Climate change is a really complex issue and is difficult to take perspective of what are the issues and "who" is to blame (like if that is to help).

This little video by "The Economist" ads to that understanding and discussion.

Climate change is a really complex issue and is difficult to take perspective of what are the issues and "who" is to blame (like if that is to help).

This little video by "The Economist" ads to that understanding and discussion.

Recently published, a new collection of research designed to inform decision makers, including governments and investors, on effective ocean and coastal resource management strategies to maximize economic, conservation and societal benefits.

The research demonstrates how governance and management reform can reduce poverty while achieving economic gains, increasing food production, replenishing fish and conserving ocean health for future generations. This is especially true in the case of wild capture fisheries.

I would be presenting some of the research in the blog, but is always better to go to the source (as good scientist I’m) but if you want a digest, then stay here ☺

This came out in May, and is supported by a “stars” filled group of fisheries scientists… most analyses of fisheries often demonstrate the potential biological, economic, and social benefits of fisheries recovery, but few studies have incorporated the costs associated with the design and implementation of the management systems needed to achieve recovery.

Using available data and anecdotes they suggest that the current cost of fishery management may be quite substantial and that additional costs arising from major upgrades in management could be prohibitive in some countries. Their analysis focused on OC (Output Controls) and CS (Catch Shares - Quotas) Scenarios of Management measure and compared them a Business as Usual Scenario

A careful analysis comparing the country-level benefits of fishery management improvements to the additional costs of doing so has never been undertaken. Therefore, a study focusing on the current and incremental costs of fishery management upgrades could have important implications for policy design to efficiently rebuild global fisheries.

This analysis has three objectives. The first is to estimate the current cost of managing fisheries in the top fishing countries of the world. The second is to estimate, for a range of alternative management approaches, the concomitant change in cost, also at the country level. Finally, they combine these cost estimates with recent estimates of the economic benefits of fishery recovery to arrive at a cost-benefit calculation of improved fishery management around the world.

This comparison determines if the expected economic benefits of a suite of fishery management reforms are greater than the management costs associated with those reforms. The analysis is decidedly practical: our goal is to derive ballpark estimates of these values to ultimately inform the question of whether the potential benefits can justify the likely increase in management costs.

Methodology

There are five major steps to completing this analysis. First, they estimate the cost of managing fisheries for all major fishing countries in the world and standardize by the cost per metric tonne (MT). This step is accomplished by developing a cost database including as many countries as possible and then imputing cost, based on the available data, for countries with limited data. They then focus on the 25 countries with largest fish catch.

Second, They categorize the landings in each country by management type. The third and fourth steps are developing and implementing a model of incremental management cost parameterized with cost data, fishery management data, and a survey of global fishery management experts to estimate the future costs of alternative management interventions using.

Finally, using projected profits in the year 2050 associated with different management interventions, they compare the economic benefits of management reform with the estimated costs associated with the new management in each country.

Results

They find substantial variation in current management costs across countries (approximately an order of magnitude difference in management cost per MT) and that incremental costs of upgrading fishery management can be quite substantial (in some countries, this could involve a doubling or tripling of management cost). Despite these results, our overall finding is that in every country examined, the benefits of reform substantially outweigh the incremental costs in management. This result holds across a wide range of assumptions and is consistent with empirical data, new case studies, and ad hoc interviews conducted with fishery managers in countries that have already undergone these welfare-improving transitions.

OC and CS Scenarios Compared to BAU, 2050

Figures below shows the incremental cost vs. the incremental benefit of fishery management reform, where each country is represented by a single point. The size of the point indicates the size of the fishing sector in that country measured in total harvest (in MT) for 2012. Therefore, larger dots represent counties with higher annual landings in 2012. The top panels provide results for CS vs. BAU and the bottom panels provide results for OC vs. BAU.

Difference between future profits and management costs: CS Scenario and OC Scenario compared to BAU. Benefit-cost-ratios are capped at 10 in the figures on the right.

Difference between future profits and management costs: CS Scenario and OC Scenario compared to BAU. Benefit-cost-ratios are capped at 10 in the figures on the right.

Three results immediately pop out. The first is that when considering reforming all fisheries in a country to some form of CS, we find that the cumulative benefits always exceed the costs (all dots are above the 1:1 line on the top left panel and all benefit cost ratios exceed 1.0 on the top right panel). Indeed, the benefit cost ratios range from just over 1.0 up to 82 or more, averaging at about 29. The global benefit cost ratio average for catch share management is 34. These results are at the country level and do not necessarily imply that the benefits of switching to catch share management will outweigh the costs in each fishery. Instead, this result compares the aggregate benefits of moving to CS against the aggregate costs of doing so.

The second result is that the large fishing countries tend to also have the largest benefit cost ratios – it turns out that the larger a country’s catch, the more it stands to gain from aggressive fishery management reforms.

The third result is that while the numerical results are somewhat muted when moving from BAU to OC, most countries would still benefit from such a shift. The global cost of managing all fisheries in our database under catch share management in 2050 is about USD 11.09 billion, which is not quite double the global cost of BAU (USD 6.21 billion) and 2012 current global management costs (USD 5.76 billion).

Discussion

Two interpretations emerge from this study: First, while adopting effective catch shares is likely to entail the largest incremental increases in management cost, it is also likely to lead to even more significant increases in economic rent or profit. In fact, expert opinion suggests that depending on how well fisheries are already managed, the cost of switching to catch share management might even lower costs relative to BAU, which would further strengthen our main results. If some of that increase in profit can be captured to pay for the change in management cost (indeed, only a small fraction of it would be required in most countries), then the policy reform would be win-win.

A key question that comes up when considering management costs is who should pay. It has been argued because the fishing industry benefits from management services, it should pay the costs associated with that management. Generally, taxpayers end up paying for these services, which are in turn provided by the government.

Importantly, the benefits depicted in these results do not reflect individual fisheries, but the generalized benefits at the national level. Specific fisheries might benefit differently from management changes, and effective catch shares will surely require careful design tailored to each fishery.

In addition, while this study suggests that those directly employed by the fishing industry could experience an increase in profits with a shift from less effective management to catch shares, and to a lesser extent, strong output controls, it does not investigate the implications of management reform down the supply chain. The value of this sector could potentially decrease with management that requires decreases in harvests. More research is needed to determine the economic implications of improved management on other related sectors.

The finding that adopting OC is still beneficial, but not as beneficial as adopting CS, is not too surprising, particularly given our assumption that securing long-run economic profit is still possible under OC. While output controls alone can be effectively implemented to regulate catch and achieve conservation objectives, there is a strong theoretical argument that they cannot ensure significant long-run profits, because rents will be dissipated by excessive effort on unregulated margins.

Thus, they regard the OC scenario as an intermediate case between open access and fully rent-capturing catch shares. As such, the profit upside from OC will always be lower than the profit upside from CS. While it is also true that our results suggest lower management costs under OC (than CS), they are not sufficiently low to make OC more attractive than CS.

Future work

There are a number of ways in which this study could be built upon to further examine the relationship between costs and fisheries management. First, while this study focused on the annual cost of management after management reform has been implemented, studies and interviews indicate that transition costs can be significant. During the transition period, the reform is designed and planned. This stage can be labor intensive and take a substantial amount of time, thus incurring significant fixed costs. In addition, it may require expensive research efforts to guide reform design. Including this expense would capture a more comprehensive cost of fisheries management.

Second, future studies could expand on this work by developing a more precise model for determining changes in management cost, for example by incorporating complexities in rules and regulations such as bycatch regulations, limits on days at sea, gear restrictions, and required reporting and analysis likely to influence the costs of administration, research, and enforcement services.

Finally, while the country-level approach used in the current study is useful for making decisions at the national level, a fishery level-approach might provide key insights for managers working on the reform of individual fisheries. This approach would require fishery-level data on the cost associated with management attributes specific to fishery type. Importantly, improved data on the cost of managing fisheries at both the country and fishery level would facilitate more precise analyses.

Conclusion

The research highlighted here demonstrates that when governments implement and enforce strong policies and regulations to manage their fisheries sustainably, the benefits are mutually reinforcing: fish production increases; economic profits rise; and fish stocks recover and rebuild. The path to sustainable fisheries will require not only reform by government, but also accompanying practices such as an improved business environment, increased transparency, and sound science and careful monitoring. Collectively, these practices create a synergy that helps enable the transition to sustainable fisheries management.

One of the remaining challenges is determining how best to finance the comprehensive costs of reform, particularly during the transition period. We believe there are emerging opportunities for all sectors to contribute to the transition to sustainable management, from the private sector and public finance playing an innovative role in financing the transition, to the research community providing critical and timely data as well as innovative technologies that can enable smart policy decisions.

The rewards of sustainable management have never been higher—and the costs of inaction have never been more clear—in unlocking the underlying potential of global fisheries.

I get asked often about this issue… A truly complicated topic I know very little about (and I believe not many people do really know a lot about it). Its really complex and truly interesting, since it adds a full new set of variables to fisheries management, which is per se already multifaceted.

A few years ago, SPC published an interesting book (Vulnerability of Tropical Pacific Fisheries and Aquaculture to Climate Change), that in my opinion still leads the pack and what is (could?) be happening.

The build-up of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere is acting in two major ways that are ultimately expected to affect fisheries and aquaculture in the tropical Pacific.

First, the accumulation of greenhouse gases is trapping more of the heat that would normally escape from the Earth, leading to an overall increase in global surface Temperature. The oceans have absorbed almost 80% of the additional heat, acting as a buffer against more rapid atmospheric warming. However, the continued uptake of this extra heat has wide-ranging implications for marine resources.

Generalised effects of increased greenhouse gases on oceanic and coastal ecosystems in the tropical Pacific

Thermal expansion of the ocean, together with melting of land ice, is resulting in rising sea levels. Increases in ocean temperatures are also changing the strength and direction of currents, and making surface waters more stable, reducing vertical mixing and the availability of nutrients in the upper layer of the ocean. Reductions in the supply of nutrients usually limit the primary production at the base of the food chains that support fisheries.

Warmer oceans also cause changes in atmospheric circulation patterns, giving rise to regional changes in climate. In the tropical Pacific, greater evaporation and moisture availability are expected, leading to an intensification of the hydrological cycle, and a pole ward expansion and possible slow down of the Hadley circulation. As a result, rainfall is projected to increase in tropical areas of the Pacific and decrease in subtropical areas, although there is still considerable uncertainty about the regional pattern of projected changes. There is also the possibility that warmer conditions may result in more intense cyclones and storms, resulting in rougher seas, more powerful waves and greater physical disturbance of coastal environments.

The second way that increasing greenhouse gases are expected to affect fisheries and aquaculture is through changes to oceanic concentrations of CO2 and the resulting effect on ocean acidity. The ocean has absorbed more than 30% of human CO2 emissions since the beginning of the industrial revolution and it is now more acidic than at any time during the last 800,000 years.

This effect is largely independent of global warming but also has grave consequences for marine ecosystems. The dissolved CO2 reacts with sea water to form weak carbonic acid, which reduces the availability of dissolved carbonate required by many marine calcifying organisms to build their shells or skeletons.

There is serious concern that continued emissions of CO2 will drive sufficient gas into the sea to cause under-saturation of carbonate in some areas of the ocean this century. Where this happens, the environment will favour dissolution rather than formation of carbonate shells and skeletons.

Nature of effects of climate change on fisheries and aquaculture worldwide

The basis of tuna production in the Western and Central Pacific Ocean, and the main methods used to harvest tuna

We already know that variations in climate on time scales of years to decades can cause significant changes in fisheries production. For example, catches of Peruvian anchovies have varied between < 100,000 tonnes and > 13 million tonnes since 1970 as a result of changes in ENSO46,47. The different phases of the ENSO cycle also determine the distribution of skipjack tuna in the Western and Central Pacific Ocean – the fish move further east during El Niño events and further west during La Niña episodes ( I wrote about this here and here)

Over and above normal year-to-year variations, longer-term changes in physical oceanography and biology, known as regime shifts, can have major consequences for the species composition and productivity of fisheries. Some heavily fished stocks have collapsed due to the additive effects of environmental and fishing stresses.

However, the effects of such changes in climate have not always been negative. For example, a period of ocean warming around Greenland starting in 1925 resulted in a northern extension in the range of cod by > 1000 km and the creation of an international fishery of up to > 400,000 tonnes per year.

Questions abound for fisheries management. Will the species that currently support substantial harvests still be available as climate change continues? If not, which types of species are most likely to replace them? For those species that continue to support fisheries, will climate change reduce the capacity for replenishment and production, and increase the risk of overfishing? How should managers and policymakers respond to the projected changes to maintain sustainable benefits from fisheries? How will fishers perceive and react to the risks associated with projected changes? Will fishing at sea become more hazardous? How much will it cost to adapt?

Potential impact of climate change on fisheries and aquaculture in the tropical Pacific

The range of coastal fisheries activities in the tropical Pacific, and the habitats that support them.

All fisheries and aquaculture activities in the region are likely to be affected by climate change. The distribution and abundance of tuna, which dominate oceanic fisheries and are the mainstay of the economies of some smaller PICTs1, are influenced largely by water temperature and the availability of nutrients.

The coastal fisheries that currently provide much of the animal protein for Pacific islanders14, and the contribution of aquaculture to the economies of French Polynesia and Cook Islands, are based largely on coral reef habitats. These habitats are threatened by changes to water temperature, acidification of the ocean and sea-level rise, and possibly more severe cyclones and storms.

The freshwater fisheries of PNG have evolved in a climate of heavy rainfall and any major alterations in precipitation can be expected to change the nature of these resources, on which hundreds of thousands of people rely.

Preliminary analysis has already identified the following possible effects of climate change on fisheries and aquaculture production in the tropical Pacific from climate change:

Changes to the distribution and abundance of tuna: Alterations in ocean temperatures and currents and the food chains that support tuna, are projected to affect the location and abundance of tuna species21,48. In particular, the concentrations of skipjack and bigeye tuna are likely to be located further east than in the past. This has implications for the long-term management of the region’s tuna resources, and for the development and profitability of national industrial fishing fleets and canneries in the western Pacific.

Decline in coral reefs and coastal fisheries: Rising sea surface temperatures and more acidic oceans are projected to have direct impacts on coral reefs and the habitats and food webs they provide for reef fish and invertebrates. Degraded coral reefs are likely to support different types of fish and lower yields of some species. Reduced catches of reef-associated fish will widen the expected gap between the availability of fish and the protein needed for food security.

Difficulties in developing aquaculture: Changing patterns of rainfall and more intense storms could flood aquaculture ponds more regularly in some places, and make small pond farming for food security impractical in others due to more frequent droughts. There could also be higher financial risks associated with coastal aquaculture as a result of (1) greater damage to infrastructure and equipment from rising sea levels and the possibility of more severe cyclones and storms; and (2) the effects of higher water temperatures, ocean acidification, reduced salinity and increased incidence of disease on the growth and survival of shrimp, pearl oysters, seaweed and ornamental specimens90.

Increased operating costs: Projections that cyclones and storms could possibly become progressively more intense would involve increased risk of damage to shore-based facilities and fleets for domestic tuna fishing, and processing operations. Fleets operating within the cyclone belt may need to be upgraded to provide improved safety at sea. Rising sea level may eventually make many existing wharfs and shore-based facilities unusable. Taken together, increased costs associated with repairing and relocating shore-based facilities, and addressing increased risks to occupational health and safety for fishers, may affect the profitability of domestic fishing operations. Such increased costs will need to be taken into account by PICTs when planning the optimum mix of developing local industries for tuna and providing continued access for DWFNs.

Reality is that the main findings are mixed – there are likely to be winners and losers – underscores the importance of this vulnerability assessment. Practical adaptations, policies and investments are now needed to reduce the threats of climate change to the many fisheries and aquaculture activities that are part of the economic and social fabric of the region. Adaptations, policies and investments are also needed to capitalise on the opportunities.

Otherwise we will keep running behind the ball (as usual)… unfortunately I don’t see that happening.

Fish aggregating devices (FADs) are artificial floating objects, specifically constructed to attract pelagic fish. Typically, they consist of a floating raft, submerged synthetic netting. Many this days have a “marker” of a satellite buoy that allows a fishing vessel to return to a specific location. They can be anchored or drifting ones, and they are as many design types as people deploying them!

Many fish species naturally congregate near objects floating in the ocean, a fact that is the basis of FADs existence. How they work still debated, but here is a good talk about then.

FADs have become widely adopted as a means of improving fisheries production. In most cases, the effects of FADs—both positive and negative—are not monitored, and there is no real information on the true impacts of sometimes very costly FADs on local fisheries.

A good manual on their design use and cost efectivines has been produced by SPC here

The Pew Environment Group evaluated that FAD deployments have more than doubled since 2006 in the eastern Pacific Ocean alone. Without being as scientific my personal evaluation trouhj my wrk documents, will say the same about the western pacific.

Still, there are few regulations for fishermen or vessel owners to follow, and no penalties for deliberately abandoning FADs at sea when they are no longer deemed useful or productive.

Some RFMOs have measures intended to improve the monitoring of drifting FADs, but the overall lack of standarised regulation makes counting these objects difficult.

Information on FAD deployments remains hard to find. Much of the data that would be needed to develop a precise estimate of their numbers exist but are confidential as industry invest heavily on the construction and electronics of it (just think how much 3 km of Polyethylene line will cost!) and they don't want other companies to use their FADS, so this information proprietary

In 2012 Pew took on the task of developing a ‘back of the envelope’ estimate of how many drifting FADs are currently in use, while acknowledging that it would be a challenging exercise and the results both imperfect and preliminary. Collating data gathered using three separate methodologies, they estimated that in 2011 the number of drifting FADs put into the oceans each year ranges from 47,000–105,000.

Using data on fishing obtained since then, along with new scientific research and an examination of recent trends in FAD use and technology, Pew has produced updated estimates indicating that the total number of drifting FADs deployed in 2013 ranged from 81,000 to 121,000. The upper estimate has increased by 14 percent since the calculations for 2011.

Other analyses have come to similar conclusions. For instance, the European Commission released a report in 2014 estimating that 91,000 drifting FADs are deployed annually. Meanwhile, new initiatives are underway to better track and understand FAD use. For example, three French purse seine companies, operating in the Atlantic and Indian oceans, provided researchers with detailed tracking data of FAD movements to create the most extensive analysis yet of how FADs move in those ocean areas.

Parties to the Nauru Agreement, a group of eight Pacific island states that have the world’s largest skipjack fishery within their waters, plans to implement an electronic tracking system that will allow monitoring of FAD numbers and locations in near real time to better understand the impact on the tropical tuna fishery. This will provide useful data to fisheries scientists and managers on the use of tens of thousands of drifting FADs in the western and central Pacific Ocean.

Starting in 2017, the Inter-American Tropical Tuna Commission (IATTC) will require vessels to provide additional FAD data and physically mark their FADs with unique identification codes.

Given the practical and feasible steps available to improve FAD management, they have been calls on RFMOs and fishing entities to:

Recently I quoted Dr. Shelton Harley presentation at the TunaForum in Fiji, where he reckon (and I totally agree) that sun powered/satellite data transmission capable Sonar devices attached to FADs are a massive game changer and complex development.

In the past the vessel had to go to their FADs and then see if there was fish around it; with this technology fleet managers from the desk somewhere in the world can direct the vessels to the FADs that are showing signal. Here is an example of what you can buy this days.

As anything in fisheries, there are no easy answers… in these aspects i always refer to something I learned many years ago: “the risk is never in the substance, is always in the dose”

The WCPFC’s Eleventh Technical and Compliance Committee (TCC11) met in Pohnpei, Federated States of Micronesia on 23-29 September to discuss technical and compliance matters in advance of WCPFC12 (and as always a mix bag)

TCC is responsible for administering the Commission’s Compliance Monitoring Scheme (CMM 2014-07). During the annual TCC meeting a review is conducted in a closed working group session of compliance of Commission members’ and cooperating non-members’ (CCMs) with obligations established in the WCPFC Convention, scientific data requirements, Commission Decisions and Conservation and Management Measures (CMMs).

TCC11 marked the fifth year of implementation of the Compliance Monitoring Scheme, with several days dedicated to conducting the compliance monitoring review. The compliance of 36 CCMs was reviewed with a priority list of over 100 obligations for 2014 (however the report is password protected :-( )

A three-tiered system of rating compliance was applied for the second year running, where members are rated for each obligation as compliant (green), non-compliant (orange) or priority non-compliant (red) (when a CCM is non-compliant for an obligation for two or more years, is breaching catch limits and/ or is not submitting Annual Reports). If a CCM is in compliance with all assessed obligations, TCC recommends an overall compliant rating to WCPFC.

Following the compliance monitoring review process, TCC11 developed a Provisional Compliance Monitoring Report to be forwarded to WCPFC12 for consideration which includes a provisional assessment of each CCM’s compliance status and recommendations for corrective action, as well as issues arising during the compliance monitoring review process and requests for assistance and capacity building.

While CMM 2014-07 includes provisions for responses to non-compliance, including the establishment of a small working group to identify a range of responses to non-compliance, this issue was not progressed by TCC11. Since the current Monitoring Scheme measure expires in 2015, time was also spent during TCC11 to develop proposed text to extend the Scheme into 2016 and beyond.

No one is dodgy... is all a misunderstanding

In previous years, a key TCC concern was continued failure of South Korea, Japan, Chinese Taipei and China to provide operational level data, which compromises the ability of the Commission to carry out its compliance functions, as well as reducing the robustness of stock assessments. At WCPFC11, operational level data requirements were included in the CMM on tropical tunas (CMM 2014-01) to help address this issue. TCC11 noted there has been significant progress in the provision of operational data from Korea and China, but further improvements are still required. Further progress is expected in 2016.

Discussions on the Regional Observer Program touched on the paramount concern for health and safety of observers, particularly in light of the recent case of a US-observer going missing from a Panamanian carrier in Peru, as well as other reported cases of harassment, intimidation and assault. WWF delivered a strong statement to TCC11 about the critical issue of observer health and safety and indicated that it will be pushing for market-based sanctions for companies/fishing vessels who violate observer health and safety. WWF’s position was supported by several WCPFC CCMs.

TCC11 discussed proposed amendments to existing WCPFC CMMs as well as new CMMs for consideration by WCPFC12.

On proposed new CMMs, at the time of TCC11 only one new proposal had been tabled by PNA for establishing a WCPO skipjack target reference point, which is a revision on their 2014 proposal to WCPFC11.

No new proposals tabled by any members on major changes to the existing measure or a proposal for a new measure for skipjack, yellowfin and bigeye, despite this being one of the most contentious and highly-debated measures in recent years.

However, TCC11 has recommended WCPFC12 address some ambiguities in the text (e.g. defining ’current’ levels) to better facilitate review of compliance with certain requirements.

Also, there are elements that are required to be addressed in 2015 by WCPFC12 including high seas purse seine effort limits, purse seine yellowfin catch limits and longline yellowfin measures.

Additional FAD measures for 2015 and the capacity management work plan may also be discussed. FFA members also met in late October for their annual Management Options Consultation where they usually prepare multiple proposals.

All this info was adapted from FFA's FTIN for the period Sept – Oct 2015 being Volume 8: Issue 5

As blogged before, I took a job that is a far distance from my usual topics... Bringing new tools to a traditional fishery. I like to branch out sometimes, and is good for my "interest" and it challenges me to "see" things with a new mindset.

Not the usual image of the Pacific

In Chile, benthic species, small pelagic and demersal fisheries, have historically been exploited by artisanal fishermen due to an initial open access to the fisheries and the opening of new global markets. Today, approx. 60,000 fishermen depend for their livelihoods and income on these declining resources. Despite the socioeconomic importance of the artisanal sector, its “development stage is precarious” due to organizational fragmentation and institutional weaknesses.

Understanding how small scale fisherman make ends needs with fishing is complicated, since the fresh fish trade involves transacting characteristics that are very difficult to be measured, without a specific ad hoc tool needed to understand the way fishing business works at small scale vessel level, furthermore the disparity of vessels characteristics at each location varies profoundly, hence making a generalist approach to the analysis of limited utility. Furthermore, the artisanal fishery organizational structures in Chile are highly complex and regionalised.

The understanding of the cost benefit reality for fisher operation, becomes even more relevant since the introduction of quotas, as the earnings of a fisher are based on a limited quantity of catch that has already a market value, hence knowing on trip by trip basis the earning and loss situation allows for catch planning. And if that wasn't enough, exclusivity fix price arrangements for catch do not reflect the cost of fishing due to the lack of a specific tool for that aim.

So mi first job was to adapt and update a spreadsheet we used in Samoa many years ago, to help the fisherman association to keep a much better tab on if they make money or the don't.

The spreadshhet is design to give a immediate appreciation of where they are in terms of cost benefit.

My next proposal is way more ambitious... from the findings it was clear that a tool that improves the transparency of the value chain, while providing traceability and information to fisher, buyers and authorities alike, could alleviate many of the shortcomings of the present scenario for many fisherman.

In fisheries today, new ICTs are being used across the sector, from resource assessment, capture or culture to processing and commercialization. Some are specialist applications such as sonar for locating fish. Others are general purpose applications such as Global Positioning Systems (GPS) used for navigation and location finding, mobile phones for trading, information exchange and emergencies, radio programming with fishing communities and Web-based information and networking resources.

However many of these especially dedicated tools are in a cost range that exceed the financial capabilities of the fishers, or have to be install and removed form the vessels. However, the new generation mobile phones are incredible tools that bring together in one various different “technologies”, they are at once a personal locator beacon, a GPS navigation device, and GPS equipped camera, besides being a 2-way communication device.

Based on work prior done in East Timor and Indonesia plus a existing tool being used in the Caribbean, I proposed the development of a app containing a “suite” of tools that could be used from a mobile phone that could ally itself the following focal FAO focal points:

So I proposed the conceptual design of a Android App (initially named “PescApp”). This app will open a “suite of services” that are at the disposition of the registered fishers including regulatory and traceability components as well as a market and trade services.

The App concept is not new, the original was one in Trinidad and Tobago and it looks like the one illustrated here. I just expanded the concept to:

Registration

SOS

Navigation / Weather Information

Compliance

Alerts

Traceability

Market Information and Auction

However is important to point that while all fisherman interviewed had a “intelligent” phone of some sort, and all of them reported having 3G signal up to 10 miles from shore (hence the technology and tools are well incorporated by the ultimate beneficiaries). The App are not expected to yield desired outcomes unless these are well articulated and drive the App design and implementation strategy.

A recent report in ITC in small scale fisheries topic, nails the complexity of this process:

Rejuvenation of the small-scale fisheries sector with its complex interdependencies and rich ecosystem is not an easy, mechanical or even technical challenge. The integration of ICTs in the small-scale fisheries sector requires the development of various cognitive and skills-based capacities, as well as the formation, refinement and authentic ownership of new attitudes and behaviours. It calls for the human systems to be established to, in turn, articulate the various processes that in concert, aggregate to achieve bold, meaningful and consensual outcomes.

Technology cannot take the place of collaboration, engagement and negotiation, and can do little to take the place of time. Technology cannot provide a solution to the fundamental challenges, which limit participatory governance in fisheries anywhere in the world. It can only be as good as its human partners who must plan, design, implement and nurture the sector, its agents and its growth.

I wrote about this in the past, but my friend and college Christopher Kevin from PNG's NFA that did the programming published recently a more detailed explanation on the system. So I share it here.

The objective of the Fishing Accountancy System (FAS) is to prevent the mixing of or processing and Exporting/Selling of Fish that has been caught and landed legally from fish that has been Illegally caught and landed, as a necessary tool for PNG's system for EU Catch Certification

The FAS is controlled and maintained by the NFA's Catch Documentation Schemes (CDS) team, and it works this way:

When a Catcher or Carrier calls into PNG port to land, a Landing Authorization Code (LAC) or Unloading Authorization Code (UAC) is issued to the catcher/carrier.

SCENARIO 1 - Wewak Port Example for a Catcher Landing Fish at ABC Seafoods Corporation:

SCENARIO 2 - Lae Port Example for a Carrier Landing Fish from 3 different Catchers at XYZ (PNG) Limited:

Work through - Fish Transaction and Balancing:

Every time an export is made, all the details are entered into the system by the CDS Officers/CDS Monitors/Export Officers.

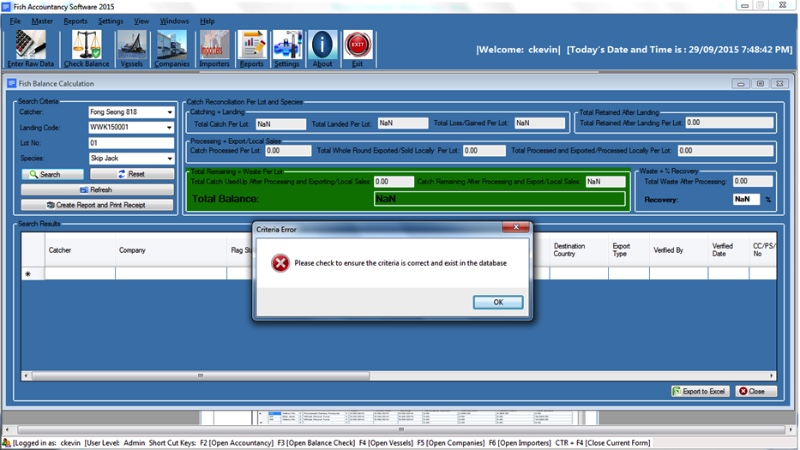

For every new Export, the Catcher Name, LAC, Lot # and Species are entered into the system to check the Fish Balance remaining per specie and Lot # for this particular catcher. See fig 1 below:

Fig. 1- Fish Balancing/Transaction Screen

Using Scenario 1 – Fish Usage

From the above fish usage:

If the Catcher with said LAC, Lot # and Specie is NOT ALREADY registered in the system, No Fish Balancing Records/Details will be displayed on the screen and an Error Alert Message Box will be displayed notifying the user that there are no records available for this search criteria. The user will now enter the new details into the system and export approval is given. See Figure 2 below:

Fig. 2 Fish transaction details Per Lot# and Species.

For the above example, the system will now display on the screen as seen below

Fig. 3: Fish transaction details Per Lot No and Species – Error message indicating that there is no record available as per the search criteria

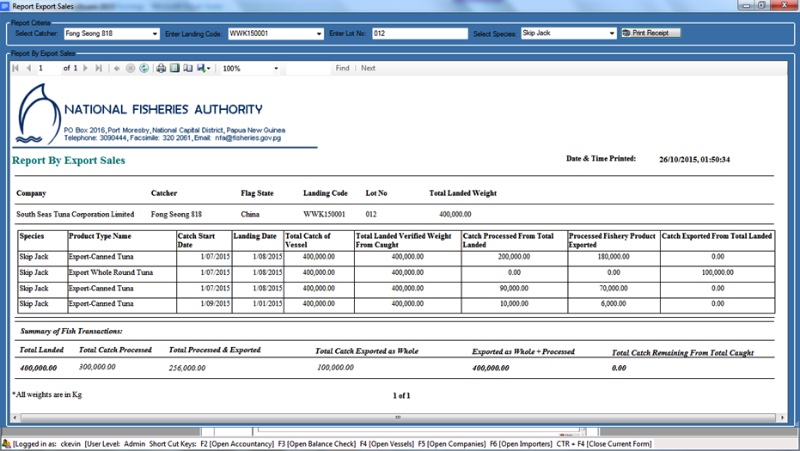

Fig. 4: Report to display the fish transaction details Per Lot # and Species

Fig. 5: Report to display the Total Quantity Processed (Loins and Canned) or sold Whole Round Tuna Per Lot# and Species

Fig. 6: Report to display the Total Quantity Sold Locally or Sold Locally as Whole Round Tuna Per Lot No and Species

Obviously the reporting can be customised to reflect any (or many) of the parameters in the relational database, and the design of the system is flexible as to be adapted to other fishery operations.

While is quite frustrating to explain screens on a text, all is possible with good will and patience, and from what I know NFA and Christopher (who is a great guy) are happy to share their systems and knowledge.

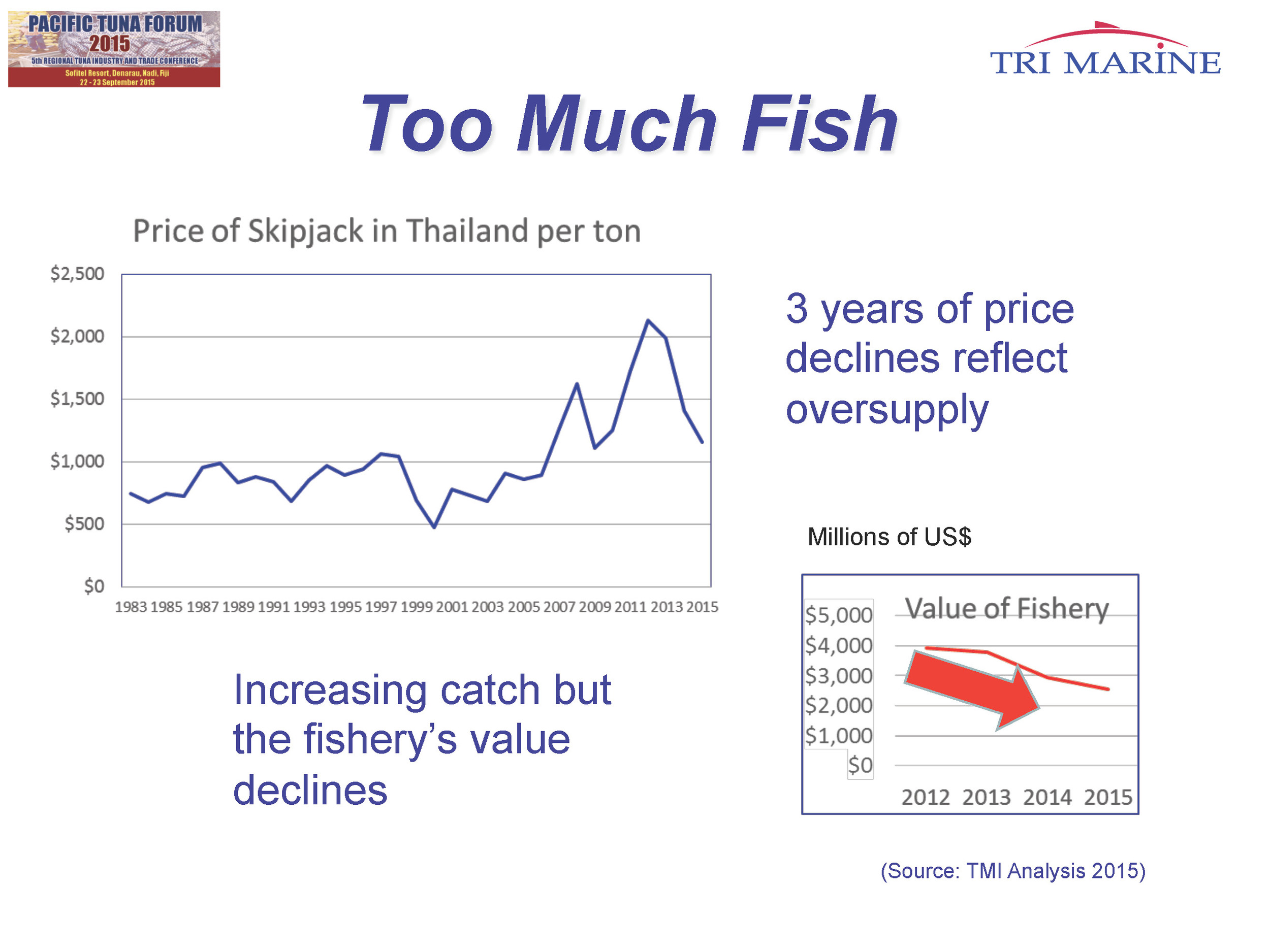

That is definitively not the type of statement that you read often in fisheries... but that depends from where you look at it. I have known Phil Roberts (from Trimarine) for a long time, he knows the tuna world from the inside out, and I always like to listen to what he has to say.

He always has the right information to complement his words. The graph above is explanatory on itself the world is catching to much fish and that oversupply is driving the price down, so what is the point?

No one wins... that is what my 13 years old boy said when I explained the graph... Is so evident that I just don't understand how we got here.

From 2000 – 2014 catch increased by 75% in the WCPFC. That leads that to oversupply and depressed market prices, there has been a 39% drop in value from 2013 to 2015.

Oversupply is bad for boat owners. Oversupply = low prices = unprofitable boats.

Low prices are bad for island based processors are only low prices are good for brands and dutiable processors.

SPC indicates that 220 seiners could fish to 50% target reference point. The WCP fleet may need a 25 to 50% reduction and make more room for locally flagged vessels.

Every year at this time is Technical and Compliance Committee (TCC) meeting in the western and central Pacific Ocean in Pohnpei, Federated States of Micronesia. And a lot of fisheries technical informations is prepared and presented. Is one of those places where the scientists present their data and the politics ignore it...

As the guys from ISSF said: While some members have made great progress through stakeholder collaboration throughout the intersessional period, given the ongoing and pending issues again on the agenda, one wonders if we are attending TCC 10 or TCC 11? There is certainly a sense of déjà vu as we prepare for this meeting.

Reading fisheries papers is not for the non initiated... and the dynamics and problems of Big Eye tuna are not one dimensional. However, in my eyes the graph below from this paper just tells all the story:

Each colour is a different part of the pacific where the data comes from, the trend is clear even if you are not a fisheries biologist.

Management failure at its best

Every year around September - October I do a few weeks of work in Latin America. Working here is a bit of sabbatical: completely different language, fisheries, realities, problems, etc… It put my head back to the other reality of fisheries; where catching fish is part of everyday subsistence and not only a job that brings money.

Small scale long line fisherman in Chiloe Island.

Over the next week I will be working again for the Swiss Government SIPPO Programme in Peru, selecting small fishing operations for their direct contact with world buyers cutting off the middleman.

Then I’m off to Southern Chile, working for WWF Smart Fishing Initiative, supporting the development of low cost technologies that facilitate catch volumes evaluation, traceability, transport logistics and fisherman safety in the small scale hake fishery around Puerto Montt.

I always believed that Information and Communications Technology (ICT) can greatly benefit both fisheries administrations and fishing communities alike, I have utilized information and communications equipment in a wide range of initiatives. And more and more I believe that new generation mobile phones are incredible tools that bring together in one various different “technologies”. They are at once a Personal locator beacon, a GPS navigation device, and GPS equipped camera… besides being a Communication device! And in fisheries we have use for all of them!

Those “tools” can be easily and cheaply interfaces with google maps platforms and we then appeal to willingness of the social responsibility and sustainability sections of mobile companies to support it, so many positive advances in small scale fisheries can be acheived via win-win scenarios… the only things you need are a phone, a waterproof cover, some call credit and thinking out of the box… (I like that last bit a lot!)

Hence, I see this a good challenge and a opportunity to refresh my head and then go back to tuna, IUU and Catch documentation at the end of November.

I keep updates coming.

A couple of weeks ago, when I was in the Pacific Tuna Forum in Fiji, I posted about the presentations I was keen to hear and see. Today I present Shelton Harley's one, he is the Principal Fisheries Scientist (Stock Assessment and Modelling) of SPC's Oceanic Fisheries Programme. Shelton is a very clever man at the top of its game, and equally important, a good communicator of the science and status of the stocks.

I will attempt to pass some of his message, that was quite strong and cautionary, most of the images and graphs are self explanatory.

2014 was the largest in tuna fishery catches in history 1.96 Million Tonnes of skipjack. To make sense of this number, see above: If we were to put all the skipjack caught nose to tail, the line would extend almost half a million km... enough to go around 100000 km beyond the dark side of the moon.... that image blew my little brain off into pieces.

Every year more and more Skipjack get added to the statistics while the rest has been quite stable... but for how much more?

The Pacific catches are way more than all other oceans combined... just some Kiribati and PNG and you have more than the whole Indian ocean. This numbers are staggering.

The usual graphs that are shown, have green (is all good), orange (we need to take measures) and red (overfishing)... this time he believes that that green gives a fake sense of security... hence he circumscribed the statatus of the healtiest stocks to a smaller oval of where the fishery operates at good biological and economical returns. under that view, even skipjack looks borderline.

Hence, the overall picture is not very good for the other pelagics

Purse Seine fishing is increasing it efficiency , and there is an increase in the number of sets. Skipjack biomass is going down and catch rates are going up.

Sonar FADs (Fish Aggregation Devices) are the biggest game changer, in the past the vessel had to go to their FADs and then see if there was fish around it; with this technology fleet managers from the desk somewhere can direct the vessels to the FADs that are showing signal. Also helicopters are back in the fleet as there is lot of replacement vessels. New purse seiners are more powerful and more efficient. (And many are subsidised as i suggested before)

Of course this impact Yellowfin, as is to be seen in the 3 maps or relative abundance above. Juvenile Yellowfin associates to Skipjack and is caught with it, as purseine is not really a discriminatory fishing method.

Hence the take home message is sobering, we have long reached or exceeded long term sustainable catch levels. The harvesting at such level is also felt in nations that do not catch Skipjack, as there are ecosystems implications that are not well studied yet.

The solutions to these issues are not new:

Unfortunately, the precautionary words that he has, seems to fall in the deaf hears of most DWFN and some Pacific Islands decision makers. But good on him for bringing these issues up in public forums.

I always maintained that the region is very lucky to have organisations like SPC, that can attract and maintain scientists of Shelton's caliber. Their analytical capacity and the level of the mathematical modelling that guys like him do is quite amazing. Total respect to him.

Is the 20th anniversary of the FAO Code of Conduct for Responsible Fisheries, a unique document that is not always valued as it should. FAO media unit interviewed some worldwide key stakeholders on their views about the importance of the Code of Conduct and what they see as the main challenges to overcome to fully attain the objectives of the Code of Conduct over the next 20 years.

By some reason they also asked me... This is how I sound in my mother language.

During the FAO Expert Consultation I was invited in Rome in July, FAO asked my view on the FAO Code of Conduct for Responsible Fisheries and the challenges it faces.

Basically I say that for me, the code is reference point that we all should mantain as yardstick in whatever area of fisheries we work. We need to have a "masterplan set of guidelines" and that is what the code ought to be.

I also say that the key challenge that has faced and continues facing is exactly that! We need to keep inthe forefront of whatever we as the "meta language" we use, and is not always done.

What the code "is" and "do" is explained in the video below by my ex colleagues and friends from FAO.

What is the Code of Conduct for Responsible Fisheries? Is a introductory document to the code has been translated to most languages of the world, and I'm happy to see that includes many of the Pacific Islands ones, click on the links for versions in Cook Islands Maori, Fijian, Taetae ni Kiribati, PNG Tok Pisin, Solomons Pijin, Samoan, Tongan, Tuvaluan, and Vanutu Bislama.

Recently came across this very good article about fisheries subsidies (a topic that normally hits me in the guts) by some heavy weights in terms of international trade Pascal Lamy (ex DG of WTO), Oby Ezekwesili (cofounder of Transparency International) and José María Figueres (ex President of Costa Rica).

Based on 2006 figures

This also ties up with the figure above, that notes that the global cost of fisheries subsidies is greater than the cost of IUU fishing.

The article presents good figures and arguments, hence is worth reading:

The just-adopted Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) are expected to herald the start of a new era in global development, one that promises to transform the world in the name of people, the planet, prosperity, peace, and partnership. But there is an ocean of difference between promising and doing. And, while global declarations are important – they prioritize financing and channel political will – many of today’s pledges have been made before.

In fact, whether the SDGs succeed will depend to a significant degree on how they influence other international negotiations, particularly the most complex and contentious ones. And an early test concerns a goal for which the Global Ocean Commission actively campaigned: to “conserve and sustainably use the oceans, seas, and marine resources for sustainable development.”

When political leaders meet at the tenth WTO Ministerial Conference in Nairobi in December, they will have an opportunity to move toward meeting one of that goal’s most important targets: prohibition of subsidies that contribute to overfishing and illegal, unreported, and unregulated fishing by no later than 2020.

This is not a new ambition; it has been on the WTO’s agenda for many years, and it has been included in other international sustainable development declarations. But, even today, countries spend $30 billion a year on fisheries subsidies, 60% of which directly encourages unsustainable, destructive, or even illegal practices. The resulting market distortion is a major factor behind the chronic mismanagement of the world’s fisheries, which the World Bank calculates to have cost the global economy $83 billion in 2012.

In addition to concerns about finances and sustainability, the issue raises urgent questions about equity and justice. Rich economies (in particular Japan, the United States, France, and Spain), along with China and South Korea, account for 70% of global fisheries subsidies. These transfers leave thousands of fishing-dependent communities struggling to compete with subsidized rivals and threaten the food security of millions of people as industrial fleets from distant lands deplete their oceanic stocks.

Global Ocean Commission data (not sure about the accuracy of the data, in no way I believe that China and PNG are in the same bracket)

On the high seas, the distortion is even larger. According to fisheries economists, subsidies by some of the world’s richest countries are the only reason large-scale industrial fishing in areas beyond coastal countries’ 200-mile exclusive economic zones is profitable. But fish do not respect international boundaries, and it is estimated that 42% of the commercial fish being caught travel between countries’ exclusive zones and the high seas. As a result, industrial fishing far from shore undermines developing countries’ coastal, mostly artisanal, fisheries.

Eliminating harmful fisheries subsidies by 2020 is not only crucial for conserving the ocean; it will also affect our ability to meet other goals, such as our promises to end hunger and achieve food security and to reduce inequality within and among countries.

The credibility of both the WTO and the newly adopted SDGs will be on the line in Nairobi. The Global Ocean Commission has put forward a clear three-step program to eliminate harmful fishing subsidies. All that is needed is for governments finally to agree to put an end to the injustice and waste that they cause.

Fortunately, there are encouraging signs. Nearly 60% of the WTO’s membership supports controlling fisheries subsidies, with support from the African, Caribbean, and Pacific Group of developing countries – together with the EU’s contribution to improve transparency and reporting – giving new momentum to the effort.

Among the initiatives being put forward in advance of the Nairobi meeting is the so-called “NZ +5 proposal.” Co-sponsored by New Zealand, Argentina, Iceland, Norway, Peru, and Uruguay, the plan would eliminate fisheries subsidies that affect overfished stocks and contribute to illegal, unreported, and unregulated fishing.

The Global Ocean Commission urges the remaining 40% of the WTO’s members – and especially the biggest players currently blocking this process – to accept the relatively modest proposals on the table. A sustainable future for our planet and its oceans depend on it.

The original is here

I have never meet Mercedes Rosello, other than by tweeter (sign of the times) but she knows her stuff very well!, and has been very kind to my work/blog in more than one occasion. As far as I know she she is a PhD researcher and runs House of the Ocean (a not-for-profit consultancy) and a blog (the IUU fishing blog). Her more recent piece is very informative in terms of the legal perspectives of the "concept of IUU fishing". She kindly allowed to "re blog" (is that a real word?) her content. I recommend you read her piece, as I just pick up some quotes from her blog.

some of 100 scenarios....

The first global instrument to introduce the expression IUU fishing was the 2001 International Plan of Action to Prevent, Deter and Eliminate Illegal, Unreported and Unregulated Fishing (IPOA), a non-binding international tool.

Known as a toolbox for States to guide them in the fight against undesirable fishing practices, the IPOA is extensively referenced as the source of the definition of IUU fishing, contained in its paragraph 3. This definition has now been integrated in treaty law, the legal regimes of several States, and European Union legislation. Yet, despite its popularity, the term is controversial due to its lack of legal clarity.

Rather than understanding the term IUU fishing as a single tool with which to assess conduct, it is useful to think of it as three distinct but overlapping categories. Each category presents a different perspective on undesirable fishing activities. Except for the first one, which is all-encompassing in its descriptive simplicity, the categories are not comprehensive. Further, they do not comprise a set of standards on which to judge the illegality of a fishing operation, or the conduct of a State in respect of its international obligations. In this respect, the 1995 Fish Stocks Agreement is better equipped to deal with such tasks.

First and second categories: illegal and unreported fishing

The first category, that of illegal fishing, is set out in paragraph 3.1 of the IPOA. It is a straightforward description of what makes a fishery conduct a wrong in law at the domestic and international levels.

Firstly, domestically: when the conduct of a vessel (a more accurate reference would be to the person or persons responsible for its operation) contravenes applicable domestic law, it is illegal. Secondly, internationally: certain conducts by vessels may demonstrate a shortfall by the State responsible for their control in the observance of its international legal obligations. When this occurs, there may be an international wrong.

Ultimately, however, whether any illegality has indeed occurred will need to be determined by a relevant authority. Domestically, this may be an administrative authority or a court of law. Internationally, a tribunal with jurisdiction.

A second category, that of unreported fishing, is set out in paragraph 3.2 of the IPOA. Domestically, it refers to vessel conducts that contravene the specific laws that regulate the reporting of fishing activity or catch. Internationally, paragraph 3.2 goes on to refer to activities that contravene the rules of regional fishery management organisations (RFMOs) in areas of the high seas where they have regulatory competence. The reference to a contravention implies that the subject (a State) must have agreed to abide by those rules. If such State permits a vessel in its register to operate in a manner that is inconsistent with those rules, the State may be committing an international wrong. Hence, domestically as well as internationally, unreported fishing is a sub-category of illegal fishing. Curiously, other than RFMO rules no reference is made in the IPOA to the contravention of international laws that oblige States to report on fishery data. Given this incompleteness, unreported fishing has little value as a legal category beyond national and regional management contexts.

These categories describe what illegality looks like, but they do not act as legal yardsticks. Domestically, the illegality of a fishing activity can only be determined by way of assessment of the conduct of an operator against the applicable municipal laws by a competent authority. These laws may vary from country to country. However, before the birth of the IPOA, the 1995 Fish Stocks Agreement (FSA) had already typified a number of fisheries activities that it referred to as serious violations. State parties to the FSA are required to address those violations in their respective domestic legal regimes. The non-exhaustive list in FSA Article 21.11 includes conducts such as fishing without authorisation, failing to report catch, using destructive fishing gear, or obstructing an investigation by concealing evidence, to name a few. Hence, in FSA State parties at least, those will be the conducts that will be restricted or outlawed – they will be the illegal fishing conducts to which the IPOA refers or, at least, some of them.

However, the regulatory influence of the FSA does not extend to non-parties, or to the conservation and management of stock that is neither straddling nor highly migratory. Where non-transboundary stock is located in the EEZ of a coastal State, it is left to the discretion of that State to determine what fishing activities should be restricted or outlawed. It will need to do this within the general parameters of international law, the 1982 UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) and other treaties to which it is bound, including bilateral agreements.

Whether illegal fishing conducts may also be typified as criminal will depend on the discretion of each State. The FSA does not oblige State parties to criminalise any fishery behaviours, only to address certain conducts as serious violations. Most countries choose to do this by way of non-criminal public law and administrative measures. Currently, illegal fishing is not considered a transnational crime in accordance with the UN Convention on Transnational Organized Crime, and therefore States are not obliged to treat it as such. Further, the IPOA discourages this, considering the rigours of criminal law in terms of proof and process too onerous.

It is, however, noteworthy that some States have chosen to criminalise some specific conducts associated to illegal fishing practices. In other cases, strategy documents have referred to illegal fishing as a crime, but the relevant legislators have failed to adopt the necessary laws to ensure criminalisation in their domestic regimes.

Finally, a domestic instance of illegal fishing – whether criminal or not – will be of little significance internationally unless an international legal standard of conduct has also been contravened by a State with responsibility. At the time of writing, such legal standards are principally found in general international law, UNCLOS, the 1995 Compliance Agreement and, in respect of straddling and highly migratory stock, the FSA. Whilst several paragraphs of the IPOA have substantially defined some of those rules, its voluntary nature makes it unsuitable as a yardstick against which the conduct of a State can be assessed in order to determine its possible illegality.

Not just inspecting...

Third category: unregulated fishing

The third category, unregulated fishing, is set out in paragraph 3.3 of the IPOA. It has two distinct prongs:

The first one refers to activities carried out inside areas and for stocks under the regulatory competence of RFMOs, in a manner that is inconsistent with their conservation rules. Such activities must be carried out by vessels without nationality, or by vessels flying the flag of a State that has not agreed to be bound by the rules that RFMO (for States who have agreed to this, the activity contravening the rules would be categorised as illegal fishing, as explained above). In effect, this label is slightly misleading, because the sea areas and stocks to which it refers are regulated by RFMOs, notwithstanding the States or vessels’ choice to disregard such regulation.

The second prong refers to activities carried out in a manner inconsistent with the flag State’s international obligations in respect of high seas areas or stocks not affected by RFMO conservation or management rules. Hence, the label unregulated fishing here refers to the absence of RFMO rules.

Although superficial reading of paragraph 3 of the IPOA may suggest that unregulated fishing is an entirely separate category from illegal fishing and is therefore legal, this is not the case. As paragraph 3.4 of the IPOA subsequently clarifies, unregulated fishing will also be illegal if it is inconsistent with the flag State’s international obligations. Beyond obligations acquired in the institutional context of RFMOs, States also have conservation and cooperation obligations derived from general international law and applicable treaty law.

However, the protection offered to those ocean areas and stocks by international law is generally considered thin and unclear in practical terms, making assessments of legality particularly difficult. This is specially so in cases where States have not agreed to important treaties such as the 1982 UN Convention on the Law of the Sea or the 1993 Compliance Agreement, or where no other binding rules (such as those that may be established in a bilateral agreement) exist.

Hence, unregulated fishing is a wide spectrum category comprising high seas activities that are always pernicious insofar as they undermine conservation and cooperation efforts, but whose illegality may be uncertain in accordance with the current international framework. The value of this category lies not in its ability to facilitate an assessment of what may constitute legal or illegal conduct, but in its usefulness to ascribe a negative value to certain fishing activities irrespective of their illegality. This can be practical for a State or group of States who have adopted certain conservation rules, and have to deal with other States who have not done so.

The conserving States may be reluctant to commence international proceedings against the non-conserving States for many reasons, ranging from the political undesirability of engagement in a high profile dispute, to cost, to lack of confidence in the international legal framework, to name a few. In this context, such States may opt for the deployment of trade measures against non-conserving States. Amongst the advantages of this process are the presence of incentives, as well as the avoidance of the rigours associated to international legal process.

Subject to a number of procedural conditions, if the products from the non-conserving States have been captured in a manner that is detrimental to conservation and are excluded by the conserving States on the basis of a non-discriminatory process, they may be considered compliant with the rules of the World Trade Organisation and be, therefore, viewed as legitimate.

Conclusion

The ‘hold all’ composite term IUU Fishing is instrumental in ascribing a negative value to a wide range of fishing and fishery support activities whose illegality is uncertain in order to enhance the accountability of operators and States through trade measures. Beyond this, paragraph 3 of the IPOA does not constitute a proper standard against which the conduct of an operator or a State can be legally assessed by a relevant administrative or judicial authority. Its voluntary nature makes it unsuitable for this task in any event. Appropriately therefore, the IPOA does not list actual behaviours by private actors that States can then domestically class as illegal.

By contrast, the FSA does contain such list in respect of fishery activities targeting straddling and highly migratory species. The list in its Article 21.11 should be replicated, expanded and changed where necessary to be made applicable to non-transboundary stocks across domestic regimes, and in the context of bilateral fishery agreements. This, plus the treaty’s integral management of RFMO conservation consent by State parties makes its adoption and implementation essential in the management of illegal fishing and the delimitation of unregulated fishing to cases where there is no RFMO regulation.

The FSA is, therefore, an essential tool in the regulation of fisheries and the eradication of illegal practices, and States should work hard to foster its generalised adoption alongside the adoption of national plans of action and the Port State Measures Agreement.

In a move that was expected (and truly deserved) the EU lifted the "yellow card" it had on Papua New Guinea since June 2014.

IUU fishing is actually mostly about people, cultures and greed... fish is just what they do. (the body languages in this scene tells a lot)

The EU's press release that announced it recognises that PNG has "amended their legal frameworks to combat IUU fishing, strengthened their sanctioning systems, improved monitoring and control of the fleets".

The good news touches me at personal level, if you follow this blog you must have noted that I have written about working there (here, here, here and here). Over the last 18 months I have worked many times in the country supporting their strengthening actions, and I have been a front row witness of the personal and systemic transformation of the National Fisheries Authority (NFA) staff in charge of the Catch Certification Scheme and its associated Fish Legality and Accountancy controls. I know is very rewarding to them (and me) to feel that they have helped pushing their country off a sticky situation (they are VERY proud people).

Professionally for me is a great satisfaction, there is no template on "how" the system should work... The EU in this area wants outcomes and does not rule how you get there. So is up to countries to come up with systems that provide those results.. the few model available are all in developed countries with vastly different realities than PNG. In PNG we say that if something works here, then there is no excuses not to work anywhere else... (listen to that Philippines, Korea, China and Taiwan!)

So I'm very thankful to NFA, their management and staff, as well to my contractors FFA/DevFish II, for having trusted my vision and the unorthodox development of my systems. We delivered the results expected by the EU, but from a more efficient exporting country perspective and not from a market imposition.

Over the years I made "tru" friends in PNG, which is in many ways a 2nd home for me in the Pacific. I'm immensely proud of the people have I worked with, because it has been 100% their own merit, drive and pride that got the yellow card lifted. Good'n'ya wantoks!

Furthermore, I'm happy to see the EU tackling the bigger guys too! I knew that Taiwan was in the pipeline since April, but is good to see it happening!

I have yet to see (in over 15 years doing this work in the pacific) a Taiwanese flagged or owned (even if flagged in Vanuatu) longliner that is in full compliance and that reports their logsheets in time (perhaps they are... I have just not seen them). So hopefully they do some deep work like the one done in PNG!

Taiwanese longlining logsheets... works of art...

The declining status of the Southern Albacore Fishery has been well documented. Even in its more limited stance; the fishery in Fijian waters that is under a MSC certification, may not be able to pass the next certification (as well there are no way to pay for it, without the catches)

Chinese Longliners in Suva Harbour (Beautiful image for a sad reality)

While the reasons are various, the main culprits are overcapacity, subsidies and the failure of the regimentation and controls in the high seas (a responsibility of the WCPFC)

Is quite sad, as it used to be a profitable fishery that employed mostly Fijians. Unfortunately the concessions and subsidies provided to the Chinese fleet throw the situation into the doldrums.

See below a press release by FTBOA (Fiji Tuna Boats Owners Association) quite self-explanatory

It was a professional and personal challenge to give a talk in regards the “Impact of the EU Yellow cards in the Pacific” at the Pacific Tuna Forum in Fiji this week.

The EU made a game changer with its IUU regulation by denying market access to those products that did not arrived to the border with a “official guarantee” of the flag state of the catching vessel/s attesting on the legality of the catch. Conceptually that is just awesome.

I always recognised and supported that principle, my “beef” with it has been with the practicalities of the Catch Certification Scheme (the tool the regulation uses), the design of the certificate, the fact that is paper based and the backwards (from market to vessel) approach taken less than year after it was 1st introduced (when initially was forwards vessel to market). The fishing industry dynamics and its operational complexities where in existence before the 2010 implementation of the IUU regulation, hence operationally the legislation would have benefited from a much deeper study and understanding of the reality, prior to trying to capture it under a substandard scheme.

My work has been always aimed to make it better from a operational perspective but not to abolish the concept… In fact I’ve dedicated most of the last 5 years of my professional life to help countries to comply with it, by working around many of the operationally frustrating challenges of the scheme while at the same time strengthening the "in country" tools required so the legislation key objective (minimise IUU fishing) is not lost.

Slide 1

Other small countries in the world got yellow cards and some of them reds, like Belize, Togo, Sri Lanka, etc. Notably major countries with weak compliance records got yellow cards as well, like Philippines and Korea, but these were removed a short term later (no that one notice much change in the quality and content of their catch certs). The latest country under this process is Thailand, but interestingly even if they get red carded, the impact in the tuna world would be minimal… because the “ban” in exports to the EU will only affect tuna caught by Thai flagged vessels… and paradoxically there are none. The biggest exporter of can tuna in the does not operate a tuna fleet (welcome to one of the many twists of the fishing world).

In any case, I decided immediately that there was no point of dwelling in the perceived politics of the situation, but more constructively on the advances that this “yellow cards” have catalysed in the Pacific regions in terms of MCS and related control systems, and particularly the in regards the strengthening of the EU Catch Certification Scheme. And I’m happy to say, we got plenty of positives to report.

Slide 2

The 1st step we took was to foster the understanding of what this whole issue was about, because in reality not many people in the region (and the world I may add) really understood what it was about. The training provided by the EU prior of its implementation was minimal and quite poorly structured (one session for the whole pacific in New Caledonia, based on a powerpoint that just copy and pasted the regulation – I still have it! – as a trainer I can assure that is the best way to loose an audience). Followed by the late publication of a “handbook” which provides guidelines and answers on the implementation of the EU IUU Regulation is a lengthy and wordy document and it was written before the implementation of EU IUU Regulation itself, so many scenarios are not contemplated and the substantial changes of interpretation (such as the Weight in the Catch Certificate - WICC notes 1&2), make the document, while well intended, of very limited use.

Slide 3

For me the analogy of the iceberg fits the situation, what we only see is the tip: the certificate (the-unfortunately- piece of paper). But what really matters is what is below… what I called the “fish legality” and the “fish accountancy”, so all this needed to be strengthen and systematized, so the tip is meaningful.

Hence was very important to develop and standardize a training program that dealt with the conceptual issues first and later with the scenarios that the regulation requires to be contemplated, and FFA's DevFish II programme contracted me for that.

Slide 4

The Certificate itself is a complex document with a multi-layered structure of responsibilities that do not always correlate chronologically with reality, hence detailed explanations and a standardization of the way the information is to be presented was required. These also had to be expanded indirectly to foreign flag states that operate in the region as to maintain “a system” that is homogenous trough the operational chain. The “quality” of foreign certificates was a constant source of frustration for many of the officers we worked – how come they send us this shitty documents and they are not yellow carded? Was a frequent question, that I had no answers to provide.

Slide 4

The next element was to train on the content and scenarios presented by the regulations and understand which ones applied to each case in each island country. This was not easy, because besides the difference in the industries in each country it had to consider as well the interactions in between the Catch Certification, the Health Certification (normally under Health Authorities) and Certification of Origin (under Customs)… so not easy task.

Furthermore we had to consider the scenario of the transhipment countries, as this countries are part of the system but not initially contemplated (not “notified” using the EU IUU lingo) but have an important role without getting any direct benefits (other than fees for use of their ports), as this countries are not allowed to trade fish with the EU because they lack of sanitary authorisation. As in the other cases, all this knowledge had to be built from scratch.

Slide 5

Initially we had to understand how to re-structure the traditional view of MCS into a more holistic approach. Fish does not become illegal during processing, is caught illegally. Therefore if we stop it before landing, then a big chunk of the problem is gone… but then we also need to stop the laundering of illegal fish with legal fish. So we introduce the concept of the "Unloading Authorization Code" (UAC) and Fish Accountancy to link with MCS.

The concepts “mixes” two basic elements; the requirements (in one way or another) of Port State Measures Agreement (PSMA) and a Key Data Element needed to follow a landing through the value chain. Under PSMA, vessels have to seek advance approval to enter a port, sufficient to allow adequate time for the port state to examine the information provided. Hence the information required needs to be provided and assessed to facilitate a decision as to whether or not to deny or grant entry. If an “authorization” is given, either the master or the vessel’s representative can present the authorization to the authorities when the vessel arrives in port.

This “authorization” will need to be “coded” (on some form or another) as to be recorded in one way or another as to be able to review and accounted and potentially crosschecked if it is deemed necessary. So why not simply use this Unloading Authorization Code (UAC) as the tool for the initial Key Data Element required for any Catch Documentation Scheme or traceability analysis along the value chain from landing to consumer (or wherever it is needed or most cost effective).

Furthermore, most fishing vessels operators (company own or independent) do maintain a trip or voyage coding systems in order to monitor logistics, fuel consumption, crewing rosters, general costs and more importantly “final payments”(which are in the form of a % of the catch volumes, species composition and values) are to the traced back to that landing, minus the fix costs. Therefore the concept already exists in the sector, so this UAC becomes a better and standardised use of an existing tool.

The "Process" associated to the use design and use of the UAC is as follow:

Arrival notification