Lots going in the media in regards the negotiations for a treaty on high seas biodiversity beginning this week at the UN in New York, (under Resolution 72/249) for a new international legally binding instrument (ILBI or treaty) under the UNCLOS for the conservation and sustainable development of marine biological diversity in areas beyond national jurisdiction (ABNJ) also know as High Seas. This is a series of four two-week meetings between now and early 2020. The final treaty will be the third “implementing agreement” under UNCLOS.

I was trying to explain to my non-fisheries friends (and my kids) the issues around fishing in the High Seas, so I decided to dive a bit deeper and understand the whole picture for my self, since I have 6 hrs in an airport on my way to a job in Kiritimati, and here is the result.

Disclaimer: I’m not a legal or institutional fisheries expert, all the opposite! Im the 1st to admit I’m just a fisherman with a laptop, and jsu based my self on lots or reading and some references that are at the end of the post. So if you (reader) find mistakes please let me know.

UNCLOS (1982 UN Convention on the Law Of the Sea)

UNCLOS defines and establishes the rights and responsibilities of countries related to their use of ocean resources—including environmental impact, management of fisheries, and business practices. Three legal tiers govern the ocean—a territorial approach, a flag state approach, and a port authority approach. (I wrote enough about PSM in the past)

The territorial approach establishes zones that delineate the extent of sovereignty and each country’s jurisdiction over ocean resources. These zones allow countries to exploit, manage, and protect their marine resources. The three essential tiers of ocean zones are: territorial water, contiguous zone, and EEZs.

Territorial waters extend out 12 nautical miles and countries have full sovereignty over this area, wherein all national laws and regulations apply.

The contiguous zone starts where the territorial zone ends and continues 12 nautical miles further. Countries have the power to enforce certain domestic laws pertaining to customs, taxation, immigration, and pollution.

Beyond the territorial waters, and including the contiguous zone, is the EEZ, which extends outward 200 nautical miles. An EEZ assigns control of the economic resources to the coastal country, including rights to fishing, mining, and oil exploration (these last 2 can go to 350 miles)

In response to the limits of the territorial approach, the international community established requirements for vessels to be marked with the flag of its home country. Under these requirements, each flagged vessel is subject to the laws of the country where it is registered, even outside national territory. Moreover, the flag state is responsible for enforcing regulations over such vessels, including both international and national maritime laws.

In addition to being under the jurisdiction of a flag state, being flagged also provides the vessel with protection from other states. If a stateless vessel is encountered by the authorities of a state, it risks being seized by that state, and the adjudication process varies country to country.

Beyond those waters, the international community has established a governing system of regional fishing bodies, which includes a subset of RFMOs mandated to “adopt conservation and management measures for fishing on the high sea.”

RFMOS (Regional fisheries management organisations)

Amongst UNCLOS requirements are the duty to conserve the living marine resources of the high seas and to cooperate with relevant coastal states and other high seas fishing states in the conservation and management of stocks of fish that occur both within areas of national jurisdiction and on the high seas – primarily straddling and highly migratory fish stocks.

Moreover, UNCLOS contains obligations to protect and preserve the marine environment and requires that flag States exercise effective control over their vessels operating in high seas areas. UNFSA elaborated on the general provisions of UNCLOS and established RFMOs as the institutions charged with managing high seas fisheries.

RFMOs are assumed to provide a forum through which States will cooperate to achieve and enforce conservation objectives, both on the high seas and in areas under national jurisdiction. Their responsibilities include assessing the status of fish stocks of commercial value within their area of jurisdiction; setting limits on catch quantities and the number of vessels allowed to fish; regulating indirectly via CMMs (Conservations and Management Measures) that apply the types of gear that can be used, to species of interest, to reporting requirements, to interaction with birds, and thousand more issues… this CMMs then need to be incorporated into regulation by the member countries, and implemented by the flag states and slowly now more by coastal and port state when the offences are under their jurisdiction.

RFMOs vary widely in their effectiveness and many suffer from shortcomings in their governance and management structures, and while criticised sometimes as toothless tigers, that is a bit unfair, since they are member-driven organisations. So if fingers are to be pointed... is to the members and not the just the body.

The regulations adopted by RFMOs only bind those nations that are Parties to the RFMO. Non-parties are free to do as they please, often with minimal repercussions; their catch, if in contravention of the RFMO regulations, would be considered unregulated. While the offending non-Party vessels and countries are often subject to port- and market-access restrictions, fishing on the high seas in the waters managed by an RFMO is not a crime.

Effective RFMO decision-making is often undermined by one or a handful of Parties. Many RFMOs operate on consensus-based decision-making, whether as a formal requirement or as standard practice; thus a conflict of interest, or a lack of political commitment by just one member, can prevent the adoption of meaningful regulations.

Where RFMOs do not require consensus but can adopt regulations on the basis of a vote by a majority or qualified majority of the members, most also allow members to ‘opt out’ of regulations they don’t wish to accept or be bound by.

Moreover, many RFMOs lack transparency in important respects, key decisions are often made in closed sessions – without the need for Parties to justify positions or with little accountability to the civil societies back home.

Most RFMO member States have a direct economic interest in the fisheries managed by that organisation. They are often reluctant to accept new members and allocate them catch allocations. And many of these catch allocations are decided as result of stock assessments, which are in substantial part informed by flag state reporting, which many don't really do or do intentionally wrong, so it becomes a bit a vicious circle.

Also RFMOs tend to focus their management on a single species or handful of species of commercial value, which leaves the impact of fishing on many non-commercial species and the ecosystem effectively unregulated. However, despite being mandated to establish measures with respect to non-target species, associated and dependent species, and species belonging to the same ecosystem on the basis of the precautionary approach and ecosystem approach, RFMOs tend to fail short in consider impacts on the broader ecosystems affected by the fisheries they regulate.

Communication and coordination between adjacent RFMOs are complex, even if many DWFN are members of many, they sometimes have divergent policies for each one. Furthermore, each RFMO operates independently, with its own staff and funding. And there is a great disparity in funding levels and corresponding capacity among them. Roughly US$ 30 million is spent annually on fisheries management in the main 11 RFMOs, with most of it directed to the five main tuna RFMOs. These funding figures have dramatic contrast when compared to the approximately US$ 35 billion spent annually on global fishing subsidies, and even more so considering the consumer end value of the tuna industry (around 8 billion USD) or the estimates of value of IUU fishing (i.e. over 600 million USD in the the area of the WCPFC alone)

Beyond managing shared stocks, RFMOs could benefit from greater communication, to ensure they share lessons and avoid repeating mistakes; some RFMOs are much younger than others and can benefit from their greater experience. There have been important improvements in recent years, for example, the Contracting Parties to the five main tuna RFMOs have established the Kobe process in order to share information on issues of mutual concern and facilitate better coordination amongst themselves.

In addition, a number of RFMOs (e.g. NAFO and NEAFC; SEAFO and CCAMLR) share information on IUU fishing and IUU vessel blacklists, while the Secretariats of the major RFMOs have held meetings in conjunction with the biennial meetings of the FAO Committee on Fisheries since 1999.

Is also fair to say that the issues with a lack of coordination extend beyond fisheries. Other regional or global structures often exist in the same ocean space as RFMOs but manage other sectors. For example, UNEP’s Regional Seas Programmes address topics such as marine health and pollution; the International Maritime Organization (IMO) addresses shipping and potential discharges; and the International Seabed Authority (ISA) covers seabed mining. The actions and management decisions of these various groups may affect the marine environment and its fish stocks but coordination across the sectors is largely absent.

UN Fish Stock Agreement (UNFSA)

Arguably the most important of the international fisheries agreements the UNFSA, establishes a range of obligations related to the conservation and management of fisheries on the high seas, which build on the more general provisions of UNCLOS18. Articles 5 and 6 of the UNFSA oblige States to:

assess the impacts of fishing on target stocks and species associated with or dependent upon the target stocks, and prevent overfishing

minimise bycatch, waste and discards, and impacts on non-target species

protect biodiversity in the marine environment

collect and share accurate and timely data on catch and bycatch and areas fished

apply the precautionary approach, particularly where scientific information is poor

protect habitats of special concern.

The UNFSA obliges States to ensure the compatibility of measures for the management of straddling and highly migratory fish stocks adopted by coastal States within EEZs and RFMOs on the high seas. With regard to the duties of flag States fishing on the high seas, the UNFSA establishes a series of obligations in relation to compliance and enforcement (Articles 18–22).

Amongst these is a requirement that the flag State exercises effective enforcement capabilities over fishing vessels flying its flag, so as to ensure compliance with applicable regional conservation and management measures irrespective of where violations occur.

The flag State is also required to investigate immediately and fully any alleged violation of sub-regional or regional conservation and management measures and to report promptly on the progress and outcome of the investigation to the State alleging the violation and the relevant sub-regional or regional organisation or arrangement. In addition, the flag State must require any vessel flying its flag to give information to the investigating authority and, where sufficient evidence is available in respect of an alleged violation, refer the case to its authorities with a view to instituting proceedings without delay.

UNFSA Article 21 establishes a list of ‘serious’ violations requiring enforcement action by the flag State and obligates the flag State to, where appropriate, detain the vessel concerned and ensure that, where it has been established that a vessel has been involved in the commission of a serious violation, the vessel does not engage in fishing operations on the high seas until such time as all outstanding sanctions imposed by the flag State in respect of the violation have been complied with.

In language similar to UNCLOS Article 217.8, UNFSA Article 19.2 requires the flag State to impose sanctions that are “adequate in severity to be effective in securing compliance and to discourage violations wherever they occur and shall deprive offenders of the benefits accruing from their illegal activities”. There have been numerous cases where vessels identified by an RFMO as having engaged in IUU fishing have reflagged and continued fishing without effective action taken by the flag State concerned to penalise and prevent the vessel from continuing as an IUU fisher on the high seas.

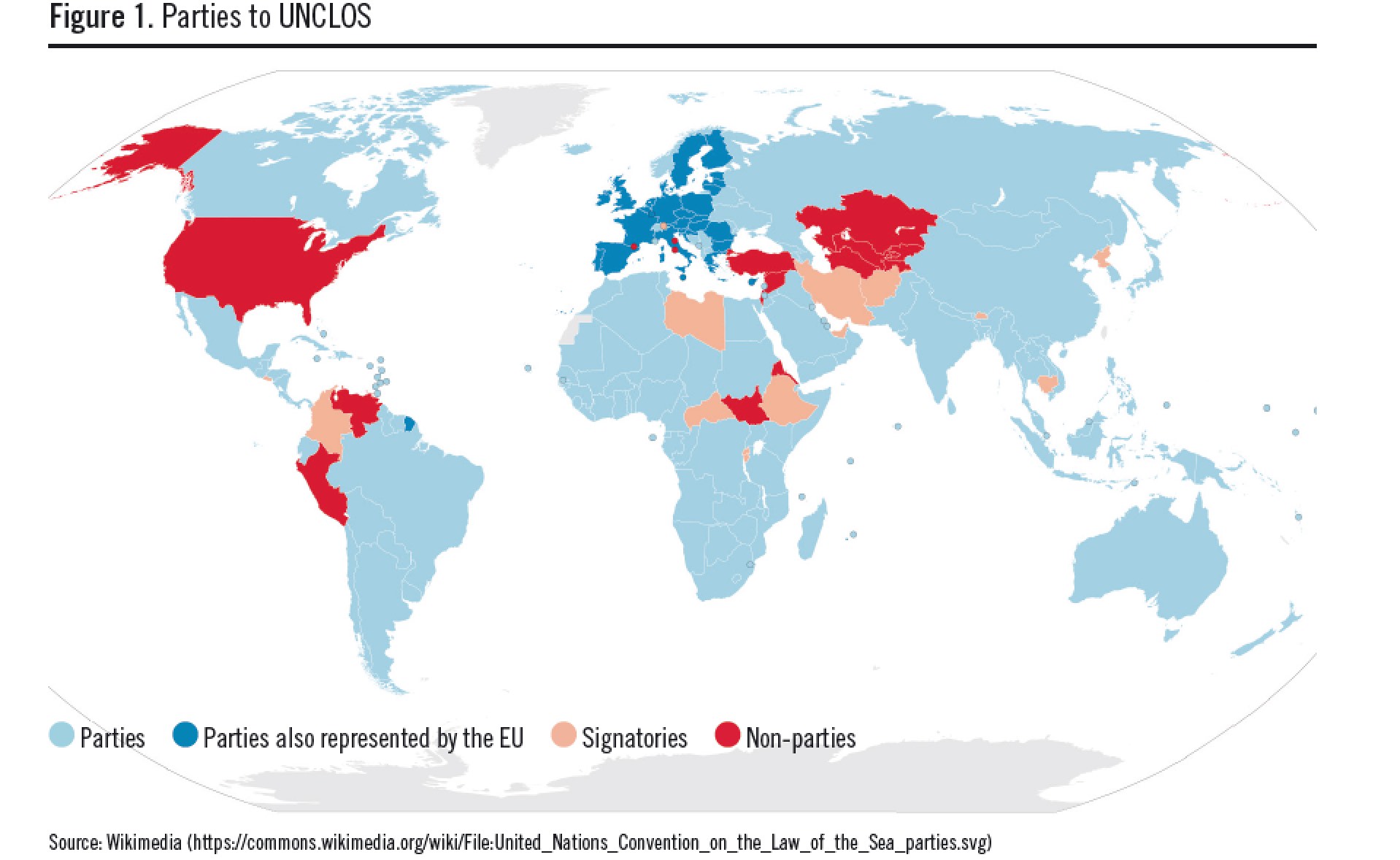

The UNFSA has been ratified by 83 states and the European Union, which includes most high seas fishing nations; however, important exceptions remain, e.g. China, Chile and Mexico. While several provisions of the UNFSA, primarily the compatibility and high seas boarding and inspection provisions, have been cited by a number of States as a reason for not having ratified the UNFSA, the conservation provisions of the UNFSA (Articles 5 and 6) are not in dispute.

The relatively low number of ratifications is particularly striking when compared to the 168 ratifications which UNCLOS has (which includes 146 UN Member States, the EU, Cook Islands, Niue and Palestine). An additional three UN member states have signed, but not ratified the agreement) Many nations have not ratified the UNFSA because they do not want to be bound by its more prescriptive requirements for fisheries management.

The development of the Agreement was in recognition of the fact that the regime established by UNCLOS was inadequate to deal with the continued depletion of the world’s fish stocks, particularly straddling and high seas stocks. Importantly, however, the UNFSA does not seek to impose any additional requirements on Parties to UNCLOS, in fact it is first and foremost an agreement for the purpose of implementing the provisions of UNCLOS. While individual countries may consider it deficient, it cannot reach its full potential unless the most important coastal, fishing and flag States are parties to it, and implement it effectively.

FAO Code of Conduct

The 1995 FAO Code of Conduct for Responsible Fisheries is one of the most important soft law instruments. Its purpose is to set international standards and norms for the development, management and utilisation of fisheries and aquaculture resources, in areas beyond and within national jurisdiction. As such it has been described as a “global ethic for the conduct of fisheries”.

The Code has 10 objectives through which it promotes responsible fisheries by establishing scientifically based management decisions, which take into account all relevant biological, technological, economic, social, environmental and commercial aspects; establishes responsibilities for flag and port States; and recognises the importance of fisheries to food security, nutrition, and ecosystem health. There is a particular emphasis on conservation of living aquatic resources and their environments. It intended to serve as guidance for the development of national legislation. The conservation and management provisions of the UNFSA (Articles 5 and 6) and the FAO Code of Conduct (Articles 6 and 7)are very similar and in many cases contain identical wording.

The FAO Compliance Agreement forms an integral part of the Code and is referenced in Article 1. The Compliance Agreement elements remain binding but overall the Code is a voluntary agreement. It relies on the goodwill of Parties to enact and abide by its recommendations. Unfortunately, it seems that this does not happen across the board.

The FAO Code of Conduct reinforces the universality of the conservation provisions in the UNFSA and thus, together with the UNFSA provisions, should serve as the ‘international minimum standard’ for the management of fisheries on the high seas and be fully reflected in the basic convention texts and regulations adopted by RFMOs to manage fisheries on the high seas.

FAO Compliance Agreement

The purpose of the 1993 FAO Agreement to Promote Compliance with International Conservation and Management Measures by Fishing Vessels on the High Seas (Compliance Agreement) is to provide an instrument for countries to take effective action, consistent with international law, to ensure compliance with applicable international conservation and management measures for living marine resources of the high seas. Adopted in 1993 and entering into force in 2003, the Compliance Agreement has been ratified by 48 nations plus the EU.

This instrument was negotiated to address the circumvention of international fisheries regulations by ‘re-flagging’ vessels to the flags of States that are unable or unwilling to enforce such conservation and management measures. The main obligation is for a Party to exercise responsibility over vessels flying its flag, and to provide information to a global record of fishing vessels (which became known as the High Seas Vessels Authorization Record – HSVAR).

But what about capacity development?

Not all nations possess the same capacity to enforce the international or regional rules and regulations they have adopted. In an FAO survey in the mid-2000s more than one-half of the 64 self-reporting countries said their ability to control the activities of their flagged vessels on the high seas was ineffective or inefficient.

Developing countries face a huge number of often competing pressures that limit their ability to make progress in fisheries management. Fisheries management requires a robust legal system, political will to develop binding management arrangements, and a justice system capable of successfully prosecuting offenders. There are numerous studies that show a high degree of correlation between weak governance and IUU fishing.

Despite the millions of dollars that have been provided in direct aid to the fisheries sectors in developing countries and the capacity development funds established under specific treaties, there have not been substantial improvements in the high seas fisheries management. Neither has this funding, by and large, enabled developing countries to take a meaningful place in international management arrangements and a share of high seas resources.

The 1993 FAO Compliance Agreement was the first international fisheries instrument to address capacity building directly. However, the 1995 UN Fish Stocks Agreement devoted an entire section to capacity development, including the establishment of an assistance fund to address the requirements of developing countries. Known as the Part VII Assistance Fund, it has operated successfully since its inception in 2005. Between 2005 and 2010 the fund amounted to just under US$ 1 million. The assistance fund has facilitated increased participation by developing countries in regional and international meetings and also enabled technical work and capacity development that might have not been undertaken if such activities had been dependent on funding from other sources.

The FAO has channelled a significant amount of resources to support the implementation of the 1995 FAO Code of Conduct across the world. Funding has come from the FAO Regular Programme and non-FAO resources and was managed by a dedicated programme within the FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture Department. In 2000 the programme was replaced by the more elaborate, better-funded and more flexible FishCode Programme. A significant amount of FishCode Programme funding has been devoted to helping countries implement programmes to combat IUU fishing, including capacity development for the implementation of port State measures.

Other international agreements also have provisions for capacity development (e.g. PSMA and the International Plan of Action to Prevent, Deter and Eliminate IUU fishing [IPOA-IUU]), as do individual RFMOs and individual States.

The fundamental principles and legal obligations (e.g. the precautionary approach, ecosystem approach, etc.) that could lead to sustainable fisheries management, are already contained in many of the binding and non-binding fisheries agreements, and in the UNFSA in particular. What is needed is an effective and uniform application of these principles and obligations in practice.

And hopefully, this new negotiation can help there… but that is a big if…

Personally, after explaining it to my kids, I take away their suggestion: if it is that the high seas don't belong to anyone, but they belong to everyone, in that case, if anyone wants to fish there, it should have everyone’s else permission. That would be fair, right?

Main sources: here, here and here