I get ask a lot about the shark fishery and its issues by my non fishery friends, who they normally assume that if I work in fisheries then I should know… and while I’m a generalist by nature I do have my specialities and Sharks isn’t one of them. Is a bit like saying to a Civil engineer that make bridges about dams, he may know the basics, but hardly can give much advice.

On the other side… I always say that if I you don't know something, the next best thing is to know the person that knows about it. And when it comes to shark capture and trade, Shelley Clarke is the person (she actually is one of those rare individuals that knows a lot about a lot… and sharks is one of her many topics). At the present she is the Technical Coordinator-Sharks and Bycatch, Areas Beyond National Jurisdiction Tuna Project, Western and Central Pacific Fisheries Commission

Last years she published an article in the SPC Fisheries Newsletter, where she analyses 4 commonly held suppositions, that the interested public has on shark fisheries, which I’ll quote in this post.

Am I eating shark?

Demand for this luxury product is one of the reasons why there are extensive and centuries-old trade networks linking China with far-off countries. Ironically, despite its venerated status, the Chinese refer to shark fin simply as yú chí (鱼翅, fish fin) rather than using the Chinese words for shark (shāyú, 鲨鱼). This may be the reason why some surveys report that consumers do not always know that the product is derived from sharks.

The Chinese are not alone in failing to recognize sharks on their plates: sharks have long been used, often under other names, as the “fish” in fish and chips in Europe, Australia, New Zealand and elsewhere. Therefore, while sharks have become conspicuous as entertainment since the 1970s, they have been important as commodities for centuries.

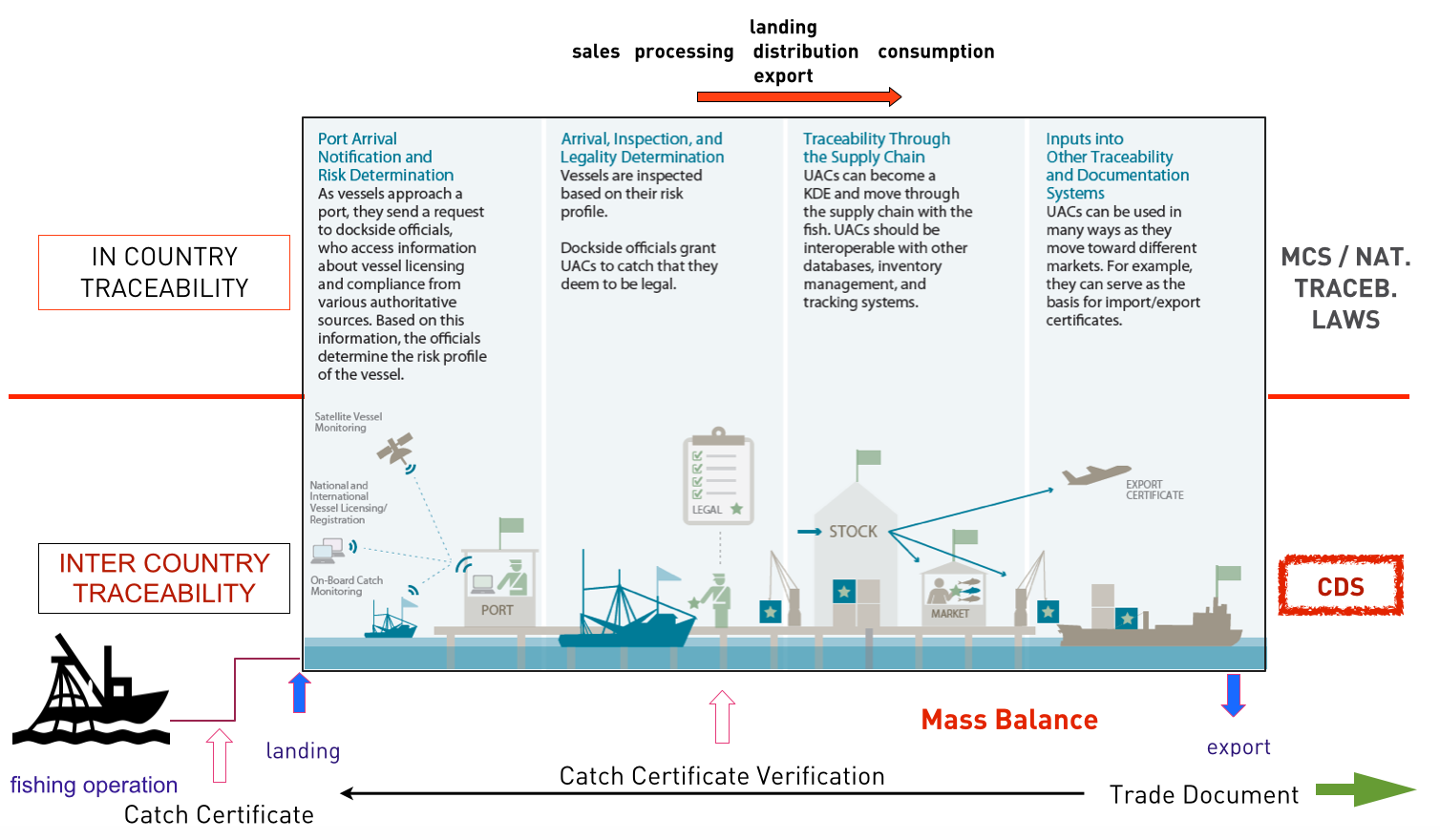

In September 2014, the implementation of multiple new listings for sharks and rays by the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) of Wild Fauna and Flora (see below), underscored the need to re-kindle interest in using trade information to complement fisheries monitoring.

These CITES listings are a spur to integrate international trade information with fishery management mechanisms in order to better regulate shark harvests and to anticipate future pressures and threats. To highlight both the importance and complexity of this integration, this article will explore four common suppositions about the relationship between shark fishing and trade and point to areas where further work is necessary.

Supposition #1: Banning finning will reduce shark mortality

Many conservation campaigns have attacked the shark fin trade on grounds of animal cruelty (live finning), unnecessary waste (discarding of shark carcasses at sea), being unsustainable (overexploitation), or a combination of these. As a result shark finning — the practice of removing a shark’s fins and discarding its carcass at sea — is banned in many fisheries. Setting aside for the moment the issue of whether all the different formulations of these bans are enforceable (e.g. the 5% fins-to – carcass ratio), it is important to note that even under perfect enforcement, finning bans may fail to reduce shark mortality. This is because finning bans do not regulate the number of sharks killed, only the way in which they are killed.

For fisheries that primarily want sharks for their fins, unless there are catch controls in place in addition to the finning controls, for example as in New Zealand’s Quota Management System, an unlimited number of sharks with valuable fins can be retained and landed, with the fins sold and the carcasses dumped. Alternatively, there may be high demand for shark meat and, therefore, no incentive to fin sharks and discard carcasses at sea.

A recent analysis in the Pacific found that even before the finning ban, overfished oceanic whitetip and silky sharks were more likely to be retained than finned. With or without a demand for shark meat, as long as the fishery is able to accommodate the storage and transport of shark carcasses to port, a prohibition on finning sharks may make no difference to shark mortality rates. Bans on finning in the absence of catch controls also do not prevent fishermen from intentionally killing and discarding sharks; for example, to reduce bait loss on future sets.

There is growing recognition that shark management and conservation must look beyond simply regulating finning, but effective measures to control shark mortality within sustainable limits remain to be adopted and verified in most national and international waters. One benefit of an increasing demand for shark meat should be that it is easier to identify shark carcasses (as sharks, if not always to species) at transshipment, port and border inspection posts as compared to shark fins which can be dried and packed away with other cargo.

Supposition #2: Consumers are being influenced by shark conservation campaigns

Some shark conservation campaigns have focused their efforts on Chinese consumers in the hope that increased awareness of threats to sharks would reduce their consumption of shark fin. A report in the New York Times in mid-2013 quoting both campaigners and traders, suggested that the trade had declined as much as 70% from 2011 to 2012. While there is no question that the shark fin trade in Hong Kong and China has contracted, both the scale of the contraction and its causes are debatable.

A forthcoming study of Hong Kong shark fin trade statistics — the most accurate proxy for global trends— documents that imports have been dropping since 2003 and that the media reported declines of 70% from 2011 to 2012 reduce to ~25% when calculated using the proper adjustments for water content and commodity codes changes. China’s trade statistics for shark fin are less reliable than Hong Kong’s due to commodity coding issues, but there are also media reports of a dip in demand in the northern capital, often attributed to new rules for government hospitality expenses announced in late 2012. Additional support for the effect of these rules, which restrict purchases of “shark fin, bird’s nest and other luxury dishes”, comes from reports of declining sales of other luxury seafoods such as abalone, sea cucumber, lobster and crab.

But are shark conservation campaigns having any effect on Chinese consumers? It seems impossible to answer this question definitively, but independent interviews of 20 Beijing-based restaurateurs conducted just before the new government hospitality rules were announced offer some insight. All respondents agreed that consumption was falling, but there were divergent views on whether the conservation campaigns were the reason.

Some stated that diners were shunning shark fin dishes because they are unhealthy, passé, or, most importantly, likely to be made from artificial materials given the threatened status of sharks and the expected shortage of real fins (. Without fully understanding the scale or cause, it still seems safe to conclude that the demand for shark fin in China is waning and that sounds like good news for sharks.

Less encouraging is the finding by the new Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) analysis that Thailand has surpassed Hong Kong as the world’s largest exporter, and its main trading partners — Japan and Malaysia — may be among the world’s top four importers, particularly of small, low value fins. Not only do these markets show no sign of slowing down, they are all among the world’s top shark fishing nations and, thus, the full scope of their shark fin markets may be even larger than trade-based estimates suggest. When we add to this the facts that most consumer-orientated conservation campaigns target shark fins rather than meat, and that shark meat consumption is both growing and often unrecognized as “shark”, it is clear that the campaigns have more work to do.

Supposition #3: The trade will collapse when shark stocks become overfished

A third thorny issue at the intersection of shark fishing and trade is the ability of shark populations to support the global fin and meat trades. While many argue that shark populations have already begun to collapse, how have the high trade volumes for fins and meat been maintained for this long?

FAO maintains the only ongoing worldwide compilation of shark, skate, ray and chimaera (chondrichthyan) catches, and if we tally their catches reported as “shark” and “unidentified sharks and rays” they are 20% lower in 2010 than they were in 2000. The amount of catch reported as “skates and rays” is 16% lower. The amount of catch reported specifically as “sharks” has increased but this could be due to greater species-specific reporting rather than a real increase in catch. A fallback to levels of ~11–23% less than the peak is also visible in the Hong Kong shark fin import data for 2004–2011. Despite the potential for the relationship between shark catch and trade to resemble the relationship between chicken and egg, it ahs been concluded that the decline in reported chondrichthyan catches is due to overfishing, not a result of decreases in fishing effort or market demand.

Given the reproductive rates of most shark species, it may be surprising that these observed declines in catch and trade statistics are not larger. One possible contributing factor is species substitution. As shown in a forthcoming analysis, the relatively productive and distinctive blue shark is becoming a larger component of reported shark catches compared to the less productive, but equally distinctive and more valuable, mako shark. Therefore, it is likely that the shark fin trade is even more dependent on blue shark than it was in 2000 when that species supported at least 17% of the market.

There are already some visible signs of overexploitation in catch and trade statistics, and these may be damped down by substitution of more productive species for those whose populations have already collapsed, for example the oceanic whitetip shark. While there are complications in the data that hamper definitive conclusions, better catch reporting must be encouraged and more focused shark catch and trade analysis is certainly warranted.

Supposition #4: Prohibiting shark catches will curtail trade and reduce pressure on shark populations

It is easy to assume that forbidding fishermen to catch sharks will lead to a suppression of the shark trade and a conservation benefit for shark populations. But here, too, the devil is in the detail: both the ability and desire of fishermen to avoid catching and killing sharks need to be strong for this supposition to hold.

In tuna and billfish fisheries, sharks are caught alongside these target species in large numbers. Methods to reduce unwanted shark catches are a topic of active research but solutions appear to vary by fishery and may have economic or operational consequences. Under two forms of catch prohibition — no-retention measures for certain species and area-specific prohibitions for all species (sometimes referred to as “sanctuaries”) — sharks, if caught, must be released with minimal harm.

However, studies in the Indian and Pacific Oceans have shown that 81–84% of sharks do not survive their encounter with purse-seine gear. In longline fisheries it is estimated that 12–59% of commonly caught shark species will die before reaching the vessel 10–30% of those that survive haulback will die through handling, and 5–19% of those that survive handling will die after release.

Without having read the studies where this figure come from, but based on my experience as a fisherman and observer on these fleets, I’ll say they are about right… besides it is really difficult to deal with a shark once it is on deck. When I was working in the trawlers in Argentina an Angel shark (squatina) bit my foot, thankfully I had a steel cup boot, but that beast bent it in a way that trapped my foot and did not let go. We had to kill it and behead it, as to release the jaws from my boot and then I had to put my foot in a vice to saw the boot out of my foot… is stayed away from sharks since then…

In any case, with such high potential mortality rates for released sharks, it is not clear whether no-retention and “sanctuary” measures can reduce overfishing to sustainable levels. Whenever discarding sharks is seen by fishermen to come at a cost — for example loss of saleable products or increasing the likelihood that the next set will catch the same unwanted shark — enforcement must be strong.

Small Island Developing States often struggle to find the resources to conduct intensive patrols at sea. Even if catch prohibitions in “sanctuaries” are strongly enforced, vessels that want to continue to catch and retain sharks, or to kill unwanted ones, may move to other jurisdictions with fewer rules and less monitoring (such as the high seas) and continue to fish the same stocks.

Trade data can help to highlight areas where existing fisheries controls may need to be strengthened. For example, the Marshall Islands declared itself a shark “sanctuary” in 2011 by prohibiting both catch and trade. Nevertheless, Hong Kong government records show imports of 7.2 t of dried unprocessed Marshallese shark fins in 2012 and 2.5 t in 2013. Similarly, United States trade records show 16 t of frozen shark exported to Palau in 2012 and 15 t in 2013. While Palau may not have banned the trade in sharks, these exports suggest that the demand exists, either nationally or for onward trade, and this demand could undermine Palau’s designation as a shark “sanctuary” in 2009. These examples provide further impetus for integrating fishery and trade monitoring programmes.

This article has highlighted a number of ways that management of both shark catch and trade data can be integrated for conservation benefit Relating the following issues with the respective recommendations (in Italics.)

Monitoring trade data can help interpret stock status and identify future threats, but it is dangerous to focus on single products and markets (e.g. shark fins in China) because trade patterns may shift while catches remain high (e.g. increase in demand for shark meat). Fisheries management and trade measures need to focus on effective control of shark mortality, whether or not it is due to finning.

Consumers are influenced by a number of factors, only some of which relate to conservation concerns. Even consumers with preferences may not always be able to identify unlabelled shark products. Conservation campaigns focused on shark fins need to recognize the growth in the shark meat trade.

Despite overfishing, trade levels can appear stable or to be increasing due to improvements over time in species-specific catch reporting and substitution of more abundant species when less productive populations crash. Better catch and trade data are key to identifying early warnings of shark overexploitation.

Prohibiting shark catches should be complemented by improvements in bycatch reduction, adequate enforcement and development of trade surveillance programmes. Fishery and trade data should be used in conjunction to monitor compliance with regulations and overall stock status.