Over the past few years one of the biggest questions in climate science has been why, since the turn of the century, average surface-air temperatures on Earth have not risen, even though the concentration in the atmosphere of heat-trapping carbon dioxide has continued to go up.

This “pause” in global warming has been seized on by those sceptical that humanity needs to act to curb greenhouse-gas emissions or even (in the case of some extreme sceptics) who think that man-made global warming itself is a fantasy.

People with a grasp of the law of conservation of energy are, however, sceptical in their turn of these positions and doubt that the pause is such good news. They would rather understand where the missing heat has gone, and why—and thus whether the pause can be expected to continue.

The most likely explanation is that it is hiding in the oceans, which store nine times as much of the sun’s heat as do the atmosphere and land combined. But until this week, descriptions of how the sea might do this have largely come from computer models. Now, thanks to a study published in Science by Chen Xianyao of the Ocean University of China, Qingdao, and Ka-Kit Tung of the University of Washington, Seattle, there are data.

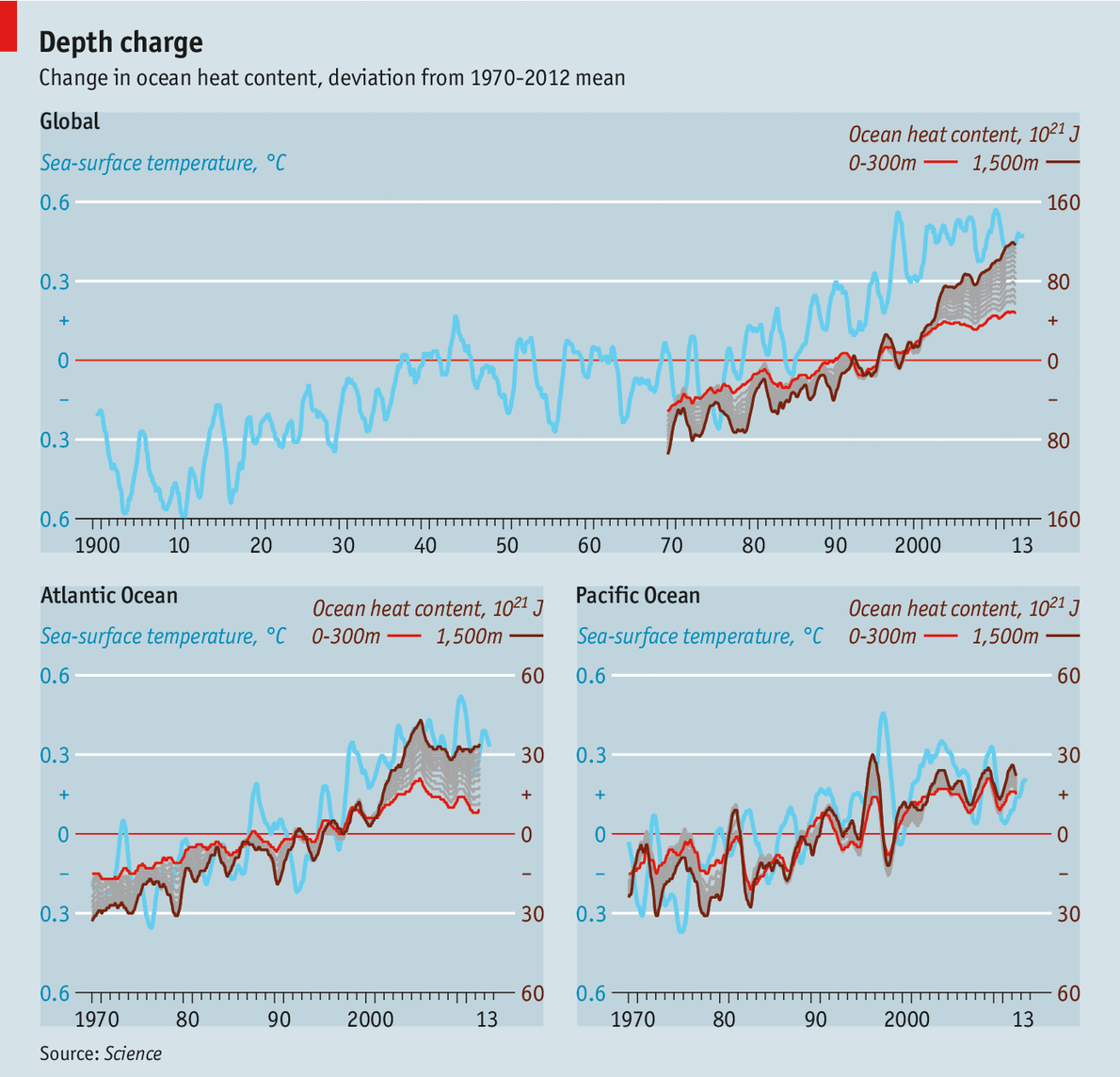

Dr Chen and Dr Tung have shown where exactly in the sea the missing heat is lurking. As the left-hand chart below shows, over the past decade and a bit the ocean depths have been warming faster than the surface. This period corresponds perfectly with the pause, and contrasts with the last two decades of the 20th century, when the surface was warming faster than the deep. The authors calculate that, between 1999 and 2012, 69 zettajoules of heat (that is, 69 x 1021 joules—a huge amount of energy) have been sequestered in the oceans between 300 metres and 1,500 metres down. If it had not been so sequestered, they think, there would have been no pause in warming at the surface.

Hidden depths

The two researchers draw this conclusion from observations collected by 3,000 floats launched by Argo, an international scientific collaboration. These measure the temperature and salinity of the top 2,000 metres of the world’s oceans. In general, their readings match the models’ predictions. But one of the specifics is weird.

Most workers in the field have assumed the Pacific Ocean would be the biggest heat sink, since it is the largest body of water. A study published in Nature in 2013 by Yu Kosaka and Shang-Ping Xie of the Scripps Institution of Oceanography, in San Diego, argued that cooling in the eastern Pacific explained most of the difference between actual temperatures and models of the climate that predict continuous warming. Dr Chen’s and Dr Tung’s research, though, suggests it is the Atlantic (see middle chart) and the Southern Ocean that are doing the sequestering. The Pacific (right-hand chart), and also the Indian Ocean, contribute nothing this way—for surface and deepwater temperatures in both have risen in parallel since 1999.

This has an intriguing implication. Because the Pacific has previously been thought of as the world’s main heat sink, fluctuations affecting it are considered among the most important influences upon the climate. During episodes called El Niño, for example, warm water from its west sloshes eastward over the cooler surface layer there, warming the atmosphere. Kevin Trenberth of America’s National Centre for Atmospheric Research has suggested that a strong Niño could produce a jump in surface-air temperatures and herald the end of the pause. Earlier this summer, a strong Niño was indeed forecast, though the chances of this happening seem to have receded recently.

But if Dr Chen and Dr Tung are right, then the fluctuations in the Atlantic may be more important. In this ocean, saltier tropical water tends to move towards the poles (surface water at the tropics is especially saline because of greater evaporation). As it travels it cools and sinks, carrying its heat into the depths—but not before melting polar ice, which makes the surface water less dense, fresh water being lighter than brine. This fresher water has the effect of slowing the poleward movement of tropical water, moderating heat sequestration. It is not clear precisely how this mechanism is changing so as to send heat farther into the depths. But changing it presumably is.

Understanding that variation is the next task. The process of sequestration must reverse itself at some point, since otherwise the ocean depths would end up hotter than the surface—an unsustainable outcome. And when it does, global warming will resume.

Original source here.