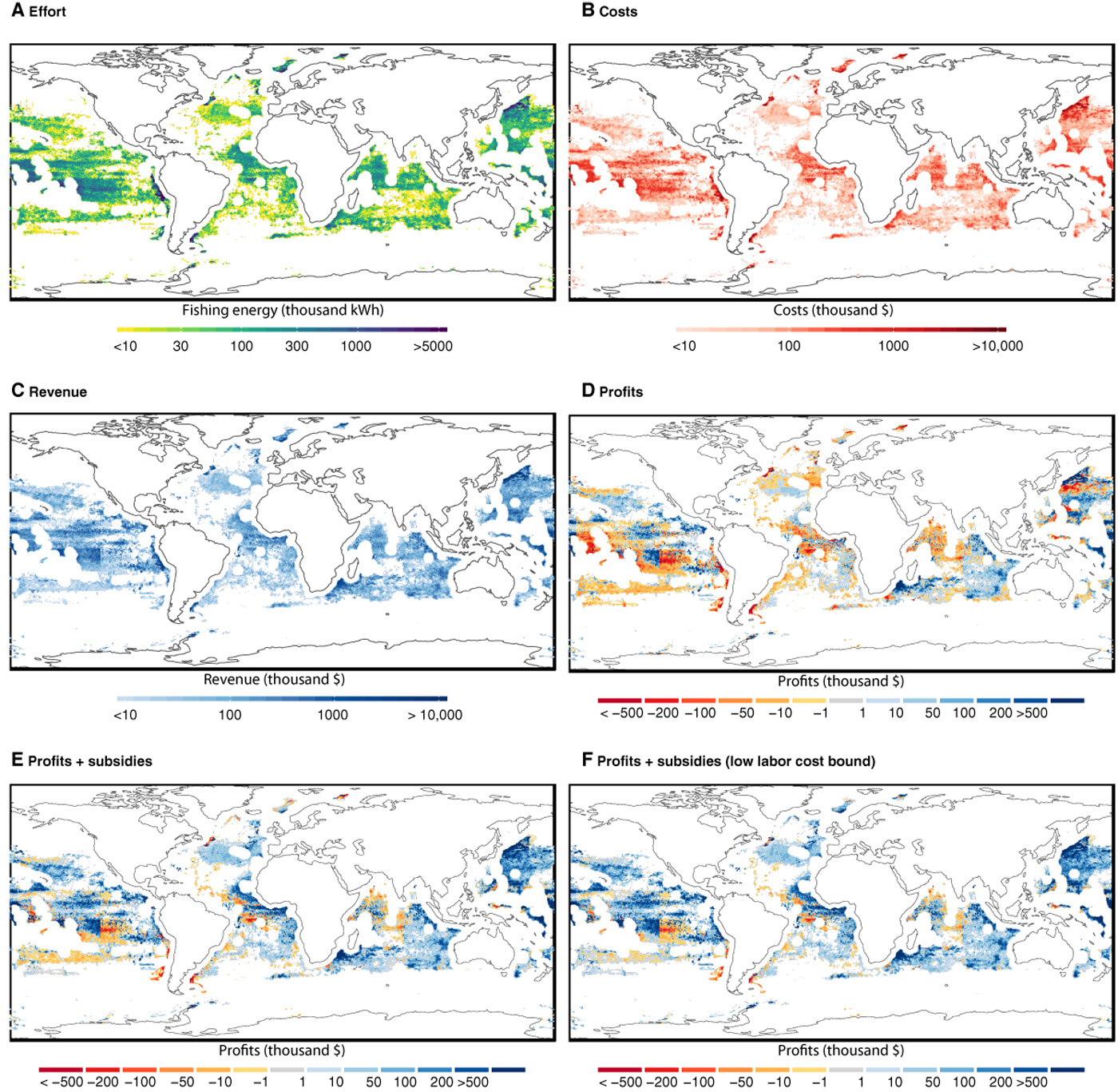

Model skill and cross-validation from the ridge regression analysis. (a) Pearson’s Correlation between feature variables, the plot uses clustering and the closer the variables are to each other the higher the relationship. While the opposite is true for widely spaced variables. The colour and thickness of the line represents the direction of the relationship and the strength.

I admire how people like him face an absurd amount of raw data, starts working ideas out, sits in front of a couple of screens and do R wizardry to do papers like this… relating fisheries to human development index (HDI) may sound bold, but makes total sense to me.

Tehre is the a subtantial lack of use of socio-economic data used by Tuna RFMO. Of course operational data may be hard to get access to but there is a lot of data out there that could be used to move beyond 1st base, as it is proven by this paper

For example some of the tuna RFMOs are starting to conduct Management Strategy Evaluations MSE’s on mixed fisheries, this requires identifying winners and losers.

Ironically in the tuna RFMOs when they do biological stock assessments they mainly use fisheries dependent data, but then the say we can not get the data to conduct social and economic analyses. If we can use fleet data to describe the biology then surely we can use it to model the fishery as well.

Is obviously not light reading and some of the graphs are in a “format” I have never seen before (as the one above) and that is a good thing! But what I like the most is not just the questions that answers but the fact that set up a framework for many more unmade yet questions that clever people like him will answer.

As usual, read the original! I will here only quote the abstract conclusion and a section I found very interesting in fuel consumption.

Abstract

Overfishing impacts the three pillars of sustainability: social, ecological and economic. Tuna represent a significant part of the global seafood market with an annual value exceeding USD$42B and are vulnerable to overfishing. Our understanding of how social and economic drivers contribute to overexploitation is not well developed. We address this problem by integrating social, ecological and economic indicators to help predict changes in exploitation status, namely fishing mortality relative to the level that would support the maximum sustainable yield (F/FMSY). To do this we examined F/FMSY for 23 stocks exploited by more than 80 states across the world’s oceans. Low-HDI countries were most at risk of overexploitation of the tuna stocks we examined and increases in economic and social development were not always associated with improved stock status. In the short-term frozen price was a dominant predictor of F/FMSY providing a positive link between the market dynamics and the quantity of fish landed. Given the dependence on seafood in low-income regions, improved measures to safeguard against fisheries overexploitation in the face of global change and uncertainty are needed.

Over the last two decades there have been significant changes in fuel costs, fish prices, global warming, technological change (i.e. introduction of gears such as Fish Aggregation Devices, FADs), and changes in adult tuna stock biomass. All of these factors have a cumulative effect on the operating costs of fleets and thus their spatial behaviour. For tuna stocks, past exploitation levels and management measures have shown to be as important as the links between life history, market price and vulnerability to overexploitation. Although a composite index of fisheries management at the country-level has shown to be positively related to factors such as countries’ gross domestic product an integrated understanding of how these drivers connect to environmental with economic and biological variables for tuna stocks is currently missing.

Here we examine whether tends in tuna stock status, as measured by F/FMSY, are related to the economic and social development of countries (Human Development Index, HDI) to identify whether some countries are more risk of overexploitation. We then develop statistical models to explore how stock status could be affected by different types of short-term shocks based on the relationships between F/FMSY with economic fluctuations (e.g. fish prices and fuel price), social (fleet diversity/fishing activity – knowledge transfer) and climatic variability (e.g. North Atlantic Oscillation Index (NAO) and Southern Oscillation index (SOI)). Time series of economic, climatic and spatial indices were available for more than 23 years. As these indicators are potentially correlated, we constructed ridge regression models (see Methods and Materials) and used these to assess the sensitivity of F/FMSY for tuna stock to each driver of change.

I found their analysis as regards fuel consumption quite interesting:

Fuel price was also dominant predictor of F/FMSY across all stocks, with a 25% change in fuel price resulting in a 1.6% max change in F/FMSY, providing a positive link between the money spent and invested by a fleet, and the quantity of fish landed. Although this is a small increase and probably the offset effect of favourable frozen tuna prices and increases in technical efficiency, this can, however, have positive or negative effects on the stocks, i.e. such an increase in fuel price could have a large effect on the stock by reducing fishing mortality but quite the opposite effect from a drop in fuel price if not properly regulated. Either way, this substantial effect could be detrimental to the industry and the resource, or both. Many small-scale operators (e.g. the pole and line fleets) perhaps would have less opportunities for social change i.e. potentially a decline in fleet size or diversity (in terms of fishing areas and/or species) that could in turn have lasting effects in terms of food security for some coastal communities. Longlining for tuna is on average up-to four times more fuel intensive per ton of catch than purse seining but the difference is very much smaller than that in specific fuel consumption per ton of catch, because of increases in fish prices for the better quality product. With much of the industry worldwide supported by government’s subsidies for fuel (in the western central Pacific alone worth in excess of US$335 million), a price drop in fuel costs could lead to harmful and wasteful fishing practices. Therefore controlling fishing effort levels in the future via competitive fuel pricing and/or controlled market incentives such as encouraging the use of fuel-efficient technologies will be of great importance to global tuna fleets. In contrast, the species price effect resulted in a negative coefficient (both fresh (4%) and frozen (13%)), which is counter-intuitive to the expected behavior of fishers. Production sensitivities are usually positive; a higher price (Ceterus paribus) will lead to increased production. Although an elastic price effect of demand may occur whereby a moderate increase in catch will result in a substantial decrease in price. However, in the case of purse seine fishers, it may be that the fishers target a higher abundance of fish even if the price is lower, therefore with overall higher total benefit. Fresh and frozen prices were included in this model to capture the dynamics of the sashimi and cannery markets, but maybe at the time of fisher decision-making the difference in price between fresh and frozen may not be relevant and therefore a composite measure of price would have been more appropriate proxy. Further, the quantity of frozen tuna can potentially be controlled in deep freeze and the quantity adjusted to market demand. It is also important to note that the fishing mortality on most tunas has increased, which could also explain the negative effect.

Conclusion

Tuna represent an iconic aquatic species that are important to many nations worldwide, not only for employment or economic returns from fishing, but are socially and culturally integral to local coastal communities as well as for the ecosystem. Our analysis has demonstrated how correlated social, economic and environmental variables can be combined in a simple model that can help to assess vulnerability to overexploitation and thus allow time for preventable management action.

Fisheries management has progressed over the course of the 20th century, but given the large proportion of stocks that are depleted or over-exploited, the threat to many coastal communities, and the increasing number of marine species that have been lost or listed as endangered, there is still a clear need for improved management. Our approach is necessarily simplified in that we analysed trends relative to fixed references points from stock assessment outputs. In reality changes in stock structure and environment will change FMSY (and also MSY and BMSY). Future work could aim to address these influences in more depth by integrating environmental variables into dynamic population models.