I have been going on and writing about subsidies for a while now… so I have a “natural” interest in reading about them particularly when people I know are involved. And this was the case on this paper where I know Megan Bailey [who was behind one of my favourite papers ever – (that must be the ultimate nerd statement)] and Anthony Rogers whom I met while he worked at PEW in DC, the other thing that attracted me to the paper was that they named a section with the title of this blog.

I read it, I liked it, so I decided to paste that section below… yet as I always say: read the original.

Subsidies are quite a topic, as the international community is in the final stages of negotiations to achieve a target of the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDG 14.6),namely, ending harmful fisheries subsidies. The original deadline of June 2020 is currently delayed due to global responses to the Covid-19 pandemic, but an agreement is expected to be reached once normal activities resume. Plenty is written about subsidies as does touch many areas in fisheries and well-documented. Overcapacity (the existence of more fishing power than needed to take the maximum sustainable yield) is perhaps one of the most well-known, as it leads to overfishing where management is lacking and to economic waste in any case.

This lost potential value due to overcapacity is estimated at ~ US$83 billion per year, but also can create conflicts with legal fishers who see little benefit in abiding by the rules… and this latest issue is an “immense” area that I imagine must be hard to research, as evidence relies on almost “personal” stories…

So here is part of my story touched by the subsidies of others: back in the late 1990s -early 2000s I was still mixing consulting with commercial fishing and we in NZ had at some stage 5 purse seiners fishing in the pacific Sanford had 2, Talley’s had 2 and Simunovich had one: the Ocean Breeze and she was the one I used to fish. (see me with the Madeira guys in the pic)

We circulated the Pacific (as the others vessels) accessing the HS and the EEZ of coastal states via paying access through bilateral negotiations. The first times I was in many of the ports I work now (Majuro, Pohnpei, Tarawa, Funafuti, Rabaul) was transhipping there.

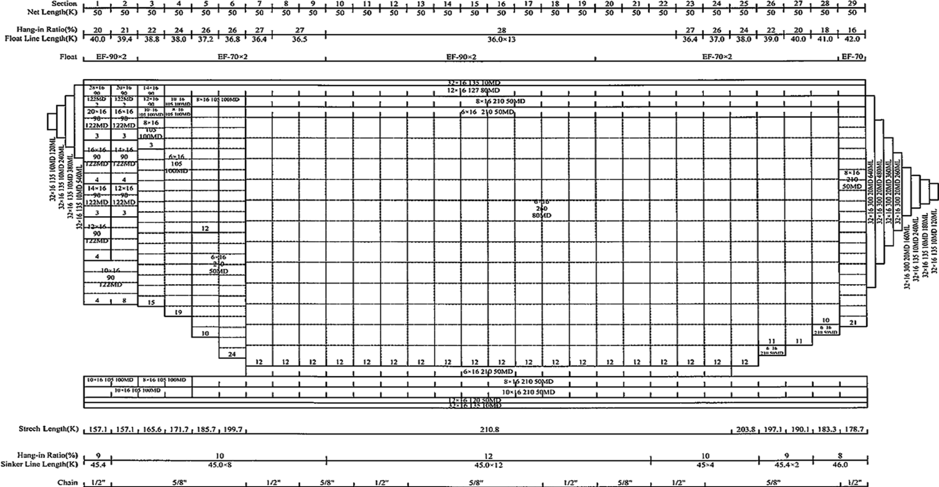

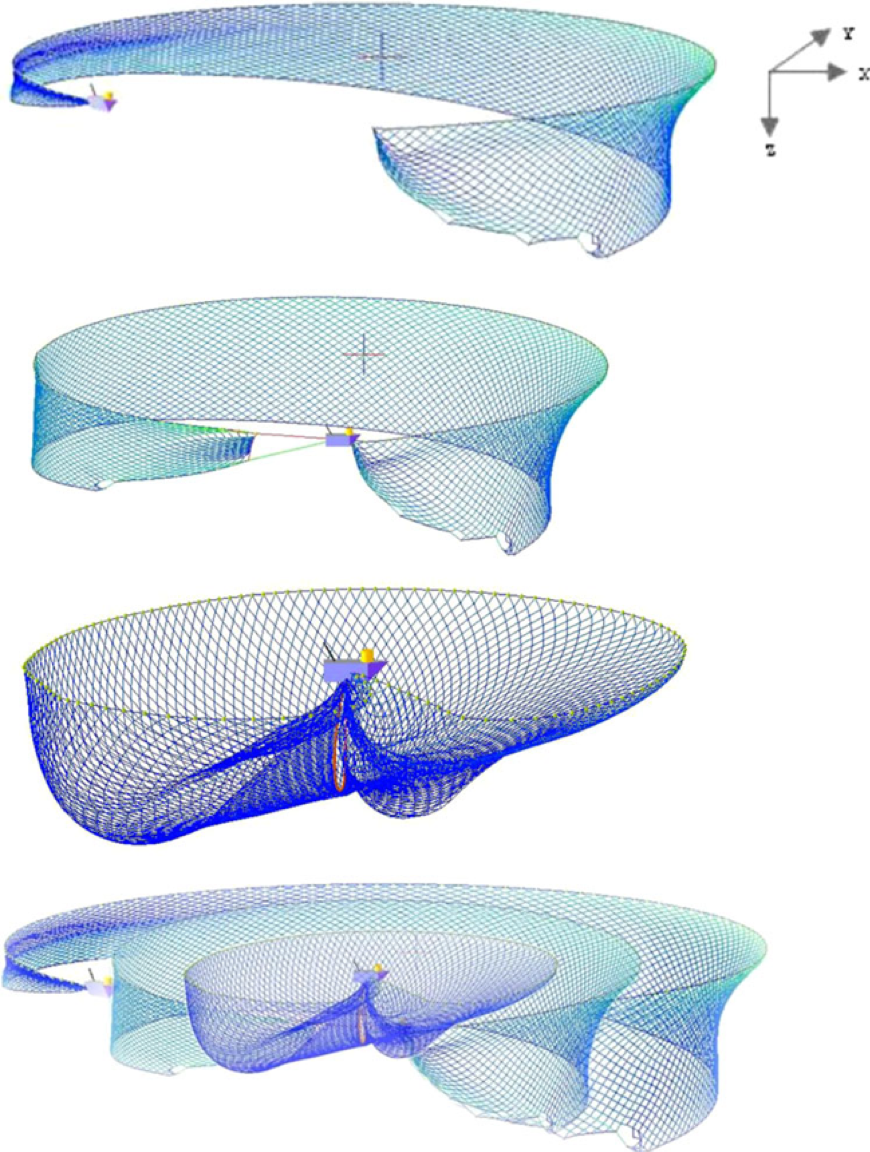

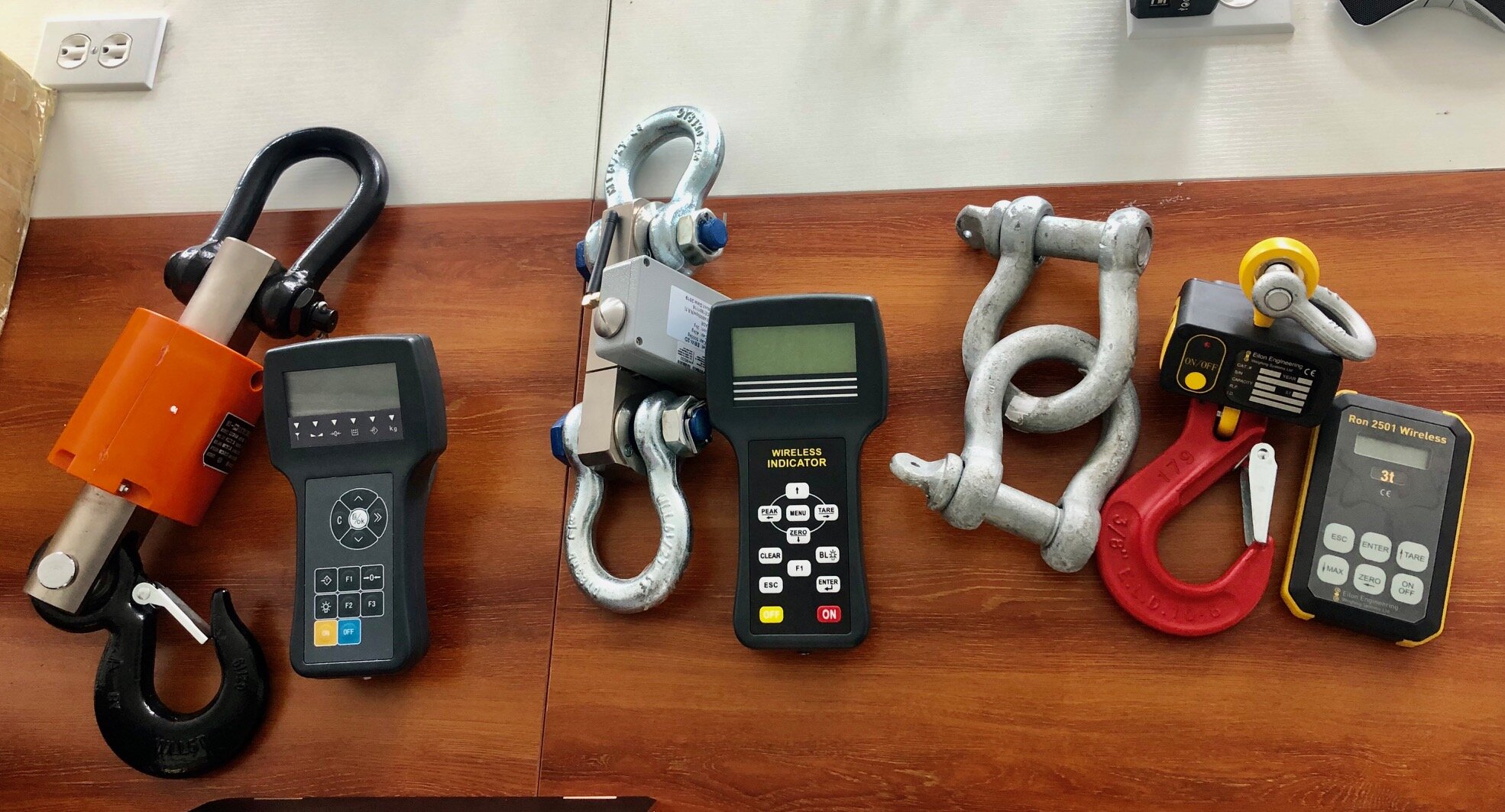

Part of my job (called then “navigator”) was to guess (with the captain) where the fish was, with the tools we had at the time: very expensive satellite imaging and identifying water mass fronts, primary productivity, and other oceanographic indicators I was familiar with, playing with the bird radars and beam sonars, but also i was quite keen in listening to the most experienced crew members (we had 3 guys from the same family in Madeira island, that were 8th generation tuna fisherman - walking tuna encyclopaedias)…. also spending a lot of time on the radio talking to other boats (all of the “western” captains knew each other then)… but mostly it was spending a LOT of time looking onto the horizon… (no wonder my eyes are failing and my back is dodgy!!)

Btw… the navigator job barelly exist anymore since now everyone has FAD sonar buoys so fishing is kind of drawing by numbers… other than when is FAD closure and then you see vessels being out for 40 days and come 1/2 full, since a lot of that fishing knowledge is not on board anymore

Anyway… I also was at the time also working on my 2nd MSc (working on improving selectivity in snapper longlining via a purposely designed bait) here in NZ, so I will work for a couple of months and head back for exams… I wasn't sure if the consulting thing will take off, so fishing was still a good backup option that I enjoyed.

In any case, it was a good time, money was ok, fuel was cheap, tuna prices was ok, life on board was easy, good food, interesting people… I worked with mostly Croatians, Kiwis and Portuguese (from Madeira and the US), but also Peruvians, Ecuadrians and Philippinos. As we were in NZ flagged vessel, the non-kiwis on board had NZ work permits -getting them was also part of my job, as i knew the system- and got paid NZ salaries and the option to be part of the NZFIG (the NZ fisherman’s union).

But times were changing from various fronts, the increasing push of the Asian fleets, the advent of substantial reflagging from the same Asian fleets to countries that did not have the requirements of having official visas and paying conditions as part of their flagging requirements (or changes in the national legislation to lower those need - like in the US vessels where no one has green cards). Then also fuel prices starting to climb, more vessels implied more fish available wich brought tuna prices down, and so on.

All this made staying competitive very hard since there was an unfair playing level, the rest of the fleet had various level of subsidies an NZ does not has any. And then when the Vessel Day Scheme came in (for all the right reasons), it just became increasingly impossible to make money without fully eroding the main costs onboard: crew wages and fuel. Not surprisingly, there is only one NZ PS fishing now, and quite marginally… mostly in the high seas and the northern fringes of the EEZ, and it belongs to NZ most ruthless operators in terms of fisherman’s earnings.

Hence the present fleet fishing the pacific is mostly operated by countries that are massive subidesiers of their fleets and their vessel owners that flagged away, either directly or indirectly, through massive fuel subsidies and operate 99 % with crew not related to the flag, that does not have the same labour and earning rights that the citizens of the flag state and so on…

So is not I big stretch to link subsidies to unfair level playing field, and a straight line to the present levels of labour abuses in some cases, and human exploitation pretty much in all cases (a Indoesian deckhand makes 350US a month, a westerner may be around 1500 plus catch shares for the same job).

Obviously, being very lucky to have accessed education (and being part westerner) I took further the consultant path, and I didn’t come back to fishing commercially since then… the subsidies of others changed my life… and this leads perfectly to the chapter on my colleages paper:

Supporting fishers (not fishing) does not require harmful subsidies

Nations must be able to support fishers and fishing sectors when necessary, and there are many alternatives to harmful subsidy programs. Based on past examples from fisheries and other sectors, strategies with best results reorient subsidies away from capacity-enhancement and towards co-management, and/or condition them on clearly enforced, sustainable actions.

Decoupling subsidies from fishing (e.g., cash transfers) can be very useful but requires careful design and implementation. Buybacks to reduce fishing capacity tend to fail due to seepage back into harmful practices or capture by unintended actors.

Fundamental principles for any beneficial subsidy program include clear short- and long-term goals, co-design with fishers and other stakeholders, transparent design and implementation, and political will that recognizes long-term community needs and honors national and international commitments.

The specific mechanisms of new fisheries support programs will depend on local contexts, but it is essential that subsidies aim to support fishers, not just fishing per se. Receiving cheaper fuel or better gear requires fishers to fish more, when they could instead choose to use financial support towards livelihood improvements such as households, nutrition, education, etc., that enhance well-being in the long-run. Such programs can be more cost-effective than common harmful subsidies such as fuel, which can increase fisher income by less than 10 cents for every dollar spent .

Reforms can take a portfolio approach with a diversity of programs. For example, conditional cash transfer programs could be used in the short-term to incentivize participants (e.g., vessel owners, license holders, and fish workers) to undertake actions aligned with broader societal goals. This can include payments for monitoring or restoration initiatives that help enhance coastal resilience or rebuild fish stocks (SDG 13.1 and 14.2).

At longer time scales, subsidies could support desired transitions across seafood-related industries (e.g., improved management systems, reduction of post-harvest loss, value-added processing) or into new activities.

Countries subsidizing distant-water fleets could shift to supporting fisheries management in other nations to enable their participation in markets, with the same outcome of sourcing seafood while increasing incomes of local fishers, provided exports do not reduce local accessibility of seafood and associated micronutrients for coastal populations. Such ‘onshoring’ _of foreign fishing could also reduce transshipping and contribute to enhanced monitoring, transparency, and management. Many fisheries subsidy programs are a legacy of top-down development approaches, and reforms must be co-designed with communities and key stakeholders so that their needs and values are appropriately represented.

An effective agreement to end harmful fisheries subsidies is an added opportunity to address important challenges in supporting fishing economies. For example, downstream fish workers have historically not received subsidies directly but must be included in sectoral reforms. Governance of high seas fisheries is also a controversial issue including large differences in monitoring and management effectiveness across species and regions , which have led to calls to close the high seas to fishing .

Subsidies that result in overcapacity can undermine the conservation mandate of Regional Fisheries Management Organizations (RFMOs) within their convention areas. Thus, while subsidies may be seen as a domestic issue for nations, they are not a trivial contributor to non-cooperation, and improved efforts towards transparency and accountability must be extended towards subsidies as well.