FFA has published many landmark publications done by very capable colleagues over the years. These are publications I keep referring back to since they are wide in scope and thoroughly researched. My very well respected colleagues (and very nice people) Mike McCoy, Antony Lewis, and Liam Campling have just released a new jewel, and I'm sure is going to be one of those reports I keep coming back to. An excellent study is available for download here.

This report provides industry and market intelligence regarding the current status of the tuna longline industry in terms of distant water fleets (DWF) and other companies involved in the global value chains that these fleets supply. The study examines the DWFs of China, Japan, South Korea and Taiwan. The primary focus is on industry dynamics, that is, key companies and organisations, industry organisation and corporate strategies; and the secondary focus are on markets and marketing strategies.

I quote below some of the key messages I found:

In 2015, the total global longline tuna catch was around 450,000 mt. WCPO accounted for around 56%, EPO 16%, AO 15% and IO 13%. Bigeye accounted for 38% of total global catch by species, yellowfin 30% and albacore 32%. Except for 2012 when global longline catch exceeded 500,000 mt, annual catches were fairly stable at around 450,000-460,000 mt during 2011-2015.

The most significant distant water longline fleets operating in WCPO (and EPO) are China, Taiwan, Korea and Japan in terms of fleet size, catch volumes, and bigeye catch quota allocation (hence, these four countries were selected as case studies for this study).

Collectively, China, Taiwan, Korea and Japan’s longline vessels have accounted for 75-83% of the total number of longliners active in the WCPO from 2011-2015.

In the WCPO, there are two longline fisheries – the southern and tropical longline fisheries. The tropical longline fishery typically consists of large-scale distant water vessels fishing between 20ºN-20ºS, which target bigeye and yellowfin for sashimi markets, with smaller volumes of incidentally-caught albacore. Vessels operating in the southern longline fishery are typically smaller (<100GT) and target albacore for canning markets in sub-tropical waters below 10ºS and have small volumes of incidental bigeye and yellowfin bycatch.

With advancements in freezer technology, particularly for smaller vessels, the distinction between tropical and southern longline fleets has become less noticeable. Some vessels now can switch targets depending on seasonality, fishing location, stock abundance, and other factors, moving between both fisheries. The southern longline fishery has developed significantly over the last 10-15 years, mainly in association with growth in the number of Pacific Islands’ domestic-flagged and chartered longline vessels.

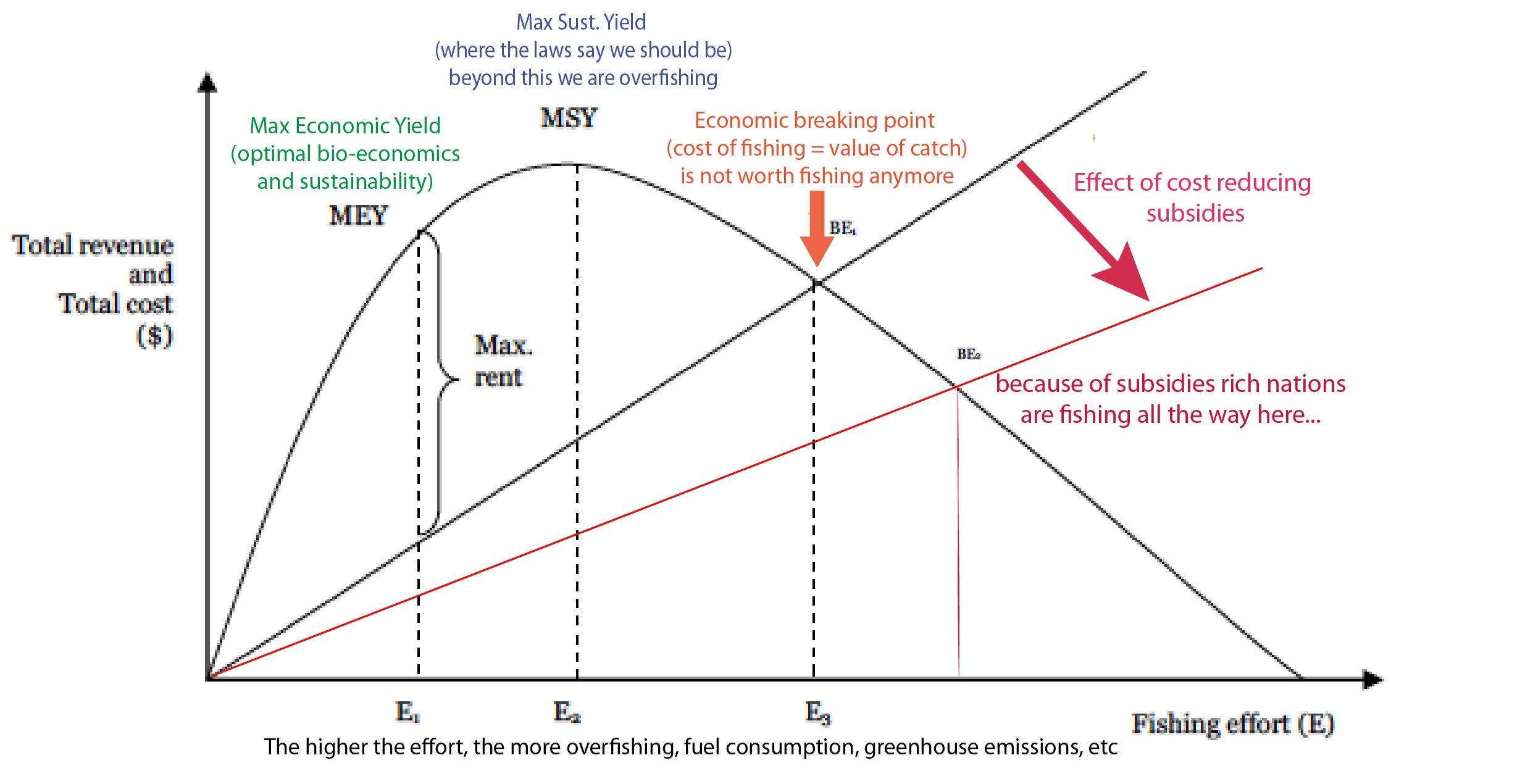

The WCPO tropical longline fishery has had a long-term trend of below-average economic conditions, which has resulted in a declining number of vessels, particularly distant water vessels from Taiwan, Korea and Japan. It is projected that the fishery will continue to follow a declining trend from 2017 to 2026, resulting from a forecasted increase in fuel cost and a decline in catch rates, primarily bigeye, which will more than offset projected above-average fish prices.

Economic conditions for the WCPO southern longline fishery have also declined. Persistent low catches continue to impact negatively and, if prolonged, will result in below-average economic conditions for the fishery in the coming years.

High seas transhipment of catch is the norm for authorised vessels in the large-scale tropical longline fishery that spans both the eastern portions of the WCPO and EPO. The large Japanese, Korean, Chinese, and Taiwanese vessels in this fishery spend up to a year or more at sea, obtaining fuel from tankers at sea, as well as bait and various supplies from refrigerated carriers. These practices are integral to the economic viability of the fishery, where fishing activities take place over a wide range of the WCPO and EPO, often in areas that are far removed from ports that might otherwise be used for transhipment. However, there are concerns that given challenges relating to monitoring, control and surveillance, high seas transhipment increases opportunities for illegal activities, such as IUU fishing, human trafficking and smuggling.

Regulatory mechanisms shaping industry operations are layered. They work at multiple scales – regional, sub-regional and national – and at multiple points in the global value chains for longline products. The Western and Central Pacific Fisheries Commission (WCPFC) has a number of conservation and management measures (CMMs) in force which apply to the WCPO tropical and southern longline fisheries. The Conservation and Management Measure for Bigeye, Yellowfin and Skipjack Tuna (CMM 2016-01) is the primary management measure for tropical tuna stocks in the WCPO, establishing flag-based longline bigeye catch limits and requiring WCPFC commission and cooperating non-members (CCMs) to take measures to not increase longline yellowfin catches. CMMs (other than small-island developing states and Indonesia) are also required to not increase the number of longline vessels targeting bigeye above 2010-2012 levels. The Conservation and Management Measure for South Pacific Albacore (CMM 2015-02)requires CCMs to not increase the number of their vessels actively fishing for South Pacific albacore south of 20°S above 2005 levels or average 2000-2004 levels.

At the sub-regional level, in 2014 eleven Pacific Island countries agreed on text to establish the Tokelau Arrangement (TKA). The TKA is a voluntary in-zone-based management arrangement for the South Pacific Albacore Fishery comprised of a Catch Management Agreement (CMA) for longline vessels fishing within their Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZs) for South Pacific albacore, as either a target species or as by-catch. The CMA has been actively negotiated since 2014 and is nearing the stage where each member will need to make critical decisions whether to bring it into force or not. It provides for the setting of an overall Total Allowable Catch (TAC) and allocation of that TAC amongst parties.

In 2014, the Parties to the Nauru Agreement’s (PNA) Longline Vessel Day Scheme (LL VDS) also came into effect under the Palau Arrangement. As PNA waters largely fall within the WCPO’s tropical zone (20°N- 20°S), the LL VDS is a management scheme covering the tropical longline fishery, targeting bigeye and yellowfin. The LL VDS establishes a total allowable effort level (TAE) for fishing in all parties’ waters, which is then allocated amongst the parties as party allowable effort (PAE). Following a trial period for several years, the LL VDS was formally implemented on 1 January 2017. At this time, seven out of eight PNA members had signed on as participants, plus Tokelau.

In recent years, labour standards in the fishing and fish processing sectors have gained increasing attention, particularly with the uncovering of serious human trafficking and labour rights abuses in Thailand’s seafood fishing and processing sectors. This has prompted major players in the industry, including US and EU retailers, brand owners, processors and traders, as well as governments to respond. Labour issues will be particularly challenging to address for large-scale distant water longline fishing vessels which are away at sea for long periods (up to 18 months at a time), employing foreign crew who work very long hours under difficult conditions.