Marine Pollution issues are “governed” by MARPOL 73/78 is the International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships, 1973 as modified by the Protocol of 1978. ("MARPOL" is short for marine pollution and 73/78 short for the years 1973 and 1978.)

It was developed by the International Maritime Organization in an effort to minimize pollution of the oceans and seas, including dumping, oil and air pollution. The objective of this convention is to preserve the marine environment in an attempt to completely eliminate pollution by oil and other harmful substances and to minimize accidental spillage of such substances.

From my time in the fishing boats and from the workbooks I see from SPC/FFA fisheries observers that include a Regional Observer Pollution Report Form GEN-6 (See at the end of the post for an example). I assumed the issue must be substantial, even if nothing gets done with the findings (a bit like compliance issues). And unfortunately… I wasn’t wrong.

At last years WCPFC TCC (Technical and Compliance Committee) and group of SPREP lead by Kelsey Richardson presented a report on the issue. I quote it in the post… the original is here.

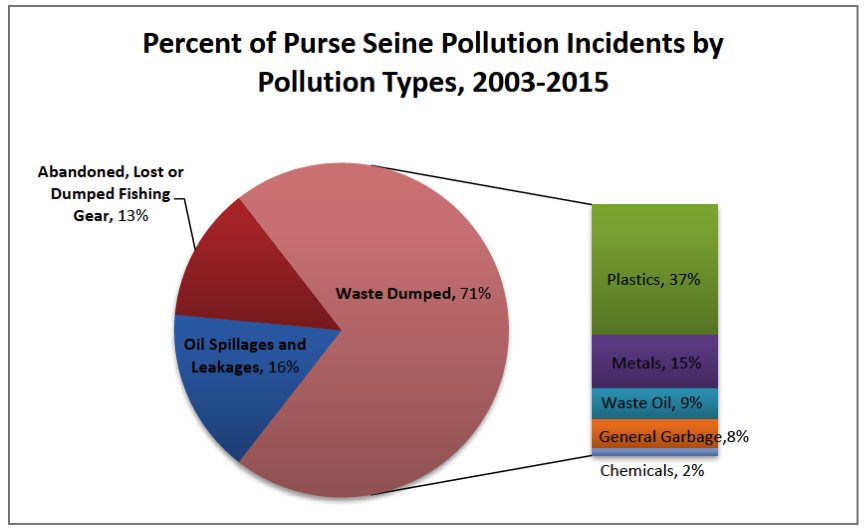

The report examines more than ten years of collected data on more than 10,000 pollution incidents by purse seine vessels and more than 200 pollution incidents by longline vessels within the Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZs) of 25 Pacific countries and territories, and in international waters. The report finds that 71% of the reported purse seine pollution incidents related to Waste Dumped Overboard; 16% to Oil Spillages and Leakages; and 13% to Abandoned, Lost, or Dumped Fishing Gear.

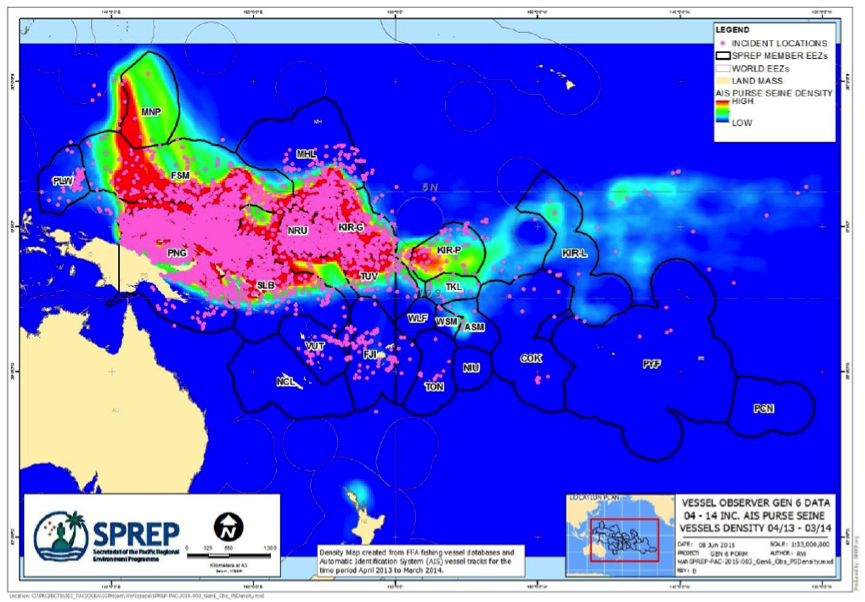

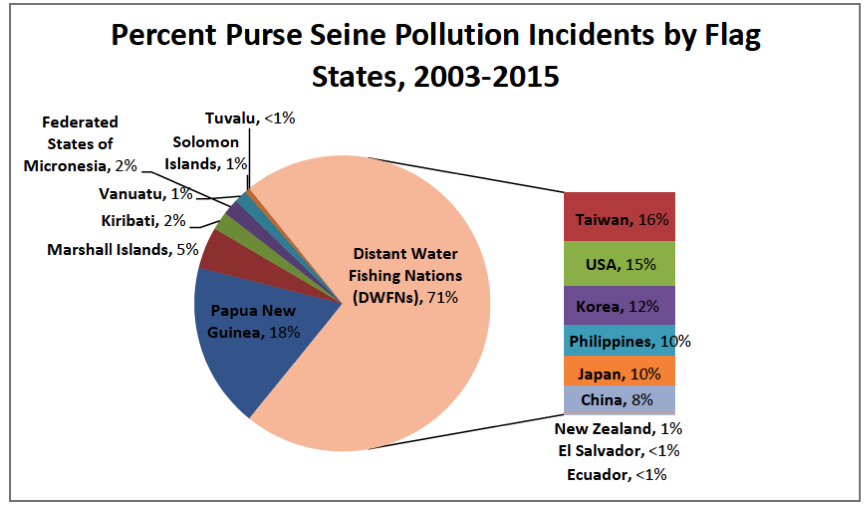

When the category “Waste Dumped” was examined further; Plastics were found to make up the largest portion of total purse seine pollution incidents (37%). Only 4% of the incidents occurred in International Waters, while the rest occurred in the EEZs of Papua New Guinea (44%), Kiribati (13%), the Federated States of Micronesia (12%), Solomon Islands (7%), Marshall Islands (6%), Nauru (6%), and 19 other countries and territories in the Western and Central Pacific Ocean.

While based on limited data, the report finds evidence that pollution from fishing vessels, particularly purse seine vessels, in the Western and Central Pacific Ocean is a serious problem and highlights the need for three initiatives:

Increased monitoring, reporting, and enforcement of pollution violations by all types of fishing vessels, especially longliners, which currently have a very low (5%) mandatoryobserver coverage;

A regional outreach and compliance assistance programme on marine pollution prevention for fishing vessel crews, business operators and managers; and

Improvements in Pacific port waste reception facilities to enable them to receive fishing vessel wastes on shore.

This report provides the first consistent and substantive documented evidence about the nature and extent of ocean-based marine pollution in the Western and Central Pacific Ocean. These incidents were all reported by regional fisheries observers through use of the Secretariat of the Pacific Commission/Pacific Islands Foreign Fisheries Agency (SPC/FFA) Regional Observer Pollution Report Form GEN-6.

The pollution reports are overwhelmingly biased to the purse seine fishery, due to high levels of observer coverage in the fishery, which is mandated by the Western and Central Pacific Fisheries Commission (WCPFC). Prior to 2009, observer coverage for the purse seine fishery was around 5-8%, increased to 20% in 2009, and to 100% required coverage from 2010 to the present (P. Williams, personal communication, March 18, 2015, WCPFC, 2009). By contrast, observer coverage of the approximately 3,000 longline vessels operating in the Western and Central Pacific Ocean is only 5% for the entire fishery as of 2012 (WCPFC, 2014).

There is also likely to be some bias in observer reporting particularly through some observers not reporting MARPOL issues, although the extent of this bias is not yet known.

The report is structured in seven sections.

Section I Introduction

Section II provides a background on ocean-based marine pollution.

Section III describes the history and structure of the SPC/FFA Regional Observer Pollution Report Form GEN-6.

Section IV describes and analyzes the pollution report data, including types, quantities and locations of pollution events.

Section V importantly highlights that pollution incidents by fishing vessels are not isolated to the purse seine fishery, but there is limited information and data for pollution activities by other fisheries, particularly the longline fishery, due to extremely low to no observer coverage in other fisheries. Thus, the pollution data analyzed in this report likely represents only a portion or snapshot of total pollution incidents by fishing vessels throughout the region.

Section VI addresses the need for revisions and updates to the current version of the SPC/FFA Regional Observer Pollution Report Form GEN-6, particularly the need for updates that more clearly communicate revisions to MARPOL Annex V which entered into force in 2013.

Section VII concludes the report and provides recommendations designed for a variety of stakeholders and policymakers to reduce incidents of marine pollution by fishing vessels in the Western and Central Pacific Ocean. The report ends with suggestions for further data analysis and research.

The International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships (MARPOL) is the strongest and most important international regulation to prevent sea-based sources of pollution, including pollution of oil (Annex I) and garbage (Annex V), arising from operational or accidental causes. Despite these regulations, there is limited actual monitoring of MARPOL, and, consequently, little information exists about illegal pollution activities by vessels at sea.

One study in Australia did find that in 1992 and 1993, at least one-third of fishing vessels with onboard observers did not comply with MARPOL regulations prohibiting the dumping of plastics overboard. Of the 14 Pacific island countries who are SPREP members, 11 are Contracting Parties to MARPOL Annexes I/II and V, and therefore have specific responsibilities to implement this important treaty to prevent pollution from ships, particularly in the forms of oil and garbage.

At the fourth SPC/FFA Tuna Fisheries Data Collection Committee in December 2000, SPREP submitted a request for fisheries observers to collect information on marine pollution. This resulted in the creation of the SPC/FFA Regional Observer Pollution Report Form GEN-6. Form GEN-6 was designed by SPREP in partnership with SPC and FFA as a tool to monitor fishing vessel violations to the International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships (MARPOL).

Pollution categories were created based on MARPOL’s Annexes I and V which provide regulations for the prevention of pollution by oil and garbage by ships, respectively. SPC is responsible for maintaining and managing all observer data including the Form GEN-6 data which it started collecting in 2004. In March, 2015 SPREP requested access to the GEN-6 data from SPC and were provided with more than 10 years of data from 2003 through 2015.

Form GEN-6 documents marine pollution incidents by fishing vessels in three categories: Waste Dumped Overboard, Oil Spillages and Leakages, and Abandoned or Lost Fishing Gear. Each category has its respective subcategories, and revisions have occurred to improve reporting over the years, such as the addition of the category Abandoned or Lost Fishing Gear in 2009. Subcategories reported here are from the most current form, revised in March, 2014. Subcategories under Waste Dumped Overboard include: Plastics, Metals, Waste Oil, Chemicals, and General Garbage. Subcategories under Oil Spillages and Leakages include: Vessel Aground/Collision, Vessel at Anchor/Berth, Vessel Underway, Land-based Source and Other. Subcategories under Abandoned or Lost Fishing Gear include Lost during fishing, Abandoned, or Dumped.

The form provides an area to report whether there was information posted on and around the vessel about compliance with the latest revisions to MARPOL, as an indicator of vessel and crew awareness of MARPOL regulations. It also includes a section for ‘Other comments’ where observers can add more details about the pollution event. The reverse side of the form provides notes which clarify definitions and reporting areas. At the bottom of the form it is clearly stated for the observer that under MARPOL regulations “It is illegal for any vessel to discard any form of plastics into the sea at anytime; It is illegal for any vessel to discard any form of oil into the sea at anytime and It is illegal for any vessel to dump any form of rubbish into the sea within 12 nautical miles of the seashore.”

Since recent revisions to MARPOL Annex V entered into force in 2013, dumping of almost all garbage types which were previously allowed beyond the 12 nautical mile zone referenced by this note are now prohibited.

In addition to comments, observers are provided an area on the Form GEN-6 to describe the different types of pollution per category and material (subcategory), as well as to describe quantities. There are no standard categorical options for observers to report quantities of pollution and quantities are reported as written comments by observers, which complicates data analysis.