I had a job lined up as a deckhand in a small coastal trawler of Mar del Plata because while I knew how to take a boat and operate it from A to B, I didn't know shit about fishing. Thankfully, a skipper (a good man named Braulio who lost his son in the war just the year before) took me under his wing and allowed me to learn from him and many others after him.

It was a steep learning curve that, after 40 years, hadn’t stopped yet, mainly when, after a few years of fishing, I got into university and got involved in fisheries science and management to then, go back to fishing in the Pacific in the early 90’s to re-start the road that took me to being here today.

Yes, many things have changed since then, some for good… some for bad (and some that feel the same).

I like to be a positive person, so start with the good things:

Stock assessment and data… this is where I see the most significant change… the stock assessment models of today and the data [path feeding them is sooooo much better than it ever was… I remember coding in Cobol on pathetic (for today’s standards) loops to run Virtual Population Analysis on computers that had less than 0.1 % of the computational capacity of my running phone today. Remember doing plots by hand and working with models that were just minor upgrades from the Beverton–Holt model. My colleagues in SPC, for example, run some more of the most sophisticated models in the world that have moved aeons from then; hence the accuracy of the assessments is astronomically better than then. Add to that the almost live capacity of electronic monitoring to feed those models in real-time…, and we could be talking about a different universe (even if some of the assumptions of those models stayed the same)

Monitoring, Controls and Surveillance… technology allows us to know so much more than ever before about fleet dynamics and fishing efforts… when I started, we just left. We had a radio, and that was it. No one knew where we were, what we were doing, if we sold fish or unloaded fish on the side before coming to port, if the catch declaration on paper (if necessary) matched entries at factories. Sonar and Satellite technology combined, in particular, made such massive changes.

The other side of the coin about advanced Sonar and Satellite technology is effort creep; finding fish was never so easy as today. We then relied on experience and advice from other friendly or family-related skippers. I remember being a “weirdo” by bringing knowledge about “water mass”, fronts and thermoclines…. The crew were looking at me like mad when I was dropping thermometers or longlines with a potato every 10 m, leaving it there for a while and then checking the temperatures like a freak to see where the thermocline was… this has become Stone Age in less than 30 years. Fish finding sonars were crude and exorbitantly expensive and required calibration every few weeks with cables on either side holding a bronze ball that will be progressively levered and the “bouncing” rate adjusted as needed… a total nightmare!

Communication and positioning safety… another area of incredible development… we just relied on VHF and, if lucky UHF radios for everything… my mother would not know anything of me for weeks at the time. The idea of the Internet on board was science fiction. Positioning was also very complex; all was dead reckoning, and I know how to use a sextant, which I will use to take the meridian at lunchtime if the sun was visible; the rest was just guessing, a bit later on the biggest boats we got the capacity to triangulate via coastal radio stations and Loran C… I remember vividly going over the manual of the first proper GPS I got (I was already fishing in the Pacific) and being bewildered by how much safety and efficiency this would bring, particularly as all this tech gets progressively cheaper as well.

Of this, of course, means that more and more vessels got built as things became cheaper and the “need” for fish got up. Fishing was a family / cultural job, with the odd one out like me… But back then, High Seas fisheries weren’t really a thing. Freezing technology hasn't changed so much, but it has become way more generalised, and crewing was primarily tied to nationals of the flag state plus highly protected by unions… I will come back to that later.

The number of boats exploded since then, chasing the same amount of fish initially and progressively less since then… we caught fewer fish overall because there were fewer of us, and we had less tech to find them even if the abundance was bigger…

I remember hitting a school of Southern blue whiting on a bottom trawl in the south of Argentina by chance (I could not really estimate biomass with the sounder, yet I knew that the bottom contour was good). In a few minutes, we packed the net all the way to the mouth; the boat slowed down while maintaining the same revs. We struggled to get the net to surface; all hydraulics were on the limit. I cleared the deck as the cables were at full tension. Once afloat, it was a monster; we could not bring it in, as the fully packed net was wider than the boat. The fish was so squashed that it was useless. I had to get on the inflatable dingy and cut the cod end open to let go of the catch… it was a nightmare. We lost a day and then had to repair the net for a further day. I don’t think abundance as such is typical today, even if all-around catch volumes may be way higher.

I guess I could go on and on and on…But let me focus on what I personally think has gone worse… or at least pissess me off the most

Big business and the Geopolitics of fish… fishing is not anymore about catching for others to eat (and making good money for the hardest and most dangerous job in the world). Fishing has become a huge business and, as such, so much more linked to politics both domestically and internationally… and with that, has taken on board what is, for me, the worst of politics in general and human behaviour in particular… hypocrisy.

I’m constantly biting my thong in meetings when I see statements, presentations, or read news by NGOs, industry associations, marketing people, eco-labels and private certifications on fisheries issues, and even more so when those delivering then as if it was the ultimate truth, are people that NEVER worked on fishing boat… it really gets me.

Let’s get the geopolitics first and its ugliest influence on fisheries: subsidies. I resume it with a principle of diplomacy “If you have a presence, you have rights”… so doesn’t matter is no way let’s say high seas LL does not make money, albeit paying shit to the crew and cutting maintenance and living standards… subsidies will support them because the benefit of being in the table, (i.e. having X amount of vessels there), outplays the cost of subsidizing fuel, giving tax exemptions, etc.…

The industry has become globalised. It is not just a former fisherman that had a few boats and became a fishing company…. It is a corporate business, and as such, like any other big business (from tech to wine and food), it takes advantage of ALL possible ( purposely made or not) shortcomings and loopholes in legislation, tax systems, crewing rules, etc.… Compounding to this, the regulatory framework in the HS was made when there really wasn’t a High Seas industry… so when you have these gaps (as dictated by capitalism), business runs rampant. And this is just not fishing in every industry, so here is one thing that REALLY pisses me off… fishing gets rightly pointed out for many things (around environmental and social impact, tax evasion, etc), but in a way as if it exclusively a fishing problem… and is not is all around us in every industry as soon as you peeling layers.

Example: bottom trawling has environmental impacts, no doubt about it, and the gravity of these impacts depends on many issues, ranging from the benthos in which they happen to the species being trawled… is not “one size fits all”. And then I heard: imagine 2 bulldozers going over a forest and destroying all… and I looked outside my house, I look at farms, roads, sports fields, etc., and that is what literally happened! There were forests there at some stage not so long ago! A field of soybeans has a biodiversity impact of 100%... everything there was killed and removed to plant an exotic species. So where are the “stop agriculture” or “stop housing development” coalitions?

And another I rant on usually: high seas transhipment in the WCPFC, textbook geopolitics-driven hypocrisy.

And the hypocrisy doesn’t stop there… politics and business drove colonialism up to the 1980s and still drive the more subtle neo-colonialism today. I see a direct line between many NGOs, eco-labels, private certifications, some “developing” programmes, etc., with “white (or perhaps rich country) saviourism” as the latest expression of the colonial mindset.

But let me focus the end of my rant on what has definitively gone worst as the consequence of all the above of the above:

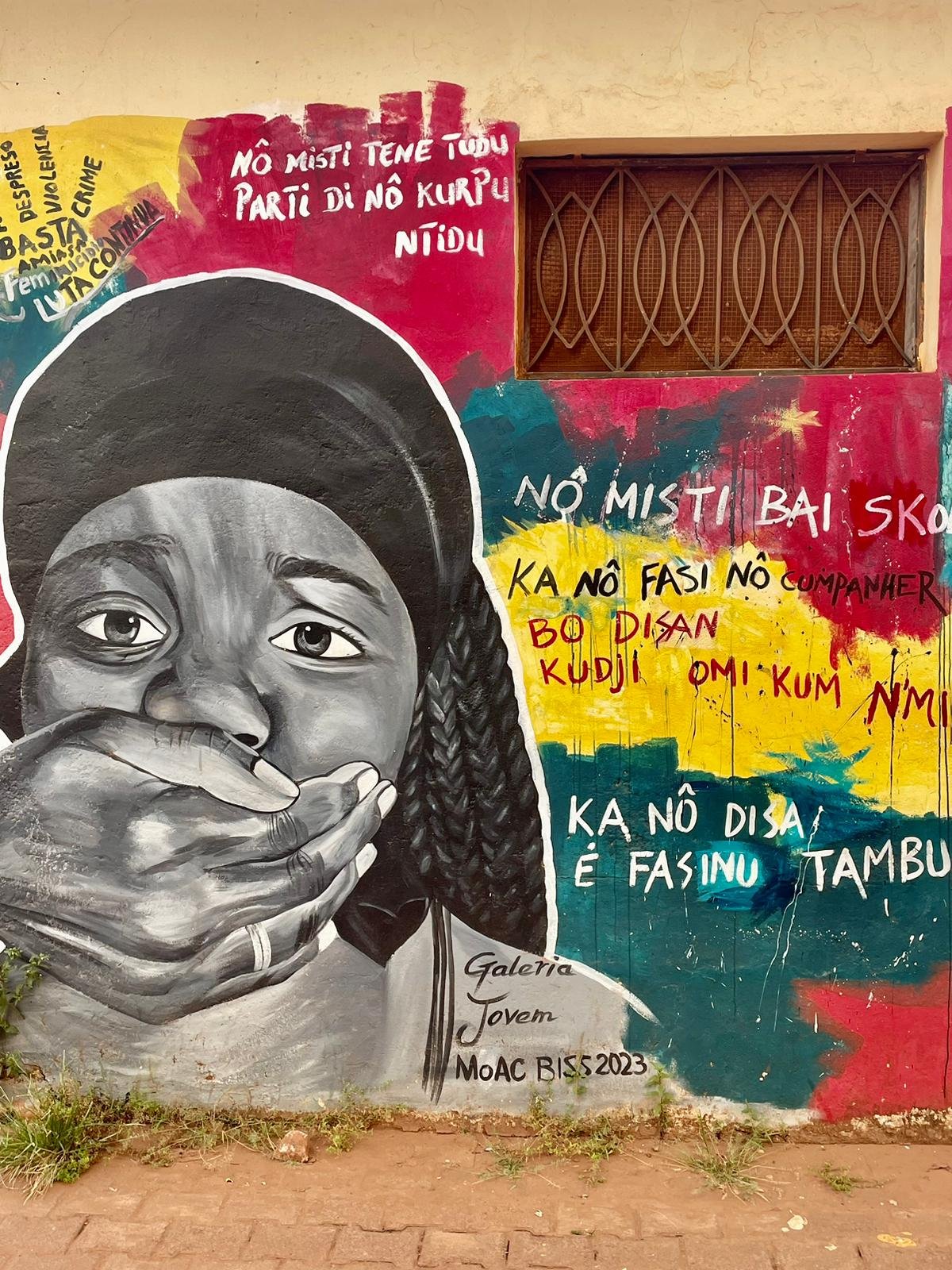

The fisherman's income and rights are worse today than 40 years ago… and this is so soul-destroying for me personally, to the point of wanting me to walk off the only job I ever had.

The whole edifice of fishing, from boatbuilders to bureaucrats at RFMO meetings, from truck drivers picking up fish to politically appointed ministers of fisheries, from marketing people in the industry to NGO activists, from eco-labels to fisheries students, and so on… has grown immensely and become so much richer in the last 3-4 decades than it was before. All these people (in 99% of the cases, never worked on a fishing boat), and all their jobs, and all industries associated with them, depend for their existence on fisherman… and their income and life perspectives has gone down since then instead of up like the rest.

There is no way that an 18-year-old kid like me then will get today for the first time on a fishing boat, could do the path I’ve taken to get here and be writing this (while taking a break from my present work for the World Bank, the EU, FAO and NZ MFAT), and that saddens me a lot.

The whole business/politics/certification empire has risen on the backs of people, which is worse at all levels than 40 years ago. A union protected my rights, and my income was based on standardised agreements and catch shares. I could take breaks for exams, I would earn enough to live while having access to a decent education and health system, and the flag in the back of the vessels did actually mean something… all that is gone for someone starting today in most (if not all countries in the world).

For example: I sit on meetings for crewing CMM at an RFMO, and I only see people who have NEVER worked on a fishing boat, trying really hard to find red herrings in an already diluted text; it seems that they are just basically being opposed to act as decent humans and grant fisherman rights, protections and payments that they will not even think in denying their children. Nothing being asked in the discussion papers in front of them are requirements that the states they represent should already comply with under UNCLOS and ILO for their merchant vessels, and they act as if we are asking them to sell their organs.

This is the tragedy of fisheries in my 40 years in it… we created an empire, and like all empires, it was built on the back of those at the basis of it… the essential workers, the fishermen. They are worse instead of better than when there wasn’t an empire, and that is just not right.

So yeah…, it is not a happy 40th anniversary, unfortunately. I owe my life to fisheries, yet I find myself increasingly struggling in the moral no-man lands in between cynicism and mercenaryism, the exactly two aspects of my work I struggle with the most… mainly because those two aspects are the basis of the two “attitudes” I dislike the most in people, and fight hard to never fall into as a person: they are ingratitude and pretentiousness. Yet, booth seems to abound in the circles I move today.

In any case, thanks for reading if you made it all the way here.