The Boston Globe, published a interesting article by Latif Nasser on this subject and quotes Blaise Kuemlangan a friend from PNG whom we worked together in Rome. Here I quote the parts I found more interesting from the original.

So far, the world’s attention has rightly focused on how much these places have to lose: their homes, their communities, their cultures, their vistas. But these countries have another, less visible set of assets at stake as they consider their survival—assets that won’t necessarily be lost, but which raise substantial questions. These are their large and valuable maritime zones.

Countries like Kiribati gained control over their surrounding oceans under the UN Law of the Sea, adopted in 1982, back when the prospect of a drowning nation seemed far-fetched. The law granted every country with a coastline economic domain over water 200 nautical miles (230 miles) off its shore, a descendant of the 17th-century “cannon-shot rule,” which gave nations authority over as much water as they could defend with coastal artillery.

These substantial economic rights belong to inhabitable islands, but generally not to—to use the technical term—rocks. The UN has strict criteria to tell one from the other. An island must be “naturally formed” and higher than high tide; part or whole of a nation recognized by other nations; and a place that can “sustain human habitation or economic life of [its] own.” If it doesn’t meet those criteria, it is a rock, and doesn’t merit territorial rights.

When it comes to nations like Kiribati and Tuvalu, however, the patch of ocean largely is the country. Tuvalu’s ocean-to-land ratio is 34,600 to 1. It would be more accurate to think of them not as small island states with a claim on the ocean, but rather as gigantic ocean states with a patch of land in the middle.

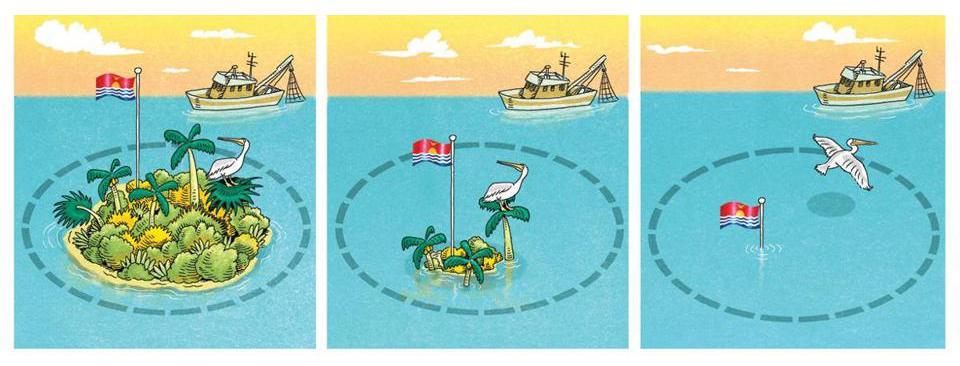

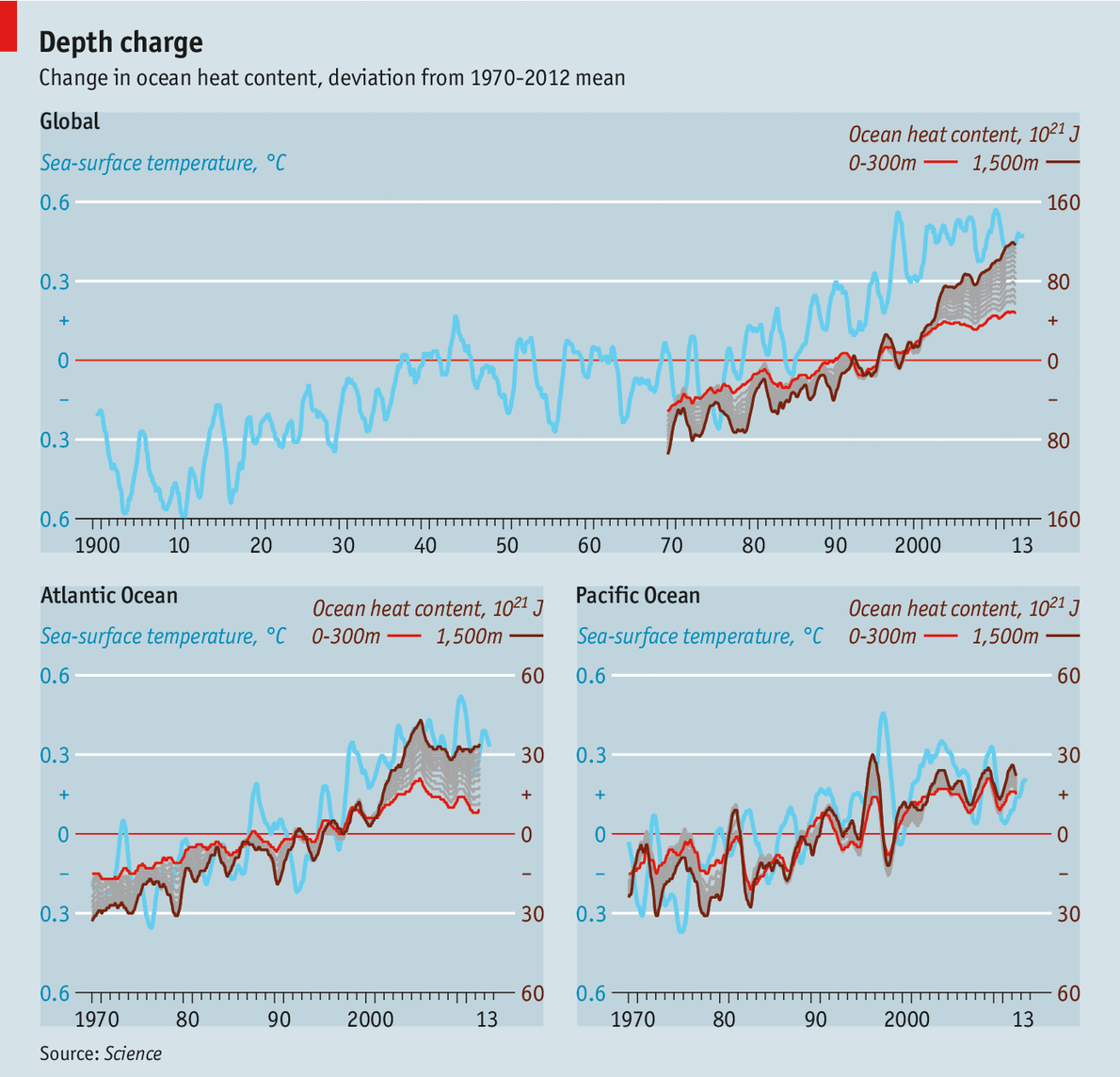

In the decades to come, many low-lying nations will start to look more like uninhabitable rocks. Wave “over-wash” will degrade the fragile lens of fresh groundwater, leaving residents dependent on rain or imported bottled water. The warming ocean will result in degradation and bleaching of reef ecosystems that protect the islands from erosion. The elevating sea level—rising as much as a meter by 2100, according to last year’s IPCC report—may inundate the lowest-lying islands of archipelagos such as the Maldives (average elevation 1.6 meters), Tuvalu (1.83 meters), Kiribati (1.98 meters), and the Marshall Islands (2.13 meters).

If these islands do become rocks, the question of their maritime holdings is complex, as they’re inhabited and have their own seats at the United Nations; they also draw a significant portion of their gross domestic product from those ocean rights. According to the UN’s International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights, “In no case may a people be deprived of its own means of subsistence.”

As long ago as 1990, a scattering of international law scholars began to imagine approaches to the problem, including ones that might even help threatened nations with their resettlement efforts.

One early proposal from Fred Soons of the Utrecht University School of Law is a solution that is part physical and part legal. Soons assumes that the islands’ adaptation efforts will include man-made barriers, and perhaps in the long run, even more ambitious efforts that amount to artificial islets. In that case, he suggests broadening the legal definition of “naturally formed” islands to include such land-preservation efforts. In other words, so long as an island was initially natural, Soons believes it ought to count as an island, even if it later becomes enhanced—and even potentially supplanted—by artificial components. (Soons points to the example of Okinotorishima, a remote atoll that Japan has spent more than $700 million to protect with steel blocks and concrete embankments, though its claim to islandhood—and the surrounding ocean—remains contested by neighbors.) Even Soons himself doesn’t see this as a permanent solution, however: Artificial barriers simply delay the inevitable, and the price tags for buttressed or artificial islands are, to use the IPCC’s words from 2007, “well beyond the financial means of most small island states.”

Other legal scholars have focused on ways that the maritime territory can be preserved as a national asset even if the people leave. Several, including UC Berkeley School of Law’s David Caron, have observed that changing sea boundaries aren’t just a problem for islands: The rising ocean promises to redraw every coastline on the map. Instead of constantly updating maps every time a beach is submerged, they suggest, why not freeze the boundaries in place? For low-lying islands, this would mean that the sea as currently measured around Kiribati would become the permanent patrimony of its people—and wherever in exile they end up, the population would continue to receive royalties from its former coastal waters.

Rosemary Rayfuse of the University of New South Wales in Australia takes a different route to a similar outcome. “An equitable and fair solution,” she writes in a 2013 anthology documenting a Columbia University conference on Threatened Island Nations, “would be the recognition in international law of a new category of State, ‘the deterritorialized state.’” Rayfuse argues that the creation of such a category would enable island nations—even if they lost their land—to keep both their nationhood and their maritime zones, despite not having a piece of land to call home. Remarkably, such a landless state does exist today. The Knights of Malta (not to be confused with the country of Malta) are a 900-year-old lay Catholic order who today have no land, but do have a nonvoting seat at the United Nations. Their example, Rayfuse suggests, provides a seamless way to incorporate submerged nations into the international community.

The main hitch to both of these plans—frozen baselines and deterritorialized states—is that they depend on international legislation, which is notoriously slow and unwieldy. The UN Law of the Sea’s amendment procedure, for instance, has never been used. Nor does it help that the island nations have little geopolitical clout. Rayfuse noted in 2013 that “freezing baselines does not appear to be high on the international agenda at the moment.”

There’s a final strategy for these island nations to be able to keep their maritime zones, a strategy that doesn’t depend on sea walls or international legislation. Rayfuse called it “the most straightforward and appealing solution” to the maritime zone dilemma. If each island nation can find a friendly neighboring nation willing to sell it some territory, it can move to that territory and continue to operate its preexisting maritime zones, so long as any part of the island is still above water. Kiribati’s president announced earlier this year that at Fiji’s invitation, his country had purchased land from the Anglican Church on Fiji’s second-largest island as part of an effort to migrate with dignity.

A major catch with this strategy is that few countries are willing to swallow whole another country, and those that are often want something for themselves out of the deal. In 2001, when Tuvalu approached Australia and New Zealand for some land, Australia rejected the deal out of hand. New Zealand agreed to host only those Tuvaluans who were under 45, spoke English, and had a job offer in New Zealand—requirements that excluded approximately 9,000 of the 11,000-person country. Even Kiribati’s recent land deal has come under suspicion; Atlantic reporter Christopher Pala visited the plot of Fijian land that Kiribati bought for $8.7 million, and found that the land was too small to feed or house Kiribati’s population, and that in fact, the land was already inhabited.

If they cannot find deals on better terms, these island nations may have to merge with neighboring nations, using their valuable maritime rights as a bargaining chip. In effect, it would be a flat-out trade: asylum for control of the maritime zones.

These strategies—redefining “natural,” freezing maritime zones, creating deterritorialized states—amounts to a kind of thought experiment, a radical tweak to our idea of how fixed nations are and should be.

It’s not clear when islanders will need to turn these thought experiments into real-world legal strategies. Some geoscientists project that coral reefs supporting atoll islands will grow along with rising seas, meaning that only those living close to shore will lose their homes; parts of the atolls may actually rise as other parts sink. Other researchers claim that regular flooding, food insecurity, and lack of fresh water will render the islands uninhabitable sooner rather than later. Whatever the timeline, as Rayfuse put it in an e-mail, “there is a presumption of the continuity of states, and the international community will deal with the issue of disappearance if and when it happens.”

At the moment, the value of their maritime assets seems to be going up: The United States recently purchased its 2015 tuna fishing rights from a collective of Pacific island nations for $90 million dollars, up from the $21 million it paid in 2009. There’s also more than money at stake—by law, islands can use their control of the zones to enact environmental standards, though they are too small and resource-strapped to enforce them without help.

For now, the island nations face the first and most basic step to securing their maritime zones: mapping them. To chart out existing ocean borders now would shore up their claims as their outlying islands become uninhabitable and their zones begin to shrink. Even this is far from trivial: An exact surveying effort involves extrapolating outer limits from base-point coordinates on shore, negotiating any overlaps with neighboring countries, and then formally depositing them with the United Nations in New York, a project beyond the technological and financial capacities of most island countries.

Blaise Kuemlangan, who works for the FAO and encourages Pacific Island nations to map their boundaries, expects that—unless the countries themselves or the international community make a special effort now—mapping will not be completed for at least another 20 years. By then, these islands will most likely still be inhabited. But they’ll need, even more urgently, to understand exactly what they have to trade for their future.