The high seas are not ungoverned. Almost every country has ratified the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), which, in the words of Tommy Koh, president of UNCLOS in the 1980s, is “a constitution for the oceans”. It sets rules for everything from military activities and territorial disputes (like those in the South China Sea) to shipping, deep-sea mining and fishing. Although it came into force only in 1994, it embodies centuries-old customary laws, including the freedom of the seas, which says the high seas are open to all. UNCLOS took decades to negotiate and is sacrosanct. Even America, which refuses to sign it, abides by its provisions.

But UNCLOS has significant faults. It is weak on conservation and the environment, since most of it was negotiated in the 1970s when these topics were barely considered. It has no powers to enforce or punish. America’s refusal to sign makes the problem worse: although it behaves in accordance with UNCLOS, it is reluctant to push others to do likewise.

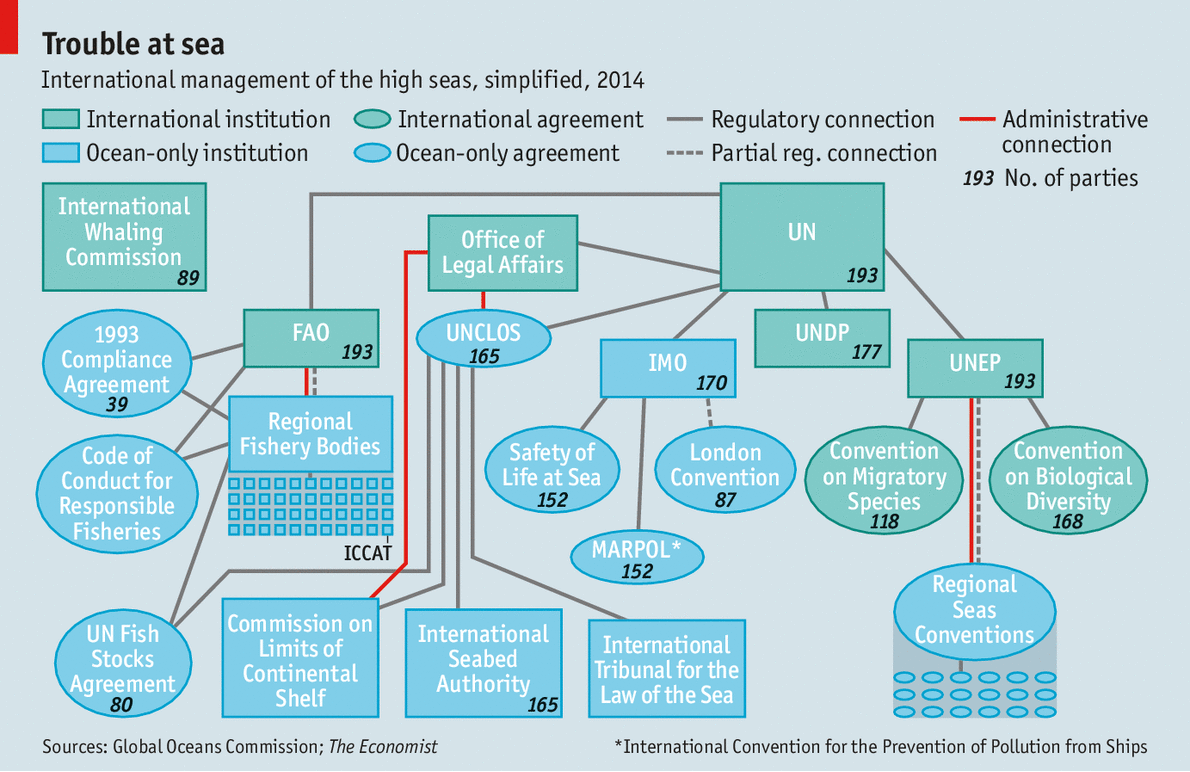

Specialised bodies have been set up to oversee a few parts of the treaty, such as the International Seabed Authority, which regulates mining beneath the high seas. But for the most part UNCLOS relies on member countries and existing organisations for monitoring and enforcement. The result is a baffling tangle of overlapping authorities (see diagram) that is described by the Global Ocean Commission, a new high-level lobby group, as a “co-ordinated catastrophe”.

Individually, some of the institutions work well enough. The International Maritime Organisation, which regulates global shipping, keeps a register of merchant and passenger vessels, which must carry identification numbers. The result is a reasonably law-abiding global industry. It is also responsible for one of the rare success stories of recent decades, the standards applying to routine and accidental discharges of pollution from ships. But even it is flawed. The Institute for Advanced Sustainability Studies, a German think-tank, rates it as the least transparent international organisation. And it is dominated by insiders: contributions, and therefore influence, are weighted by tonnage.