For a good brief of the highs and lows, my colleague Wez Norris (deputy director of FFA and sempiternal lender of his diving gear to me) made a great summary at the end of the session and responded some question that I transcribe below (original here)

FFA members came here with four highest priorities, and four high priorities and really happy to note there has been good progress on three of the highest priorities and one of the high priorities.

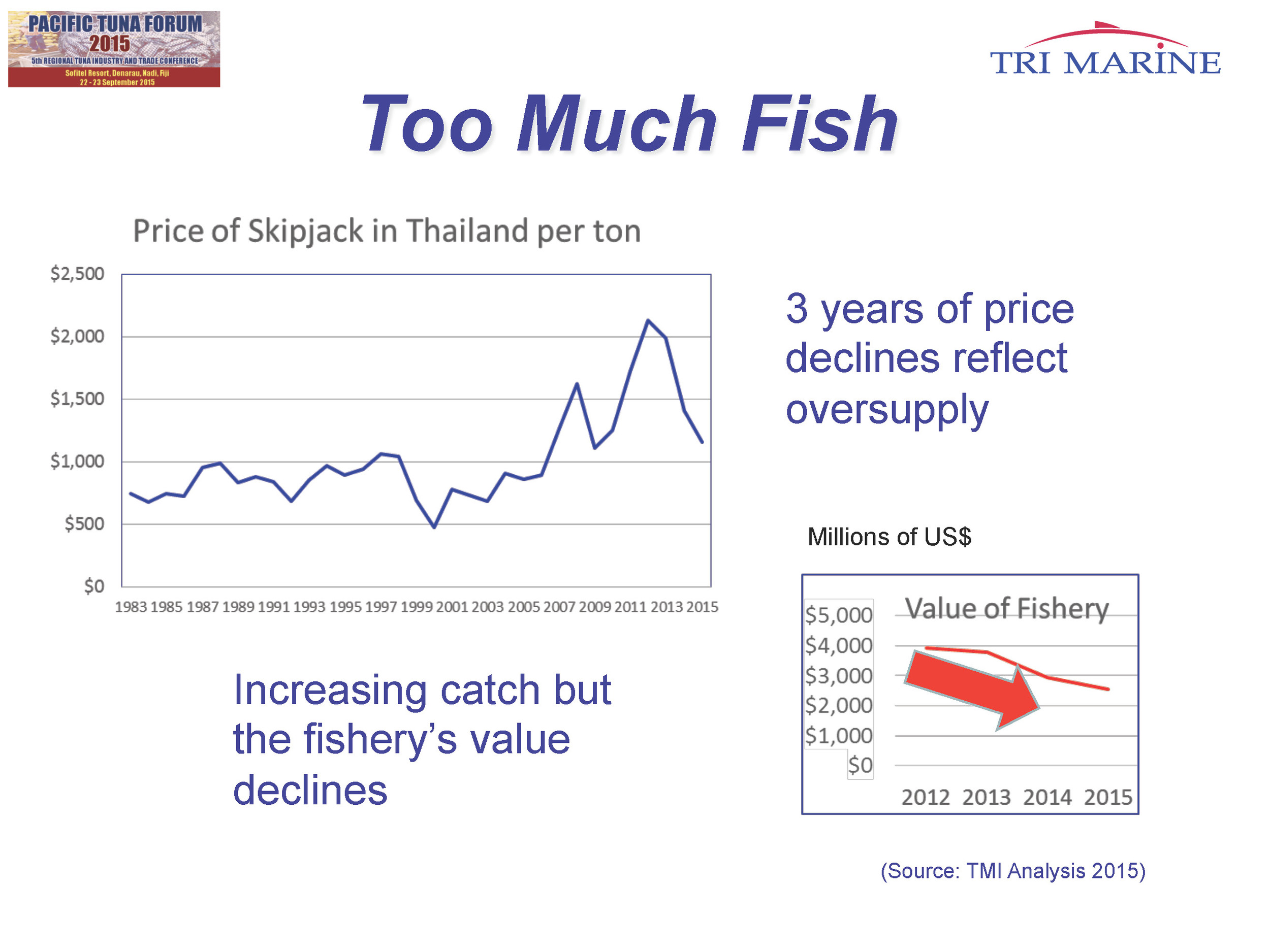

So the commission has adopted a conservation and management measure for a target reference point for skipjack tuna and that is a really fundamental measure on a fundamental stock. It paved the way for more robust and strategic management frameworks and it is a great pay off for the hard work and the leadership that, particularly, the Parties to the Nauru Agreement have put in. They have been working on this for a long time. It has cost them money to get together and talk about it. It has taken a lot of support from SPC, FFA and the PNA office so it is an excellent pay off there. I think it is also significant to note that the final proposal that was adopted was actually a joint proposal between FFA members and Japan. And that is significant because Japan’s concerns about range contraction in the skipjack stock have been a very contentious point of discussions throughout this week so the fact that Japan and FFA members managed to find ways in the text to accommodate those different views about that issue sort of speaks to the maturity of the relationship between Japan and the Pacific Island countries. So, as I say, that was one of our highest priorities and the fact that it has been adopted was really positive.

Secondly the Commission has adopted the work plan on development of harvest strategies and I think I have been through the background to that before but basically what that is useful for now is that it provides guidance to all stakeholders on how the commission intends to develop these management frameworks over the next couple of years and in doing so it mainstreams a lot of the work that is being done on the edges, a lot of work that PNA members have done for their own purposes, that Tokelau Arrangement participants have done on albacore and so on so now it is more a part of the commission.

The third of the highest priorities that we have had success on is the development of a revised compliance monitoring scheme so this is the process that the commission uses to assess the level of implementation and compliance of members, so are they going home and implementing the obligations they take on. This has been an evolving measure over the last couple of years and there are some very significant changes that have been done to it this year. Things like better reflecting the fact that in some cases there are obligations that small island developing states can’t implement because of lack of capacity. So finding a way for the Commission to actually recognise that and actually put in place plans to improve the capacity of the small island developing states so it can comply, rather than it be simply a punitive measure that badges people as non-compliant.

Unfortunately our fourth top priority was the adoption of a target reference point for albacore tuna and we weren’t able to get any movement on that so obviously we are deeply disappointed that such an important stock is going to sort of lag behind a year in terms of the development of a harvest strategy.

Having said that the results of the new stock assessment are very threatening and very different from our previous understanding of the albacore stock. And they talk about relatively significant reductions in catch that are required just to keep the stock where it is at the moment let alone to rebuild it to the level that the Tokelau arrangement participants want to see for reasons of fishery profitability. So in some ways the reluctance of the inability of the distant water fishing nations to sign up to that target reference point even as an interim is understandable but the fact is that this fishery is just so important to those Tokelau arrangement countries that they can’t afford for the management to simply lag because the science has changed or the results ae threatening. So basically what that means is we have got to go back to the drawing board. We will continue our work internally on the development of the catch management scheme under the Tokelau arrangement and we will be using our recommendation for the target reference pint as the basis for that.

We had some very positive and pro-active announcements from the Cook Islands as part of the negotiations indicating their willingness to take the difficult decisions provided it was part of a package of agreements from others as well. So we will just be looking to build on that momentum and work internally.

At the same time, you know, we are calling on the distant water fishing nations to do their home work; to go home and go through some of the detail that they said they weren’t quite comfortable with here and we are looking forward to more discussions at the science committee and at the Commission again next year.

On the albacore fishery tho the Commission has adopted some amendments on the current conservation and management measure that seeks to manage that stock; relatively small improvements but improvements none the less.

The compliance committee has been saying over the last couple of years that because of various ambiguities in the measure. They haven’t been able to adequately assess implementation and compliance. So what we proposed this year and what the commission has agreed to has been some improvements in the data reporting requirements. So flag states will be required to provide a much greater level of detail than they ever have in the past. And that will give us a much better idea on what has happened in the last 10 years or so of the fisheries operations and where it is going from here on in. So, as I say, relatively small improvements but ones that will give us a better picture as to what is going on. In the meantime we have that internal wok going on catch management schemes and so on. So it is great that the other flag states were able to come on board and agree to those measures, because we have been proposing measures year after year since 2010 without success so this is at least a positive sign for the future.

Unfortunately we didn’t gain any traction on our other three second-tier priorities, high priorities. The first one was a proposal to ban transhipment in the four high seas pockets in the convention area and one semi enclosed area between Kiribati, Tuvalu and Tokelau and that is a real shame because these areas are known IUU risks.

Transhipment in those areas is known to be a risk of illegal fishing, in that vessels that are in there are operating under a lower degree of scrutiny than vessels that are operating in the EEZ’s that surround them, they are allowed to undertake transhipment under relatively loose oversight from their flag states and there has been a lot of evidence provided that vessels that are operating in those areas are not operating in accordance with all the rules of the commission. So it is a great shame that other commission members were unable to support that and it is very worrying that these flag states remain far more interested in defending the operational convenience of their vessels rather than putting in place proper management measures and enforcing those management measures.

Equally, we are very frustrated that our proposal on Port State Measures wasn’t accepted. So our proposal was to strengthen the controls that each country uses when foreign vessels come into their ports in terms of the levels of inspection and information and communication sharing. We have worked hard over the last two years to try and develop a measure that is robust and meaningful but also addresses the elements of the FAO Port States measures that a lot of countries don’t like. So there is a global instrument agreed by the FAO on port State measures. FFA members have certain problems with that instrument and other commission members do as well so we have been trying to find the right balance between the elements that we do like out of it and avoiding the issues.

Unfortunately for at least some members we are still not there yet and so partially we are calling on them to tell us what more we can do to the measure to make it acceptable to them but partially also we will have to turn our view inwards now and simply work among ourselves as FFA members on our own measure for port state control because it has been two years now that we have been proposing this and we can’t simply avoid taking the management reforms for our ports just simply because we are waiting for a decision from the commission.

Then, last but by no means least, the commission has again failed to improve on the management of the tropical tuna fisheries and in particular to take additional steps to reduce the fishing mortality on bigeye tuna. The lack of agreement does belie the level of effort that went into it. There was a serious effort on behalf of all embers and particularly led by the chair to get a deal done. And there was an emerging deal that had some potential to get through. Unfortunately where the commission fell down which is nothing new is trying to find the right balance between those countries that have purse seine interest and those countries that have longline interests. And the commission members simply couldn’t find the right balance.

Now this is a particularly important issue for the FFA members and in particular the PNA members because it comes back down to this concept of disproportionate burden; the FAD closures which are one of the main components of the measure transfer what we call a disproportionate burden onto the small island developing states. It means they are suffering a cost that far outweighs the costs that are being borne by other commission members and far outweighs the benefits that they get for the conservation of bigeye tuna. So that is why PNA have been proposing a package of measures to improve the longline measures and to improve the purse seine measures because until you do start to get a better balance between the flow of costs and benefits then it is going to be very, very difficult, well impossible, to talk about further reductions in the purse seine fishery.

The package of measures that the PNA members put on the table at the start of the meeting were used by the chair as the basis for her endeavours to secure an agreement, and as I say, the difference and the divergence between the two groups have meant it was just too much and there is very different perceptions about what is a fair contribution between each fishery depending on which country you talk to. So that is a deeply frustrating situation and what it really highlights, yet again is the fact that the way that the way the WCPFC approaches the management of fisheries needs to be fundamentally reviewed.

The measure that is on the table is the product of negotiations over at least a ten year period and so it contains a real mix of measures; some measures are zone based, like it reflects the vessel day scheme for the regulation of purse seine effort. Other measures are FAD based, like the FAD closures and the FAD set limits which each flag state, Japan, Korea, and Chinese Taipei gets to decide on how they manage their fleet and when you have that system of flag limits superimposed over exclusive economic zones you create lots of anomalies. You create the need for things like SIDs exemptions, because small island developing states as flag states, they are only just building their fleets now so they don’t have 50 years of catch history to fall back on like the developed fleets so it just doesn’t work. So we need to be doing things like moving towards establishing rights that are zonal rather than flag-based. This is nothing new. It is exactly what the vessel day scheme is. It is exactly what the longline vessel day scheme is and the emerging catch management scheme under the Tokelau arrangement for albacore. So these are the types of more strategic discussions that need to be happening now. It is quite clear that simply the concept of amending this paragraph is not going to work. We have tried it the last two years without any movement at all so now we need to step back and say ‘how are we going to manage these fisheries?’

The commission has agreed that a new strategic plan will be developed for the WCPFC and we think that is an excellent idea and we think that will be a really good vehicle for the WCPFC to have some of this higher level debate, and to have it not focussed on the context of how to manage bigeye tuna, to have it as a more strategic thing about ‘how should we be going about our job?’

Bigeye stocks

It is always very difficult for the science community to predict the outcomes of any management measure, particularly one as complicated as this. It has got so many moving parts. So many choices that different countries can make on how they do things but the modelling that SPC has done that under any combination of the options that are available to all the countries the measure is not going to achieve its objectives. Its objectives are to remove the overfishing of the bigeye; so to reduce the fishing mortality to the levels which will produce maximum sustainable yield.

Having said that it does clearly show that the measure is having a positive impact; it has reduced FAD sets, it has reduced longline catches and it has improved the amount of information that is available. The modelling also suggests that the measures that are in place right now will contribute to increasing the spawning biomass so as you say the spawning biomass at the moment is at 16 per cent of unfished levels and the measure that is in place will assist that to rebuild. The issue is ‘does it do so strongly enough?’ and the answer clearly is ‘no’. So in terms of overall effectiveness what is really needed is a relatively minor series of improvements but unfortunately because of the evolution of the measure those minor improvements are turning out to be impossible to agree to. So I think overall, the outlook in the short-term is not overly pessimistic. We will see a stock improvement but it is not a stock improvement anyone would go boasting about. So the commission really does have its work cut out for it to say ‘well, this measure expires by 2017. By this time we have to have a really good idea on how we are going to fix this thing.

There are programs in the wings that will contribute to this. The PNA members are commencing a FAD charging trial as of 1st January and what this endeavours to do is use market forces to regulate fishing behaviour. So any day you go fishing and you set on a FAD you pay an extra fee basically and so basically what that does is force the vessel operator to choose ‘is it worth me setting on this FAD? Am I going to catch that much more fish and earn that much more money, that makes it worthwhile paying this fee?’ And eventually over time we see these sorts of market based measures as replacing some of the regulatory measures so we’ve got a four month FAD closure in place at the moment at some stage we hope it can go down to a 3 month FAD closure because FAD sets generally are being reduced by this economic